this is a blank placeholder

this is a blank placeholder

How to Learn a Piece

On the Classical Guitar

"Douglas who?"

Douglas Niedt is a successful concert and recording artist and highly respected master classical guitar teacher with 50 years of teaching experience. He is Associate Professor of Music (retired), at the Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City and a Fellow of the Henry W. Bloch School of Management—Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

Doug studied with such diverse masters as Andrés Segovia, Pepe Romero, Christopher Parkening, Narciso Yepes, Oscar Ghiglia, and Jorge Morel. Therefore, Doug provides solutions for you from a variety of perspectives and schools of thought.

He gives accurate, reliable advice that has been tested in performance on the concert stage that will work for you at home.

PURCHASE AN ALL-ACCESS PASS

TO THE VAULT OF CLASSICAL GUITAR TECHNIQUE TIPS

"Hello Mr Niedt,

My name's Gretchen, and I'm so happy I purchased an All-Access Pass to the Vault. I love your awesome technique tips. I'm amazed how much I have improved my playing.

Thank you!"

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR PROVEN STRATEGIES

THAT WILL MAKE YOU A BETTER GUITARIST?

Check out the game-changing tips in my Vault—I promise they will kick your playing up to the next level.

Purchase an All-Access Pass to the Vault.

It's a one-time purchase of only $36!

You receive full access to:

- Over 180 technique tips in The Vault.

- Special arrangements of Christmas music

- Arrangement of the beautiful Celtic song, Skellig

- Comprehensive guide, How to Master the Classical Guitar Tremolo

All that for a one-time payment of only $36. Take me to the page to Purchase an All-Access Pass

HOW TO LEARN A PIECE (SONG)

ON THE CLASSICAL GUITAR, Part 11-B

By Douglas Niedt

Copyright Douglas Niedt. All Rights Reserved.

This article may be reprinted, but please be considerate and give credit to Douglas Niedt.

*Estimated minimum time to read this article, watch the videos, and listen to the audio clips: 55 minutes.

*Estimated minimum time to read the article, watch the videos, listen to the audio clips, and understand the musical examples: 1.5-3 hours.

NOTE: You can click the navigation links on the left (not visible on phones) to review specific topics.

In Part 1, we laid the groundwork for learning a new song:

- We set up our practice space.

- We learned to choose reliable editions of the piece we are going to learn.

- We learned that it is essential to listen to dozens of recordings and watch dozens of videos to hear the big picture as we learn a new piece.

- We learned that it is important to study and analyze our score(s).

- We learned how to make a game plan for practicing our new piece.

- We learned why it is so vital NEVER to practice mistakes and the neuroscience behind it.

- We learned practice strategies to master small elements, including "The 10 Levels of Misery," which ensures we don't practice mistakes.

- We learned where to start practicing in a new piece.

- We learned that it is vital to master small elements first.

- We learned the two most fundamental practice tools—The Feedback Loop and S-L-O-W Practice.

In Part 4, we learned how to use the "Slam on the Brakes" and "STOP—Then Go" practice strategies to:

In Part 5, we learned how to practice with the right hand alone to:

- Apply planting or double-check the precision of your planting technique

- Correct or improve the balance between the melody, bass, and accompaniment

- Apply or improve string damping

- Master passages with difficult string crossings

In Part 6, we learned how to practice with the left hand alone to learn, improve, and master:

- The "lag behind" technique

- How to lift fingers to avoid string squeaks

- Left-hand finger preparation

- Synchronization of left-hand finger movements

In Part 7, we learned more on how to practice with the left hand alone to learn, improve, and master:

- Shifts

- Pre-planting the left-hand fingers

- Collapsing (hyperextending) the tip of the first finger going into and out of a bar chord

- Difficult chord changes without tiring, injuring, or "locking up" the left hand by practicing with light finger pressure

In Part 8, we began learning how to practice with Altered Rhythms. We learned the benefits and six specific strategies:

- How to practice the most common altered rhythms: dotted rhythms

- How to lengthen a particular note within each beat to alter the rhythm

- How to use extended pauses in altered rhythms to reduce tension in the hands

- How to lengthen a particular beat in each measure to alter the rhythm

- How to insert a very long pause (fermata) and play the following notes as grace notes to alter the rhythm

- How to change the accents to alter the rhythm

In Part 9, we concluded our discussion of practicing with Altered Rhythms. We learned:

- How to apply altered rhythms in divisions of 2 to a scale

- How to apply altered rhythms in divisions of 2 to a passage from a piece (not a scale)

- How to apply altered rhythms in divisions of 3 to a scale

- How to apply altered rhythms in divisions of 3 to a passage from a piece (not a scale)

In Part 10, we concluded our discussion of practicing with Altered Rhythms. We learned:

- Four-part harmony, the notation of choral music, and how that applies to the notation of voicing in guitar music

- The multi-dimensionality of music moving vertically and horizontally

- The limitations of guitar notation

- The notation of voices in guitar music

In Part 11-A, we began to learn how to practice the individual voices in a piece to:

HOW TO PRACTICE THE VOICES OF YOUR MUSIC

Part 11-B

In Part 10, we learned how to identify the individual voices in a piece of music. I mentioned that this skill provides many benefits:

- The most obvious benefit is that knowing which notes form the melody will help you practice playing those notes more prominently than those in subordinate voices. Usually, making the melody prominent is key to making a piece sound its best.

- If we can identify the voices in our music, we can use some advanced practice strategies in which we practice the voices separately to improve several elements of our playing.

- We can learn which notes form the accompaniment and practice it independently. That way, we can easily hear any flaws in our playing of the accompaniment and fix them. Practicing the accompaniment alone also increases our awareness of what the accompaniment sounds like by itself.

- If you know which voice is which, you can adjust the relative balance between two or more parts with great precision.

- Separating the music into its component voices allows you to see the independent rhythms of each part so that you hold the notes for their correct duration.

- Practicing the individual voices of a passage shines a spotlight on flaws in fingering and execution.

- Practicing the individual voices helps us choose whether to play a voice as a pure line (only one note ringing at a given moment) or allow notes to ring together.

- We can improve the tone quality of a voice.

- We can improve the clarity of the voices (eliminate buzzes and muted notes).

- In contrapuntal music, we can learn to hear the individual voices and how they interact. Then, we can apply practice tools to make those interactions crystal clear.

- An awareness of the voices of the music enables you to hear and appreciate the intricacies, uniqueness, creativity, and wonder of the composer or arranger's work. That awareness will permeate your playing, and your listeners will also sense and hear it.

- You can go even further by finding hidden or implied voices in both contrapuntal and non-contrapuntal music. When you differentiate these voices, you will give the piece the lifelike multi-dimensionality the composer intends it to have, rather than a dull, colorless, one-dimensional sound.

I also explained that practicing the individual voices of a song, section, or measure is a powerful practice tool you can use to learn a new piece or improve an old one. But it is complicated to use.

In Part 11-A, I explained how to use it to achieve benefits #1 through 4.

Here, in Part 11-B, I will explain how we can use it to achieve benefits #5 through 9.

I should also point out once again that finding the voices and knowing which notes belong to which voice is ALWAYS USEFUL. However, practicing individual voices is not always convenient. Sometimes figuring out how to play and practice an individual voice is so complex or time-consuming that it isn't worth the trouble. But in many instances, it is the best way to diagnose and fix problem passages.

4. Separate the music into its component voices so that you can examine the independent rhythms of each part and hold the notes for their correct duration.

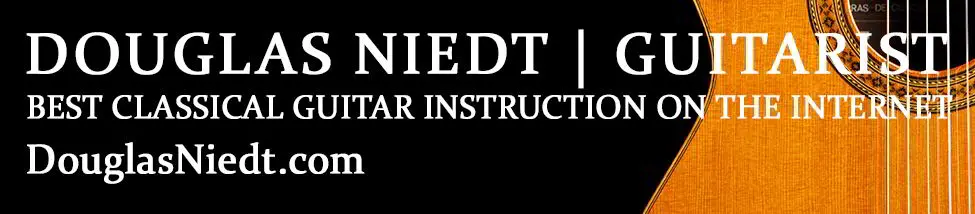

Sometimes, so much is going on in a passage that we don't notice we are cutting notes short that should keep ringing. For example, the last four measures of Andante from Book 2 of Twenty-Four Very Easy Exercises, Op. 35 No. 13 (Study No. 2 in Segovia's Twenty Studies by Fernando Sor), are very challenging. Example #272:

With the bar chords and intricate formations, it is easy to accidentally lift the low F in measure #30 and the low G in measure 31 early. However, if we look at the notation of the voices, we clearly see they are both half notes. Therefore, if we practice the voices separately, as I described in Part 11-A, we can be sure we are holding the notes for their full value.

As I explained before, we should practice each voice separately and in pairs for the maximum benefit. But if we only want to solve this one problem, we only need to practice the bass voice. We will fret all the notes but pluck only the basses to hear if they sustain for their full value. Example #273:

You can apply this same approach to any piece in multiple voices where you want to be sure you are holding all the notes their correct value.

Watch me demonstrate this very effective practice method (plus the "TremoloMute Bridge Dampening System") in Video #50.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right:

Video #50: Fret All the Notes but Pluck the Bass Voice Only, Study No. 3 (Fernando Sor), m29-32

5. Practice the Individual Voices to Learn to Eliminate Choppy Playing and Detect Bad Fingering

Find and Fix Bad Fingerings

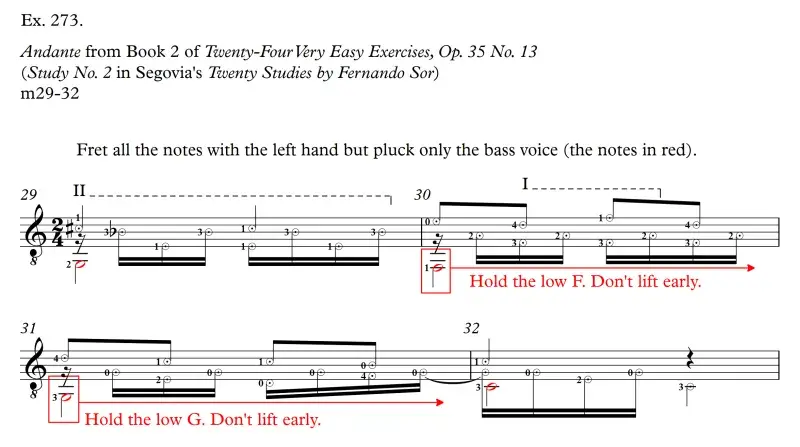

While preparing to write this article, I looked for pieces I could use as examples. I thought about using Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring by J.S. Bach, a piece I have played for many years. Example #274:

I started reviewing the passage by fretting all the notes but plucked only the notes in the alto voice (the blue notes). Example #275:

And lo and behold, I found a choppy spot in the alto voice of measure #3 due to a bad fingering! I couldn't believe it. Using the 3rd finger to play two notes in a row in the alto voice doomed it to be choppy. Before now, apparently, I had never played the individual voices of this section, so I never caught the problem. It isn't terrible since it is buried in the middle voice, but still, that's a rookie error!

Watch me demonstrate the problem in Video #51.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right:

Video #51: Fret All the Notes but Pluck the Alto Voice Only, Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring (J.S. Bach), m1-4

Next, I played the passage again, this time fretting all the notes but only plucking the notes in the soprano voice (the red notes). Example #276:

Oh no! I was chopping the melody going from measures 3-4. Again, I was using a bad fingering. I was leaping the 2nd finger from a melody note on the 2nd string to a bass note on the 6th string. How I missed this for so many years is hard to fathom. The lesson I learned is that knowing where the voices are and which note belongs to which voice is essential, but you must also HEAR AND LISTEN TO the voices when you practice!

Watch me demonstrate and explain the bad fingering in Video #52.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right:

Video #52: Bad Fingering in the Soprano Voice, Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring (J.S. Bach), m1-4

Fortunately, it was easy to change the fingering to eliminate the choppiness and make everything legato in both the soprano and the alto. Example #277:

Now, neither finger leaps from string to string, making everything connected.

Watch me explain and demonstrate the solution in Video #53.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right:

Video #53: The Fingering Solutions, Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring (J.S. Bach), m1-4

Good Fingerings but Find and Correct Bad Playing

Practicing each voice of your piece by itself will help you find bad fingerings such as the ones I used in Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring. But sometimes, you can't blame bad fingerings. Many times the problem is your own bad playing!

Let's look at the opening four measures of Un Dia de Noviembre by Leo Brouwer. Notice that the bass voice consists of dotted half notes that should connect to one another. Example #278:

If you fret everything but pluck only the bass voice, you may discover that you lift the G, F, or both early. Example #279:

Practicing the bass voice alone allows you to train the fingers not to lift early to keep the bass voice legato. You could also use the "TremoloMute Bridge Dampening System."

Watch me demonstrate how to connect the bass notes in Video #54.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right:

Video #54: Connecting the Bass Notes, Un Dia de Noviembre (Leo Brouwer), m1-4

But you may notice that the conventional fingering from measures 3 to 4 requires the 1st finger to leap from the 6th string bass note to the 2nd-string melody note. Example #280:

Therefore, with that fingering, it is not possible to make a perfect legato connection in the bass line from measures 3-4.

But with a bit of fingering trickery (using the technique of finger substitution), we can make a perfect connection. Example #281:

It may be more trouble than it's worth, but it is doable.

When you practice the voices of your music individually, it shines a spotlight on flaws in your fingering and playing. Then, you can use the tool to find a better fingering or fix the flaws in your execution. Therefore, use this practice tool whenever possible.

Watch me demonstrate the solution and finger substitution technique in Video #55.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right:

Video #55: Fingering Solutions and Finger Substitution, Un Dia de Noviembre (Leo Brouwer), m1-4

6. Practice the individual voices to help you choose whether to play a voice as a pure line (only one note ringing at a given moment) or to allow notes to ring together.

Playing the Soprano Voice as a Pure Line

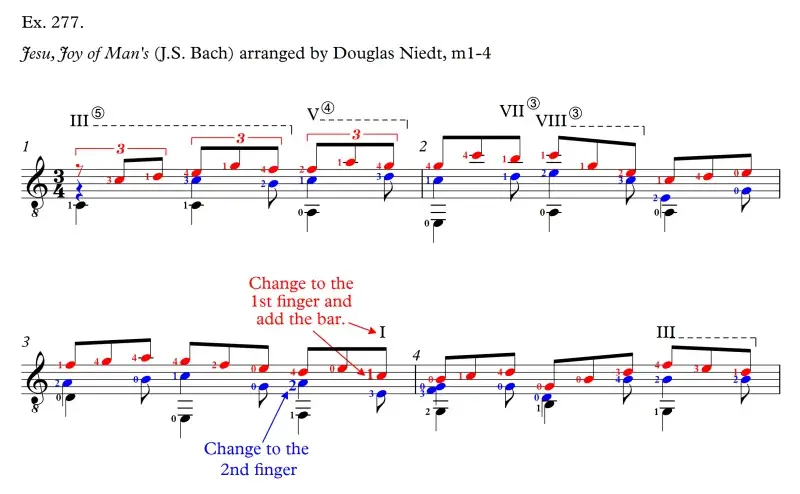

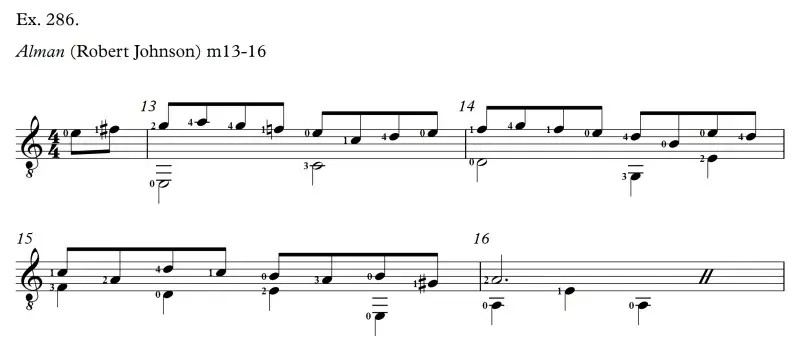

Here are measures 13-16 from Alman by English lutenist Robert Johnson (1583-1633) arranged for the guitar. Example #282:

Let's extract the upper voice. Example #283:

On paper, it looks like a simple melody LINE. When we use the word line, it usually implies playing a passage so that only one note rings at any given moment. If we finger the soprano voice like this, that is how it sounds. Example #284:

However, we could also finger it so that some of the notes ring. If we take it to the extreme, we can finger it as a campanella passage like this. Example #285:

However, if we play the melody with the bass line, our fingering choices are fewer. For instance, here is a conventional fingering for the passage. Example #286:

Let's fret both voices but pluck only the soprano voice (melody). Example #287:

You can hear some of the open strings ringing over into adjacent notes. They form intervals (often dissonant) with the notes that follow, producing a nebulous texture. The faster the passage, the more unclear it will be. That is not a pure line. But, to some players, that is acceptable.

However, if we want to produce a pure melody line in this passage more in keeping with the contrapuntal style of the period, we will need to employ string damping, perhaps like this. Again, if you aren't familiar with the intricacies of string damping, consult my four-part series, beginning with String Damping—Part 1. Example #288:

Now it sounds like a line. We only hear one note ringing at any given moment.

Playing the Bass Voice as a Pure Line

All of these considerations also apply to the bass line in almost any passage, but even more so. The sound becomes very muddy when bass notes ring together, especially if they form dissonant intervals. As the speed of the passage increases, the muddiness becomes worse.

In our Alman, without string damping, the bass notes will ring over into other notes like this. Example #289:

But we can clean up the bass line with string damping. Example #290:

If I apply the damping techniques marked in the music to the bass voice, it will sound like a line.

To play both voices of this passage as pure lines requires quite a bit of string damping, which is not unusual for contrapuntal music of the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Here are all the string damps for both voices. Example #291:

Watch me play the passage and explain the string damping as I play both voices as pure lines in Video #56.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right:

Video #56: Damping Technique to Produce Clean Lines, Alman (Robert Johnson), m13-16

You Can Play a Voice as a Pure Line or Not—The Choice is Yours

Whether you choose to play a voice as a pure line or not is up to you. By practicing the voice by itself and adjusting the fingering and string damping, you can make it sound however you want—as a pure line, a campanella, or anything in between. Campanella fingerings are a special effect. Pure lines are usually best for contrapuntal music of the Renaissance and Baroque periods. However, from the classical period onward, pure lines sound best in some passages and semi-pure lines best in others. By semi-pure, I mean allowing the guitar's open strings to ring against adjacent notes or holding down notes together as intervals or chords, especially if they are consonant. Allowing notes to ring adds resonance but at the expense of clarity.

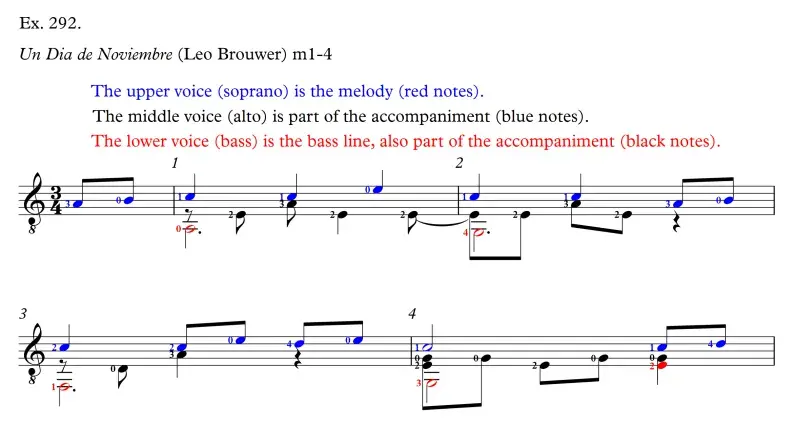

Let's look again, this time at the melody (the soprano voice) of the first four measures of Un Dia de Noviembre. Example #292:

We can choose to allow the open strings to ring into adjacent notes and hold melody notes together to form intervals. This approach adds resonance. The ringing notes produce several dissonances, but they are certainly not foreign to the style of this 20th-century piece. Example #293:

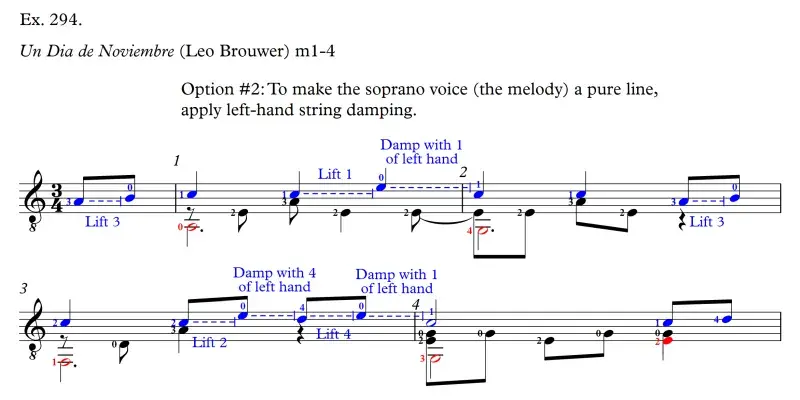

Or, we can lift fingers and damp notes to play the melody as a pure line. Example #294:

As with the Robert Johnson Alman, we can test both options by fretting all the notes but only plucking the soprano voice (melody). Then, we can pluck ALL of the notes of both voices using both options to hear how it all fits together.

In this case, I think both sound good. Of course, a clean, clear melody is always desirable, but the added resonance of allowing the notes to ring is also attractive. But, once again, it is your choice how you want the passage to sound.

Practicing the individual voices will help you make a choice. Practicing the individual voices enables you to hear all the details more clearly and will help you master the proper techniques to make it happen.

7. Practice the individual voices to improve your tone quality

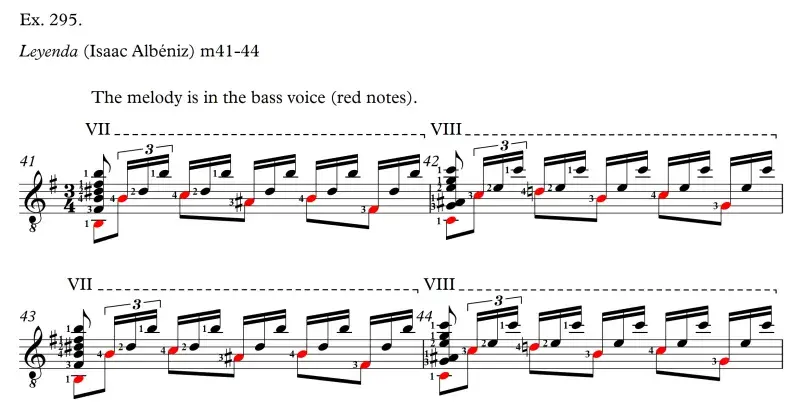

When we play complex pieces in two or more voices, there is so much going on that it can be hard to focus on the tone quality of a particular voice. For instance, in Leyenda by Isaac Albéniz, we have this blazing passage where we play the melody in the bass voice with the thumb. Example #295:

For most players, the first choice for positioning the right hand is a normal position. The normal position is comfortable for executing the fast arpeggios. But the normal position results in the thumb plucking the bass strings from behind or even slightly underneath the string. The result is a somewhat thin sound. We don't want thin. In some interpretations, these measures are the climax of the work. We are playing this phrase at full volume. To produce a thick, robust tone, we need to arch the wrist so that the thumb plays on top of the string, pushing the string down into the soundboard, akin to a thumb rest stroke.

Watch me demonstrate the two hand positions in Video #57.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right:

Video #57: Two Hand Positions for Playing a Bass Line with the Thumb, Leyenda (Isaac Albéniz), m41-44

If we fret all the notes but pluck just the bass voice (the melody), we can easily hear how our hand position affects the tone. Example #296:

Practicing an individual voice is a great tool to use to evaluate the tone quality of any piece you play or are learning. You can improve the tone quality of the melody, the bass, or any inner voice.

Watch me apply this practice technique to evaluate the tone quality of the melody of Leyenda in Video #58.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right:

Video #58: Fret all the Notes but Pluck the Bass Line to Evaluate Tone Quality, Leyenda (Isaac Albéniz), m41-44

8. Practice the individual voices to improve the clarity of the notes within the voice (eliminate buzzes and muted notes)

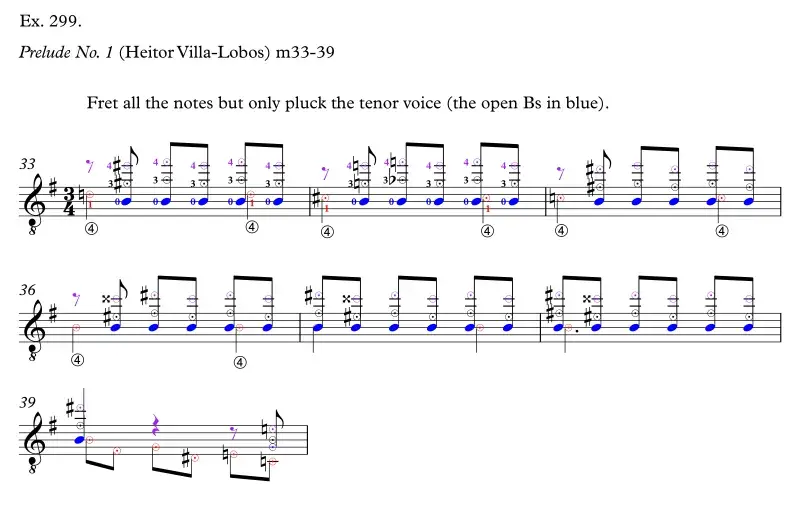

In Prelude No. 1 by Heitor Villa-Lobos, we have a passage that is notoriously difficult to play without accidentally damping the open Bs or buzzing/muting the notes on the 1st and 3rd strings. Example #297:

To diagnose the problems and fix them, the most efficient way to practice is to fret all the notes but pluck one voice at a time. Although Villa-Lobos notated the accompaniment as one voice with the note stems pointing upward, consider each note of each chord as a separate voice to practice. In other words, the notes on the 1st string are the soprano voice, the notes on the 3rd string are the alto voice, and the open Bs are the tenor voice. Example #298:

Now, we can go through the steps of rehearsing each voice by itself. Let's start with the one that is most challenging for most players. If you can get this one clear, the other voices will often be okay, and the passage will be fixed! Example #299:

Try playing the passage again, plucking all four voices. If it sounds good, you are done. If not, try fretting all the notes but pluck only the soprano voice (the notes in purple). Example #300:

Try playing the passage again, plucking all four voices. If it sounds good, you are done. If not, try fretting all the notes but pluck only the alto voice (the notes on the 3rd string in black). Example #301:

Finally, try playing the passage again, plucking all four voices. If it sounds good, you are done. If not, try fretting all the notes but pluck only the bass (melody) voice (the notes on the 4th string in red). Example #301b:

Try playing all four voices of the passage again. You should have found the problem voice and fixed it by now. If not, go back through the steps to re-diagnose which notes in which voices are not clear.

Use this process to find buzzes and muted notes on any passage that you can divide into separate voices. Practice each voice separately to narrow the search for the bad notes and efficiently apply fixes to make the notes clear again.

Watch me demonstrate this process in Video #59.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right:

Video #59: The Process to Improve the Clarity of Individual Voices, Prelude No. 1 (Heitor Villa-Lobos), m41-44

TO BE CONTINUED

DOWNLOADS

1. Download a PDF of the article with links to the videos and audio clips. Depending on your browser, it will download the PDF (but not open it), open it in a separate tab in your browser (you can save it from there), or open it immediately in your PDF app.

Download the PDF: HOW TO LEARN A PIECE (SONG) ON THE CLASSICAL GUITAR Part 11-B (with links to the videos and audio clips)

2. Download the videos. Click on the video link. After the Vimeo video review page opens, click on the down arrow in the upper right corner. You will be given a choice of several different resolutions/qualities/file sizes to download.

Video 50: Fret All the Notes but Pluck the Bass Voice Only, Study No. 3 (Fernando Sor), m29-32

Video 51: Bad Fingering in the Soprano Voice, Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring (J.S. Bach), m1-4

Video 52: The Fingering Solutions, Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring (J.S. Bach), m1-4

Video 53: The Fingering Solutions, Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring (J.S. Bach), m1-4

Video 54: Connecting the Bass Notes, Un Dia de Noviembre (Leo Brouwer), m1-4

Video 55: Fingering Solutions and Finger Substitution, Un Dia de Noviembre (Leo Brouwer), m1-4

Video 56: Damping Technique to Produce Clean Lines, Alman (Robert Johnson), m13-16

Video 57: Two Hand Positions for Playing a Bass Line with the Thumb, Leyenda (Isaac Albéniz), m41-44

Video 58: Fret all the Notes but Pluck the Bass Line to Evaluate Tone Quality, Leyenda (Isaac Albéniz), m41-44

Video 59: The Process to Improve the Clarity of Individual Voices, Prelude No. 1 (Heitor Villa-Lobos), m41-44