this is a blank placeholder

How to Learn a Piece

On the Classical Guitar

"Douglas who?"

Douglas Niedt is a successful concert and recording artist and highly respected master classical guitar teacher with 50 years of teaching experience. He is Associate Professor of Music (retired), at the Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City and a Fellow of the Henry W. Bloch School of Management—Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

Doug studied with such diverse masters as Andrés Segovia, Pepe Romero, Christopher Parkening, Narciso Yepes, Oscar Ghiglia, and Jorge Morel. Therefore, Doug provides solutions for you from a variety of perspectives and schools of thought.

He gives accurate, reliable advice that has been tested in performance on the concert stage that will work for you at home.

PURCHASE AN ALL-ACCESS PASS

TO THE VAULT OF CLASSICAL GUITAR TECHNIQUE TIPS

"Hello Mr Niedt,

My name's Gretchen, and I'm so happy I purchased an All-Access Pass to the Vault. I love your awesome technique tips. I'm amazed how much I have improved my playing.

Thank you!"

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR PROVEN STRATEGIES

THAT WILL MAKE YOU A BETTER GUITARIST?

Check out the game-changing tips in my Vault—I promise they will kick your playing up to the next level.

Purchase an All-Access Pass to the Vault.

It's a one-time purchase of only $36!

You receive full access to:

- Over 180 technique tips in The Vault.

- Special arrangements of Christmas music

- Arrangement of the beautiful Celtic song, Skellig

- Comprehensive guide, How to Master the Classical Guitar Tremolo

All that for a one-time payment of only $36.

Take me to the page to Purchase an All-Access Pass

Everything on the website carries a no-risk, money-back guarantee.

HOW TO LEARN A PIECE (SONG)

ON THE CLASSICAL GUITAR, Part 8

By Douglas Niedt

Copyright Douglas Niedt. All Rights Reserved.

This article may be reprinted, but please be considerate and give credit to Douglas Niedt.

*Estimated minimum time to read this article and listen to the audio clips: 45 minutes.

*Estimated minimum time to read the article, listen to the audio clips, and play through the musical examples: 2-4 hours.

NOTE: You can click the navigation links on the left (not visible on phones) to review specific topics or videos.

In Part 1, we laid the groundwork for learning a new song:

- We set up our practice space.

- We learned to choose reliable editions of the piece we are going to learn.

- We learned that it is essential to listen to dozens of recordings and watch dozens of videos to hear the big picture as we learn a new piece.

- We learned that it is important to study and analyze our score(s).

- We learned how to make a game plan for practicing our new piece.

- We learned why it is so vital NEVER to practice mistakes and the neuroscience behind it.

- We learned practice strategies to master small elements, including "The 10 Levels of Misery," which ensures we don't practice mistakes.

- We learned where to start practicing in a new piece.

- We learned that it is vital to master small elements first.

- We learned the two most fundamental practice tools—The Feedback Loop and S-L-O-W Practice.

In Part 4, we learned how to use the "Slam on the Brakes" and "STOP—Then Go" practice strategies to:

In Part 5, we learned how to practice with the right hand alone to:

- Apply planting or double-check the precision of your planting technique

- Correct or improve the balance between the melody, bass, and accompaniment

- Apply or improve string damping

- Master passages with difficult string crossings

In Part 6, we learned how to practice with the left hand alone to learn, improve, and master:

- The "lag behind" technique

- How to lift fingers to avoid string squeaks

- Left-hand finger preparation

- Synchronization of left-hand finger movements

In Part 7, we learned more on how to practice with the left hand alone to learn, improve, and master:

PRACTICING IN ALTERED RHYTHMS, Part 1

*Notes: (1.) A few years ago, I wrote a Technique Tip, Practicing in Altered Rhythms. The discussion here expands considerably on that tip. (2.) Some teachers call "Practicing in Altered Rhythms" "practicing rhythms" or "practicing dotted rhythms." However, "practicing dotted rhythms" is only a small subset of the overall topic.

#######

Do you ever reach a point in learning a piece where it just doesn’t seem to get any better? Do you find that you still make mistakes in the same places or have difficulty with the same chord changes or scale passages? Or especially, do you find that even when you play a piece you have been playing for years that the same passages still trip you up?

I learned how to overcome those difficulties from pianist Samuel Sanders, one of the most respected accompanists of the twentieth century. Sanders was Itzhak Perlman’s chief accompanist from 1966-1999 and accompanist to Pinchas Zukerman, Paula Robison, Yo-Yo Ma, Joshua Bell, Mstislav Rostropovich, and many others. One of his crucial practice routines was to practice using altered rhythms.

The Benefits of Practicing Altered Rhythms

Build Good Muscle Memory and Dismantle Bad Muscle Memory to Construct New Neural Pathways

When we change the rhythm of a passage, we come to know it from a variety of different angles. As a result, the brain sees the patterns differently with each rhythmical variation. Therefore, it is easier to play faster, evenly, and more accurately when we return to the original.

Practicing altered rhythms seems to break up muscle memory; especially old, entrenched muscle memory that produces the same mistakes day after day, month after month, and year after year. On a piece you have been playing a long time, the pauses will break the momentum of old, faulty muscle memory that you can now replace with the correct movements. Remember our discussion on the importance of myelinating the correct neural pathways?

Improve Finger Preparation

The long notes in an altered rhythm help train the fingers on both hands to prepare for the following fast note or notes. A pause allows the fingers on both hands to hover above the next note or string, reinforcing the muscle memory needed to play that note.

Learn to Make Fast Finger Movements

Practicing with altered rhythms sharpens the reflexes. When you practice with altered rhythms, you prolong some notes but speed up other notes or groups of notes into a reflex, tricking your brain and body into playing fast without feeling like you are increasing the overall tempo. In other words, you may not have the skill to play all the notes in a scale fast, but an altered rhythm makes it possible for you to play some of the notes and the transitions from note to note very fast, almost as a reflex. If you change the rhythm again, you will learn to play other groups of notes and the transitions very fast. After practicing several rhythms, you will soon have the ability to play ALL the notes and transitions fast, and voila, you have a complete scale at a speed you thought you could never attain.

By treating groups of notes as reflexes, practicing in altered rhythms in some instances can improve the synchronization of the two hands.

Reduce Tension in the Hands

When we play fast notes, we use an explosion of energy. Over a few measures, tension can build in the hands and produce mistakes or slow the hands down. We can use the long notes in our altered rhythms as an opportunity to train the hands and fingers to release that energy, so they learn to stay relaxed through an entire passage.

Improve Slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs)

We even apply the altered rhythms to any slurs in the passage. Practicing the altered rhythms with the slurs will help improve the clarity, rhythmic precision, and strength of your hammer-ons and pull-offs.

Correct Problems with Right-Hand Fingering

Accenting the notes in different patterns helps diagnose and correct problems with alternating the right-hand fingers or not using the intended right-hand fingering. Accenting a note increases your awareness of which right-hand finger is plucking that note. You will often catch yourself using an unintended finger, especially at a string cross or after a slur.

Maintain Focus and Engagement

Practicing with altered rhythms also keeps the brain engaged. For example, if you repeat a passage ten times, it is hard to maintain your focus 100% of the time. But if you play the passage once or twice in the original rhythm, change to an altered rhythm, go back to the original, change to a second altered rhythm, go back to the original, etc., your brain and hands must constantly readjust and think about what is happening. The procedure also forces you to listen more closely to each repetition.

Questions Before We Begin?

In what situations does altered rhythm practice work best?

Altered rhythm practice works best on passages in steady 16th or 32nd notes. However, some of the fundamental alterations will even work on slower passages. It does not work on passages that are already in mixed rhythms.

I find that using altered rhythm practice works wonders both on old and new pieces

Whether your focus is on speed or accuracy, I recommend practicing the altered versions at slow and fast tempos. Both slow and fast practice is beneficial for most passages.

When Can I Start Practicing a Passage in Altered Rhythms?

Be sure you can play a passage as written at a slow tempo before practicing it in altered rhythms.

Does Practicing with Altered Rhythms Work for Everyone?

I find that when a guitarist uses it wisely and on suitable passages, it works amazingly well, but it is not a cure-all for every technical problem. And, like everything else in music, not all teachers agree that the strategy is beneficial. Some oppose it, but it is a standard practice routine in most conservatories worldwide.

How is Practicing in Altered Rhythms Different from the "STOP—Then Go" Practice Tool?

In Part 4, we learned about the STOP—Then Go" practice strategy. It is a form of practicing in altered rhythms. The difference is that in "STOP—Then Go," the pauses are an indefinite or random duration. They are fermatas. In altered rhythm practice, usually, the pauses are precise rhythmic values.

QUICK TIP

Except for the simplest altered rhythms, I find it easier to practice a passage if I write down the passage with each altered rhythm.

- You don't need an expensive notation program to do this. Instead, write the passage out with pencil and paper, the old-fashioned quick and easy way!

- Plus, if you write the passages out on paper, you don't need to figure out and write in the meter (3/4, 9/4, 13/8, etc.) as I did in this technique tip. Instead, write the rhythmic values only (quarter notes, 8th notes, dotted 8th notes, 16th notes, etc.).

- Include any slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs)

- Finally, be sure to write in the left AND RIGHT-HAND fingerings so that you practice them correctly.

TRY SOME OF THESE OUT!

- Play or listen to some of the examples below to understand the process.

- Then, apply some of these patterns to a passage from a piece you already know or are learning.

- When you play the altered rhythm patterns, be sure you are playing the notes cleanly and the rhythms precisely.

- Play the original rhythm first. Then practice an altered rhythm for a few minutes. Then return to the original rhythm. You can alternate back and forth randomly. Experiment with how much to practice the altered rhythm and how much to play the original rhythm.

- Use other tools in conjunction with altered rhythms. For instance, practicing with the right hand alone can be very helpful. I highly recommend using a metronome occasionally. It will help you to judge the precision of your rhythms.

- If you have trouble playing an altered rhythm precisely, break down the passage into smaller units. Then, put it back together.

The Most Common Altered Rhythms: Dotted Rhythms

If your practice time is limited, practice the most commonly-used altered rhythms: the long-short and short-long dotted rhythms. Example #128:

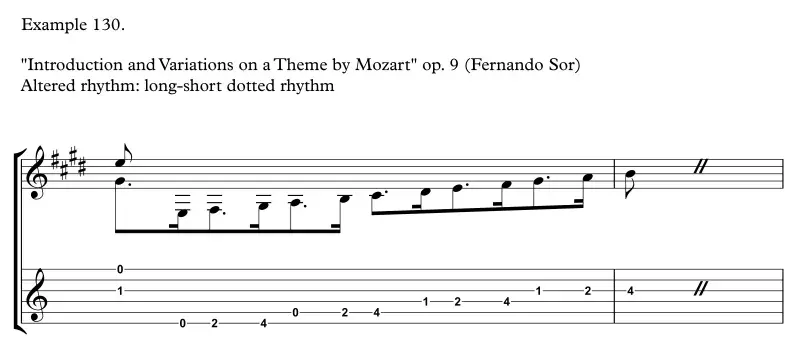

These two dotted rhythms are suitable for the widest variety of passages. We can easily use them on scales. For example, we have this fast scale at the end of Fernando Sor's Introduction and Variations on a Theme by Mozart op. 9. Note that you might use a different left and right-hand fingering than mine. That doesn't matter. The practice procedure will be the same. Here is the passage with the original rhythms. Example #129:

Using the long-short dotted rhythm, we will practice it like this. Example #130:

On the other hand, using the short-long dotted rhythm looks like this. Example #131:

NOTE: Usually, we can change a passage into a dotted rhythm by ear. However, a tricky passage may occasionally require us to rewrite it in the dotted rhythm. If the passage confuses you, take the time to rewrite it.

Also, some teachers recommend this procedure to practice this pair of dotted rhythms:

- Practice the passage with the original rhythm at the fastest speed that you can play with no mistakes.

- At a slower speed, practice the passage with the first dotted rhythm until you master it.

- Go directly to the second dotted rhythm. Again, at the slower speed, practice until you master it.

- End by practicing the original rhythm.

Important: Sometimes, the precision of the dotted rhythm at a string cross, intricate fingering, or shift may not match the rest of the dotted rhythms. You might need to practice these smaller groups of notes on their own to make every dotted rhythm the same. Also, double-dotting the rhythms is often very effective.

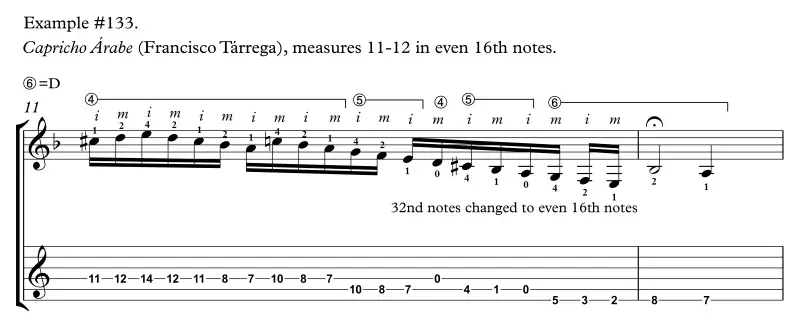

Or, here is one of the fast scales in Capricho Árabe by Francisco Tárrega. Example #132:

On this and similar passages, sometimes the notes may not be the same duration. Here, we have a mix of 16th and 32nd notes. Sometimes we can even out the note values for practice efficiency. Here, I would change the 32nd notes to 16th notes. I would also eliminate the grace note slide. Example #133:

Now, we can apply altered rhythms to the scale. And, once again, your fingering may differ from mine. But it doesn't matter. The practice procedure will be the same. Here is the passage in the dotted long-short rhythm. Example #134:

And here is the scale in the dotted short-long rhythm. Example #135:

Important: Sometimes, the precision of the dotted rhythm at a string cross, intricate fingering, or shift may not match the rest of the dotted rhythms. You might need to practice these smaller groups of notes on their own to make every dotted rhythm the same. Also, double-dotting the rhythms is very effective.

Oftentimes, practicing dotted rhythms will help clean or tighten up a shift (make it more connected). For example, when you apply the long-short dotted rhythm to the Capricho Árabe scale, you might suddenly notice sloppiness on the shift going from the last note of measure 11 to the first note of measure 12. It tells you this spot needs extra practice. Similarly, practicing the short-long dotted rhythm will most likely uncover a lack of control of the shift in measure 11 from the 5th to the 6th note (4th-string C# to the 4th-string Bb). Practicing the dotted rhythms points out which shifts are weak and makes you think to move more quickly and decisively to connect the notes.

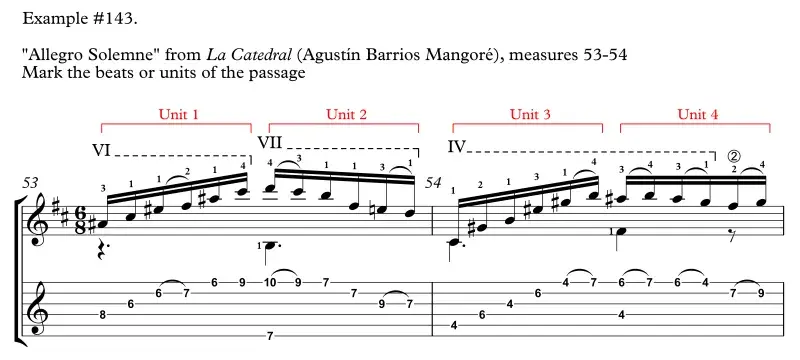

We can even apply these two basic dotted rhythms to a complex passage such as this one from the "Allegro Solemne" of La Catedral by Agustín Barrios Mangoré. Again, some guitarists can change a passage such as this into a dotted rhythm by ear. However, some pieces may occasionally require us to rewrite the passage in the dotted rhythm. If the passage confuses you, take the time to rewrite it.

Here is the music in the original rhythms. The fingerings and slurs are mine. Other guitarists may use different fingerings or add or take away slurs. It doesn't matter. The practice procedure is the same. Example #136:

If we apply the long-short dotted rhythm to the passage, it will look like this. Example #137:

Notice that we apply the dotted rhythm even to the slurs—the hammer-ons and pull-offs. Practicing the altered rhythms with the slurs will help improve the clarity, rhythmic precision, and strength of your hammer-ons and pull-offs.

Now, if we apply the short-long dotted rhythm to the passage, it will look like this. Example #138:

Important: Sometimes, the precision of the dotted rhythm containing a string cross, slur, intricate fingering, or shift may not match the rest of the dotted rhythms. You might need to practice these smaller groups of notes on their own to make every dotted rhythm the same.

We can also apply these two basic dotted rhythms to passages containing even 8th or 16th notes in very easy pieces. We can also apply them to intermediate pieces such as Lágrima by Francisco Tárrega. We could actually practice ALL of Lágrima in dotted rhythms, not just a passage or two.

2. Lengthen a Particular Note Within Each Beat to Alter the Rhythms

Once again, in Part 4, we learned about the STOP—Then Go" practice strategy where the pauses were a random duration. However, in the altered rhythm practice I describe here, the pauses are precise rhythmic values.

Let's return to our scale from Fernando Sor's Introduction and Variations on a Theme by Mozart op. 9. First, we mark the beats or, in this case, the 8th-note units of the scale. Example #139:

We can lengthen each beat's or unit's 1st, 2nd, or 3rd note. Here we lengthen the first note of each unit. Example #140:

Next, we can lengthen the second note of each unit. Example #141:

Finally, we can lengthen the third note of each unit. Example #142:

NOTE: Some players may be able to alter these rhythms by ear. For many, it won't be very clear. If that's the case, take the time to rewrite the passage on a separate piece of paper.

Also, some teachers recommend this procedure:

- Practice the passage with the original rhythm at the fastest speed that you can play with no mistakes.

- At a slower speed, practice the passage with the first altered rhythm until you master it.

- Go directly to the second altered rhythm. Again, at the slower speed, practice until you master it. Then, proceed through any additional altered rhythms.

- End by practicing the original rhythm.

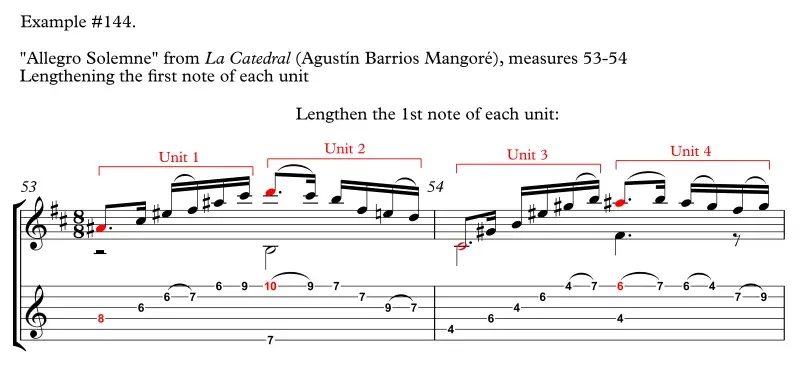

We can apply the same practice strategy to a piece, such as our passage from La Catedral. Again, we mark the beats of units of the passage. Example #143:

Then, we can proceed to lengthen each note of the units. We can lengthen the first note of each unit. Example #144:

We can lengthen the second note of each unit. Example #145:

We can lengthen the third note of each unit. Example #146:

We can lengthen the fourth note of each unit. Example #147:

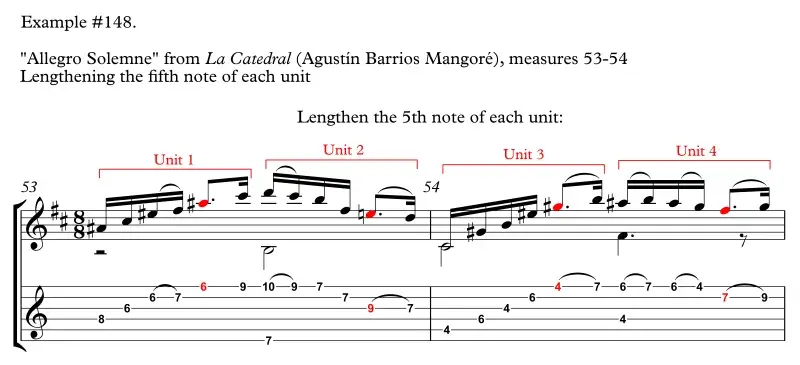

We can lengthen the fifth note of each unit. Example #148:

Finally, we can lengthen the sixth note of each unit. Example #149:

And, of course, you can practice as many or few of these altered rhythms as you want. I find that focusing on the most counterintuitive rhythms is the most helpful in improving a passage.

And again, you can try this procedure:

- Practice the passage with the original rhythm at the fastest speed that you can play with no mistakes.

- At a slower speed, practice the passage with the first altered rhythm until you master it.

- Go directly to the second altered rhythm. Again, at the slower speed, practice until you master it. Then, proceed through any additional altered rhythms.

- End by practicing the original rhythm.

Important: Sometimes, the precision of these rhythms may suffer if the passage contains string crosses, slurs, intricate fingerings, challenging bars, or shifts. You might need to practice smaller groups of notes on their own to maintain precise rhythms.

And once again, if you can't picture or hear these altered rhythms in your head, write them out as exercises on a separate sheet of paper.

3. Use Extended Pauses in Your Altered Rhythm Practice to Reduce Tension in the Hands

When we play fast notes, we use an explosion of energy. Over a few measures, tension can build in the hands and produce mistakes or slow the hands down. We can use the long notes in our altered rhythms as an opportunity to train the hands and fingers to release that energy, so they learn to stay relaxed. If we extend the length of the long notes, we can give the hands extra time to dispel their tension. Upon arrival on each long note, we can command the muscles of the arms, hands, and fingers to loosen to maintain an overall state of effortless playing. As piano pedagogue Graham Fitch describes it, instead of a constant, unrelenting stream of fast notes, in a sense, we are introducing hills and valleys into a previously flat landscape.

Let's return to the scale from Fernando Sor's Introduction and Variations on a Theme by Mozart. Here again is the version lengthening the first note of each unit. Example #150:

Then, here is a version where we triple the length of the lengthened notes. This version keeps the fast notes fast but gives our hands more time to relax between the bursts of fast notes. Example #151:

It is important to look at the next long note (in blue in the example above) before playing the following fast notes. In the example above, after playing the first interval, you would look sequentially at the G#, C#, and F# (the blue notes) as you play the scale. This process trains you to find visual landmarks in a passage and see groups of notes rather than individual notes.

We could lengthen the long notes even more if we needed to. In fact, some teachers maintain that the guitarist will gain the most benefit from this approach by exaggerating both the long and short values—making the long notes longer and the short notes faster.

Or, we could fall back on our "STOP—then Go" practice where we make the long notes unmetered fermatas to give our hands as much time as they want to relax. Not only does this approach help rid the playing mechanism of tension, but it also permits you to concentrate on smaller units of a tricky passage.

4. Lengthen a Particular Beat in Each Measure to Alter the Rhythm

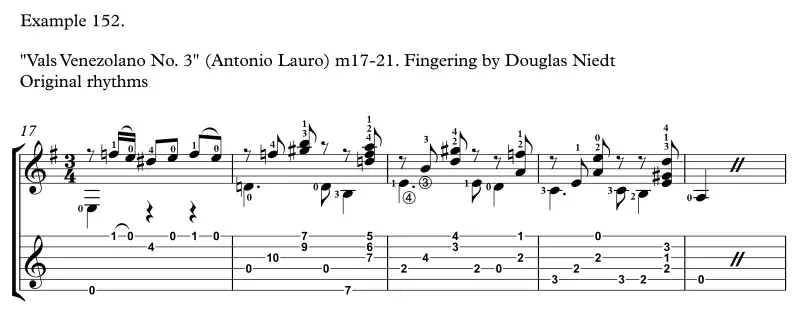

This approach works best in a fast piece on longer passages of 4-8 measures. For example, here is a phrase from Vals Venezolano No. 3 by Antonio Lauro. Example #152:

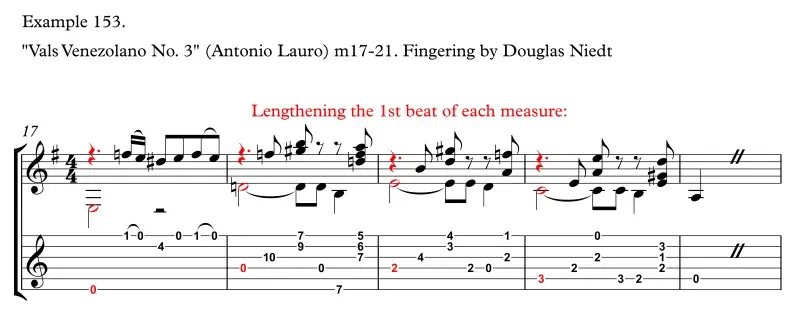

We can lengthen the first beat of each measure. Example #153:

Then, we can lengthen the second beat of each measure. Example #154:

Finally, we can lengthen the third beat of each measure. Example #155:

5. Insert a Very Long Pause (Fermata) and Play the Following Notes as Grace Notes to Alter the Rhythm

This type of rhythm practice is a form of speed bursts, which we will examine in another article. This strategy works best on rhythmically-even scales and sometimes on passages in an even rhythm with only a few intervals or chords.

In this scenario, we don't strictly notate the altered rhythms. Instead, we think of the lengthened notes as fermatas as in "STOP—then Go," followed by grace notes that we play very fast. On each long note (the fermatas), actively command a release of effort and switch off the muscles.

Not only does this approach help rid the playing mechanism of tension, but it also permits you to concentrate on smaller units of a tricky passage.

Let's look at how we generate this form of altered rhythm. Returning to the Introduction and Variations on a Theme by Mozart, first, we have the original. Example #156:

Next is the metrical strictly-notated altered rhythm of long-short-short. Example #157:

And finally, here is our new grace note version. Example #158:

Here are the conscious stages of this process:

- Play the note on the fermata and pause on it.

- Immediately release all effort. Think of a light switch going off.

- Command the muscles in both hands and arms to loosen and return to a state of balance.

- Release any stretched-out positions.

- Revel in the sensation of feeling physically at rest.

- Prepare mentally for the next burst of energy to play the following grace note or group of grace notes. Look at them and hear them in your head if possible. Take all the time you need to be one hundred percent certain that you will play the next group of grace notes correctly. In the early stages, you can take more time on some fermatas than others to do this. Later, it is best to make the fermatas equal in length, and each group of grace notes the same speed.

- Play the next grace note group only when you are mentally ready. Some teachers recommend playing the grace notes with a light touch, but others recommend an aggressive touch. I would try both and see which works best for you.

The fermatas need to be long enough for all this to occur. Then, as we get better and quicker, we can shorten the fermatas until they eventually disappear.

When you play the grace notes, they should be at your final target tempo. You are training your mind to think of groups of notes in one quick thought or gesture, which is more efficient than thinking of each and every note. Therefore, you are preparing your hands and mind to play the entire passage at the target tempo.

Sometimes, we may want to focus on one tricky part of a fast scale or passage. For example, in our scale from Capricho Árabe, many guitarists lose control of the final nine notes. Example #159:

We can apply our fermata-grace notes strategy to just the problematic final nine notes. For now, we will also eliminate the grace note glissando to focus on only the principal notes.

So, here is the unaltered, original rhythm (without the grace note) of the problematic final nine notes. Example #160:

We can choose to make any note of each group of four the long note. Let's begin by making the first note of each group of four the long note. If we lengthen the first note of each unit as we did in our previous strategy, we have this rhythmically-precise version. Example #161:

And now, here is our new fermata-grace note version with the 1st note of each group of four as the long fermata. Example #162:

We could also practice making the 2nd, 3rd, or 4th note of each group of four the long note (fermata) for additional mastery. For example, here is the 2nd note as the long note (fermata). Example #163:

Then, here is the 3rd note as the long note (fermata). Example #164:

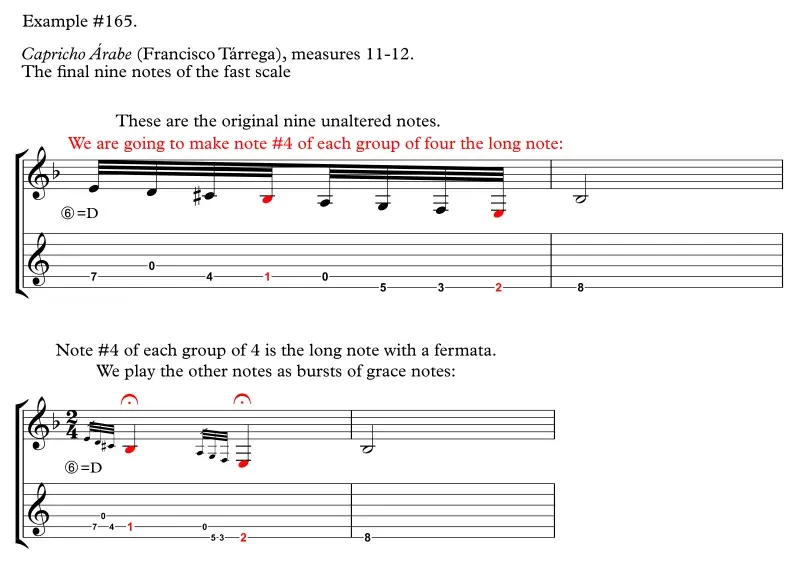

And finally, here is the 4th note as the long note (fermata). Example #165:

6. Change the Accents to Alter the Rhythm

This strategy works very well for scales and sometimes on other passages written in an even rhythm with few intervals or chords. We play the notes rhythmically evenly but make one note of a group loud and the others soft. Depending on the length and rhythmic organization of the scale, we can accent the notes in groups of 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, or 7.

Although you will vary the loudness of the notes, it is essential to keep their rhythmic values even. Some teachers recommend exaggerating the loudness of the accented notes and the softness of the other notes. Practicing with accents will develop your control so that ultimately, you will be able to either keep the volume of all the notes perfectly even or purposely accent particular notes.

Accenting the notes also helps diagnose and correct problems with alternating the right-hand fingers or not using the intended right-hand fingering. Accenting a note increases your awareness of which right-hand finger is plucking that note. You will often catch yourself using an unintended finger, especially at a string cross or after a slur.

Like the other altered rhythm tools, you can use this one once you can play the passage accurately at a slow speed to establish a foundation of control over each note's volume and ensure you are using your intended right-hand fingering.

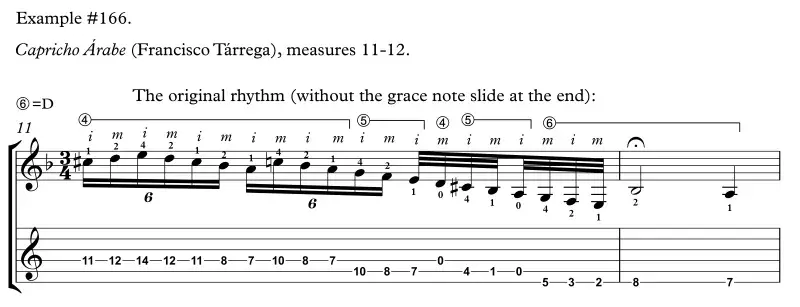

Let's look again at the scale in Capricho Árabe. Below is the original scale without the grace note slide at the end of measure 11. Example #166:

Now, I will alter the rhythm by accenting the notes in groups of 2. Example #167:

Then, I can accent the notes in groups of 3. Example #168:

Next, I can accent the notes in groups of 4. Example #169:

Finally, I can accent the notes in groups of 5. Example #170:

SUMMARY

In Part 1, we learned the benefits of practicing with altered rhythms and the following altered rhythm practice strategies:

- Alter the rhythm by applying the two basic dotted rhythms of long-short and short-long.

- Lengthen a particular note within a beat or unit.

- Use extended pauses on the lengthened notes.

- Lengthen a particular beat in each measure.

- Insert a fermata on the lengthened note and play the following note or notes as ultra-fast grace notes.

- Change the accents.

The strategies you use will depend on the passage you are trying to master. Some strategies will work on one passage but not another. Experiment with them all. When you find strategies that fit a passage, you will get great results.

Coming up in Part 9: MORE Altered Rhythm Patterns

DOWNLOADS

1. Download a PDF of the article with links to the videos. Depending on your browser, it will download the PDF (but not open it), open it in a separate tab in your browser (you can save it from there), or open it immediately in your PDF app.

Download the PDF: HOW TO LEARN A PIECE (SONG) ON THE CLASSICAL GUITAR Part 8 with embedded audio clips.