this is a blank placeholder

How to Learn a Piece

On the Classical Guitar

"Douglas who?"

Douglas Niedt is a successful concert and recording artist and highly respected master classical guitar teacher with 50 years of teaching experience. He is Associate Professor of Music (retired), at the Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City and a Fellow of the Henry W. Bloch School of Management—Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

Doug studied with such diverse masters as Andrés Segovia, Pepe Romero, Christopher Parkening, Narciso Yepes, Oscar Ghiglia, and Jorge Morel. Therefore, Doug provides solutions for you from a variety of perspectives and schools of thought.

He gives accurate, reliable advice that has been tested in performance on the concert stage that will work for you at home.

PURCHASE AN ALL-ACCESS PASS

TO THE VAULT OF CLASSICAL GUITAR TECHNIQUE TIPS

"Hello Mr Niedt,

My name's Gretchen, and I'm so happy I purchased an All-Access Pass to the Vault. I love your awesome technique tips. I'm amazed how much I have improved my playing.

Thank you!"

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR PROVEN STRATEGIES

THAT WILL MAKE YOU A BETTER GUITARIST?

Check out the game-changing tips in my Vault—I promise they will kick your playing up to the next level.

Purchase an All-Access Pass to the Vault.

It's a one-time purchase of only $36!

You receive full access to:

- Over 180 technique tips in The Vault.

- Special arrangements of Christmas music

- Arrangement of the beautiful Celtic song, Skellig

- Comprehensive guide, How to Master the Classical Guitar Tremolo

All that for a one-time payment of only $36.

Take me to the page to Purchase an All-Access Pass

Everything on the website carries a no-risk, money-back guarantee.

HOW TO LEARN A PIECE (SONG)

ON THE CLASSICAL GUITAR, Part 9

By Douglas Niedt

Copyright Douglas Niedt. All Rights Reserved.

This article may be reprinted, but please be considerate and give credit to Douglas Niedt.

*Estimated minimum time to read this article and listen to the audio clips: 45 minutes.

*Estimated minimum time to read the article, listen to the audio clips, and play through the musical examples: 2-4 hours.

NOTE: You can click the navigation links on the left (not visible on phones) to review specific topics or videos.

In Part 1, we laid the groundwork for learning a new song:

- We set up our practice space.

- We learned to choose reliable editions of the piece we are going to learn.

- We learned that it is essential to listen to dozens of recordings and watch dozens of videos to hear the big picture as we learn a new piece.

- We learned that it is important to study and analyze our score(s).

- We learned how to make a game plan for practicing our new piece.

- We learned why it is so vital NEVER to practice mistakes and the neuroscience behind it.

- We learned practice strategies to master small elements, including "The 10 Levels of Misery," which ensures we don't practice mistakes.

- We learned where to start practicing in a new piece.

- We learned that it is vital to master small elements first.

- We learned the two most fundamental practice tools—The Feedback Loop and S-L-O-W Practice.

In Part 4, we learned how to use the "Slam on the Brakes" and "STOP—Then Go" practice strategies to:

In Part 5, we learned how to practice with the right hand alone to:

- Apply planting or double-check the precision of your planting technique

- Correct or improve the balance between the melody, bass, and accompaniment

- Apply or improve string damping

- Master passages with difficult string crossings

In Part 6, we learned how to practice with the left hand alone to learn, improve, and master:

- The "lag behind" technique

- How to lift fingers to avoid string squeaks

- Left-hand finger preparation

- Synchronization of left-hand finger movements

In Part 7, we learned more on how to practice with the left hand alone to learn, improve, and master:

- Shifts

- Pre-planting the left-hand fingers

- Collapsing (hyperextending) the tip of the first finger going into and out of a bar chord

- Difficult chord changes without tiring, injuring, or "locking up" the left hand by practicing with light finger pressure

In Part 8 (in Part 1), we began learning how to practice with Altered Rhythms. We learned the benefits and six specific strategies:

- How to practice the most common altered rhythms: dotted rhythms

- How to lengthen a particular note within each beat to alter the rhythm

- How to use extended pauses in altered rhythms to reduce tension in the hands

- How to lengthen a particular beat in each measure to alter the rhythm

- How to insert a very long pause (fermata) and play the following notes as grace notes to alter the rhythm

- How to change the accents to alter the rhythm

PRACTICING IN ALTERED RHYTHMS, Part 2

MORE Altered Rhythm Patterns

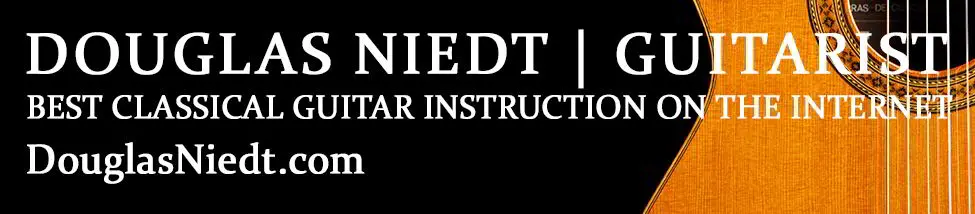

Here are two handy-dandy charts compiled by piano pedagogue Graham Fitch of altered rhythm patterns you can apply to your pieces. The first chart is an "Altered Rhythms Chart for Divisions of 2." Use these rhythms on a passage where the notes are in groups of 2, 4, 8, or 16. Example #171:

This second chart is an "Altered Rhythms Chart for Divisions of 3." Use these rhythms on a passage where the notes are in groups of 3, 6, or 12. Example #172:

I find it easier to practice a passage with these patterns if I write down the passage with each altered rhythm. Please note:

- You don't need an expensive notation program to do this. Instead, write the passage out with pencil and paper, the old-fashioned quick and easy way!

- Plus, if you write the passages out on paper, you don't need to figure out and write in the meter (3/4, 9/4, 13/8, etc.) as I did in this technique tip. Instead, write the rhythmic values only (quarter notes, 8th notes, dotted 8th notes, 16th notes, etc.).

- Include any slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs)

- Finally, be sure to write in the left AND RIGHT-HAND fingerings so that you practice them correctly.

TRY IT OUT!

- Play or listen to some of the examples below to understand the process.

- Then, apply some of these patterns to a passage from a piece you already know or are learning.

- Play the original rhythm first. Then practice an altered rhythm for a few minutes. Then return to the original rhythm. You can alternate back and forth randomly. Experiment with how much to practice the altered rhythm and how much to play the original rhythm.

- Use other tools in conjunction with altered rhythms. For instance, practicing with the right hand alone can be very helpful. I highly recommend using a metronome occasionally. It will help you to judge the precision of your rhythms.

- If you have trouble playing an altered rhythm precisely, break down the passage into smaller units. Then, put it back together.

ALTERED RHYTHMS—DIVISIONS OF 2

How to Apply Altered Rhythms in Divisions of 2 to a Scale

It is easiest to apply these altered rhythms to scales, so my examples will start there. But remember, except for the simplest altered rhythms, you will find it easier to practice if you write down the scale in the rhythm of each altered pattern.

- You don't need an expensive notation program to do this. Instead, write the passage out with pencil and paper, the old-fashioned quick and easy way!

- Plus, if you write the passages out on paper, you don't need to figure out and write in the meter (3/4, 9/4, 13/8, etc.) as I did in this technique tip. Instead, write the rhythmic values only (quarter notes, 8th notes, dotted 8th notes, 16th notes, etc.).

- Include any slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs)

- Finally, be sure to write in the left AND RIGHT-HAND fingerings so that you practice them correctly.

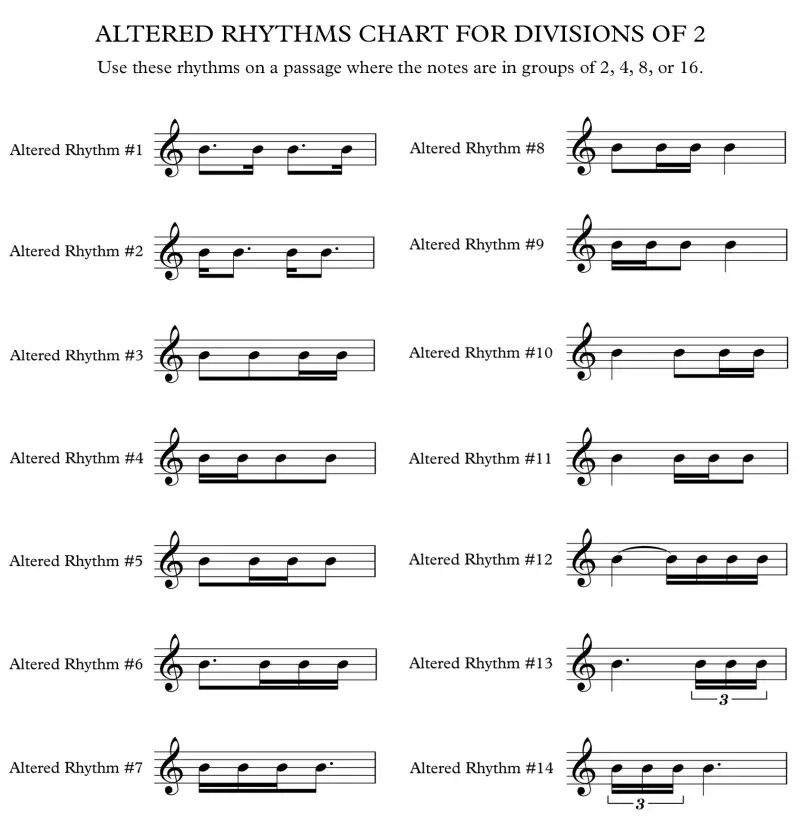

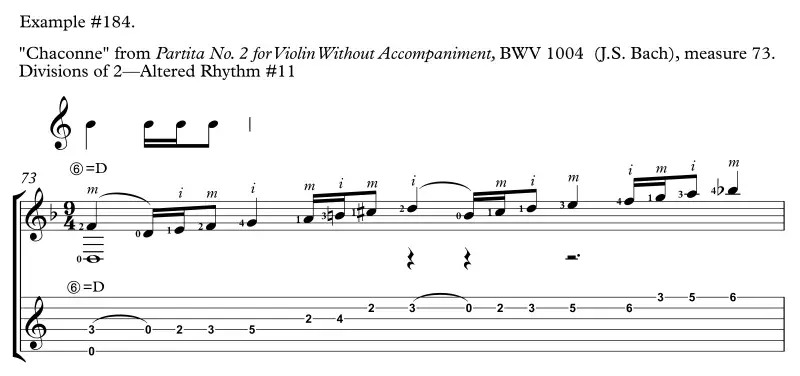

A Scale from the Bach Chaconne

Here is a scale from measure 72 of the "Chaconne" from Partita No. 2 for Violin without Accompaniment, BWV 1004 by J.S. Bach. This is the original rhythm. Example #173:

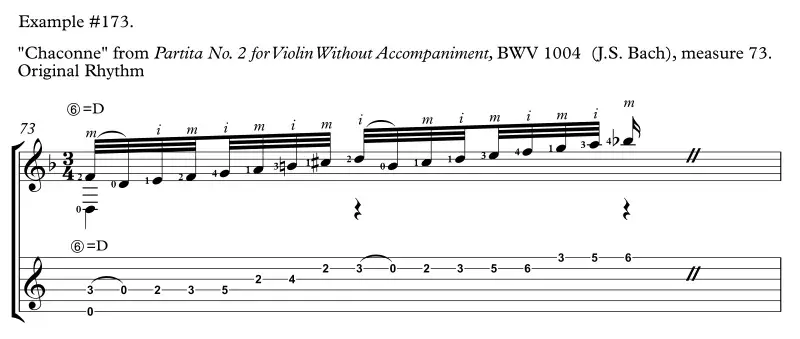

Following is the same scale notated in each of the altered rhythms from the "Altered Rhythms Chart for Divisions of 2." After each example, you can play the audio file to hear what it sounds like.

Let's get started! Here is altered rhythm #1 followed by rhythms #2 through #14.

The first altered rhythm is the first of the two basic dotted rhythms (long-short) we learned in Part 1. Example #174:

The next example is the second of the two basic dotted rhythms (short-long) we learned in part 1. Example #175:

How to Apply Altered Rhythms in Divisions of 2 to a Passage from a Piece (not a scale)

It is more complicated to apply altered rhythms to non-scale passages. Therefore, I highly recommend writing out the passage in the altered rhythms you wish to practice as I have done here. Remember:

- You don't need an expensive notation program to do this. Instead, write the passage out with pencil and paper, the old-fashioned quick and easy way!

- Plus, if you write the passages out on paper, you don't need to figure out and write in the meter (3/4, 9/4, 13/8, etc.) as I did in this technique tip. Instead, write the rhythmic values only (quarter notes, 8th notes, dotted 8th notes, 16th notes, etc.).

- Include any slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs)

- Finally, be sure to write in the left AND RIGHT-HAND fingerings so that you practice them correctly.

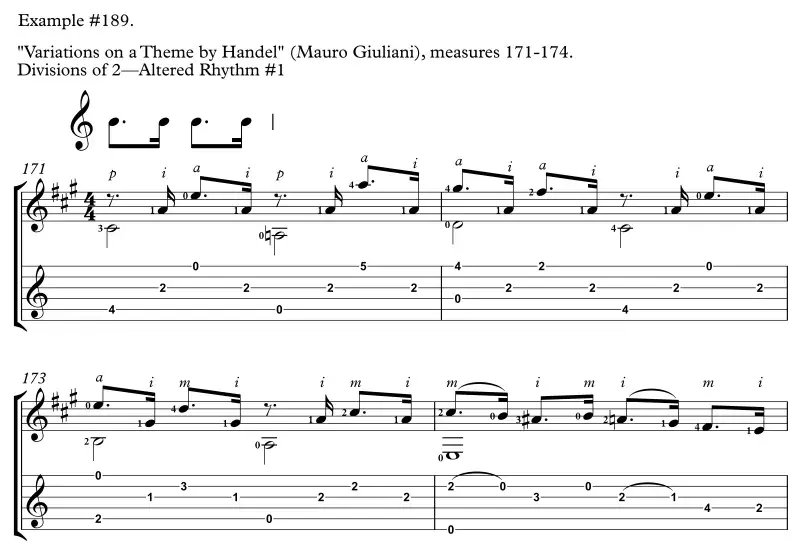

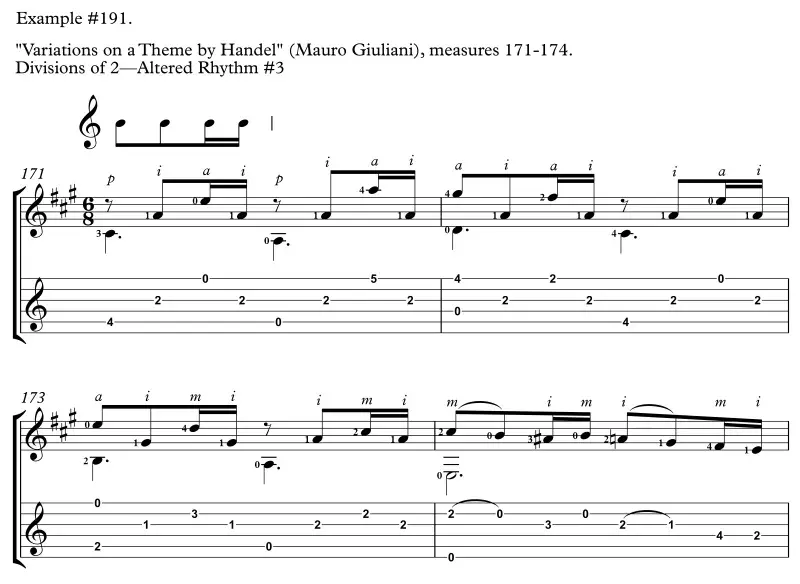

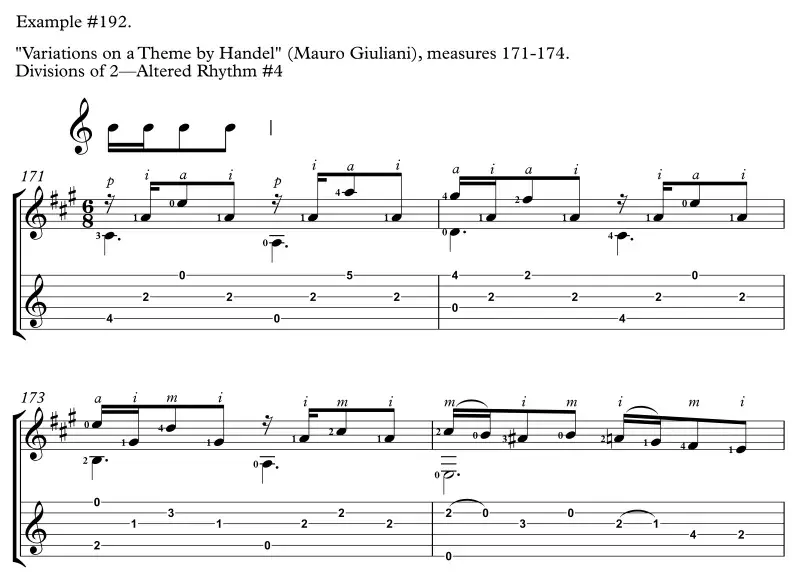

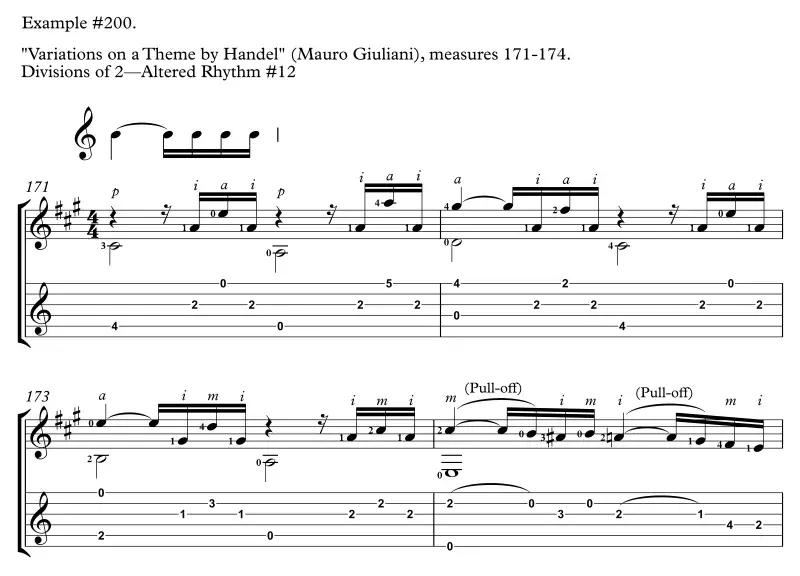

A Passage from Variations on a Theme by Handel by Mauro Giuliani

Here are measures 171-174 from Mauro Giuliani's Variations on a Theme by Handel. These are the original rhythms. Example #188:

Following is the same passage notated in each of the altered rhythms from the "Altered Rhythms Chart for Divisions of 2." After each example, you can play the audio file to hear what it sounds like.

Let's get started! Here is altered rhythm #1 followed by altered rhythms #2 through 14. Example #189:

The first altered rhythm is the first of the two basic dotted rhythms (long-short) we learned in Part 1. Example #189:

The next example is the second of the two basic dotted rhythms (short-long) we learned in part 1. Example #190:

ALTERED RHYTHMS—DIVISIONS OF 3

How to Apply Altered Rhythms in Divisions of 3 to a Scale

It is easiest to apply altered rhythms to scales, so my examples will start there. But remember, except for the simplest altered rhythms, you will find it easier to practice if you write down the scale in the rhythm of each altered pattern. Please note:

- You don't need an expensive notation program to do this. Instead, write the passage out with pencil and paper, the old-fashioned quick and easy way!

- Plus, if you write the passages out on paper, you don't need to figure out and write in the meter (3/4, 9/4, 13/8, etc.) as I did in this technique tip. Instead, write the rhythmic values only (quarter notes, 8th notes, dotted 8th notes, 16th notes, etc.).

- Include any slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs)

- Finally, be sure to write in the left AND RIGHT-HAND fingerings so that you practice them correctly.

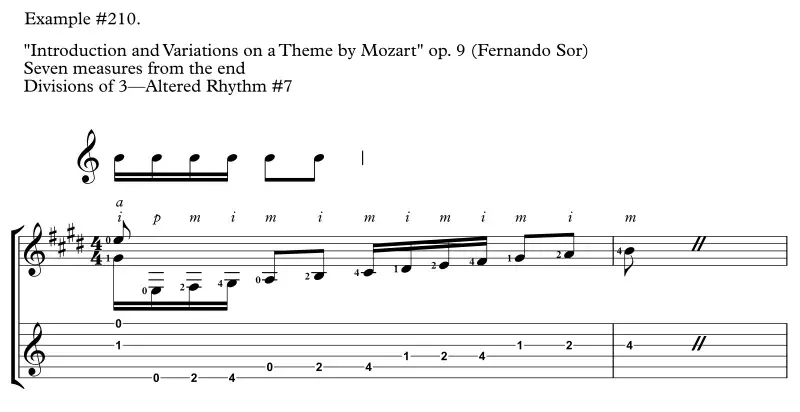

A Scale from Introduction and Variations on a Theme by Mozart by Fernando Sor

Here is a scale from the last seven measures of Fernando Sor's Introduction and Variations on a Theme by Mozart. Here is the scale in its original rhythm. Example #203:

Following is the same scale notated in each of the altered rhythms from the "Altered Rhythms Chart for Divisions of 3." After each example, you can play the audio file to hear what it sounds like.

Let's get started! Here is altered rhythm #1 followed by altered rhythms #2 through 8. Example #204:

How to Apply Altered Rhythms in Divisions of 3 to a Passage from a Piece (not a scale)

It is more complicated to apply altered rhythms to non-scale passages. Therefore, I highly recommend writing out the passage in the altered rhythms you wish to practice as I have done here. Remember:

- You don't need an expensive notation program to do this. Instead, write the passage out with pencil and paper, the old-fashioned quick and easy way!

- Plus, if you write the passages out on paper, you don't need to figure out and write in the meter (3/4, 9/4, 13/8, etc.) as I did in this technique tip. Instead, write the rhythmic values only (quarter notes, 8th notes, dotted 8th notes, 16th notes, etc.).

- Include any slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs)

- Finally, be sure to write in the left AND RIGHT-HAND fingerings so that you practice them correctly.

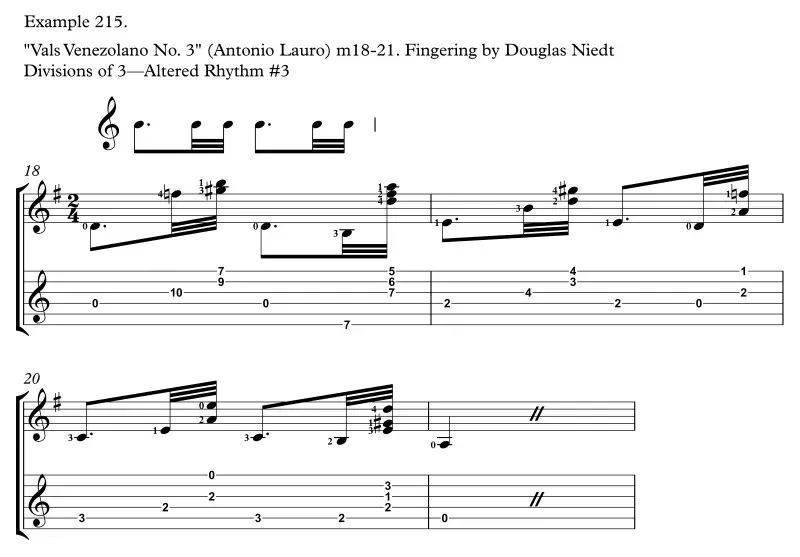

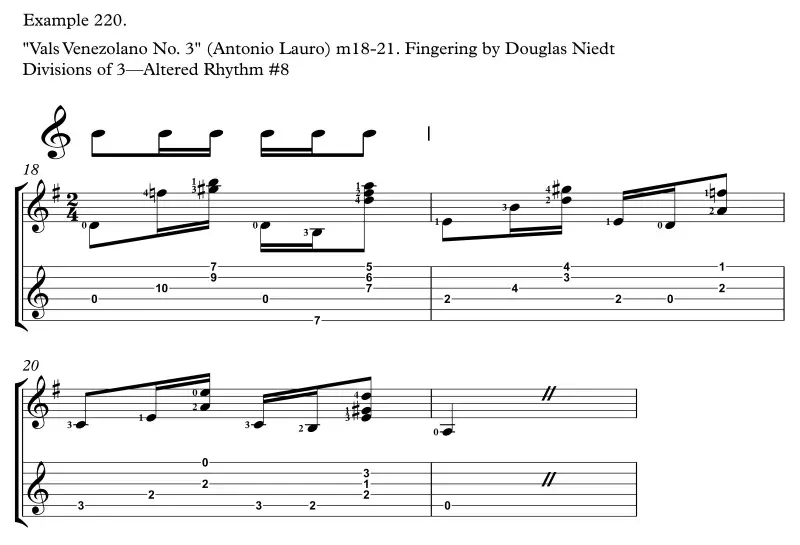

A Passage from Vals Venezolano No. 3 by Antonio Lauro

Here are measures 18-21 from Antonio Lauro's Vals Venezolano No. 3. Here are the original rhythms. Example #212:

Following is the same passage notated in each of the altered rhythms from the "Altered Rhythms Chart for Divisions of 3." After each example, you can play the audio file to hear what it sounds like.

Let's get started! Here is altered rhythm #1 followed by altered rhythms #2 through #8. Example #213:

The Downside of Practicing Altered Rhythms

The primary downside of practicing altered rhythms is doing it too much. You could practice so many rhythmic patterns that using this tool indiscriminately can waste a lot of valuable practice time. Yes, you will fill in your allotted practice time, but there is a point of diminishing returns. Again, there are so many ways to practice altered rhythms that one could easily spend several hours on a passage of four measures doing nothing else. That is overkill and unnecessary. I find it is fun to practice with altered rhythms, but remember that they won't fix everything, and you don't want to overuse this tool and neglect other valuable practice tools.

Some teachers say that spending too much time practicing altered rhythms can lend an overly formulaic, mechanical structure to the practice session. On the other hand, I find that playing a passage several times, once as written, then with some altered rhythms, again as written, then with another altered rhythm, etc., keeps me more engaged than if I practiced the passage ten times in the original version.

I recommend starting with the two basic dotted rhythms. Then, if you are not getting results, explore more patterns and practice those you find most challenging. You don't need to practice every possible rhythm. And never practice a passage with altered rhythms without listening critically. Be sure that the notes remain clean when you alter the rhythm and the altered rhythm is exact. Hear it as a musical entity, so it doesn't feel like a mechanical exercise.

SUMMARY

Altered rhythm practice is great, but don't overdo it. Use it judiciously and combine it with other practice tools. You will find the benefits are fantastic. Practicing in altered rhythms really works. You will be amazed by the results in just one to two days.

Once again, from Part 1:

The Benefits of Practicing Altered Rhythms

Build Good Muscle Memory and Dismantle Bad Muscle Memory to Construct New Neural Pathways

When we change the rhythm of a passage, we come to know it from a variety of different angles. As a result, the brain sees the patterns differently with each rhythmical variation. Therefore, it is easier to play faster, evenly, and more accurately when we return to the original.

Practicing altered rhythms seems to break up muscle memory; especially old, entrenched muscle memory that produces the same mistakes day after day, month after month, and year after year. On a piece you have been playing a long time, the pauses will break the momentum of old, faulty muscle memory that you can now replace with the correct movements. Remember our discussion on the importance of myelinating the correct neural pathways?

Improve Finger Preparation

The long notes in an altered rhythm help train the fingers on both hands to prepare for the following fast note or notes. A pause allows the fingers on both hands to hover above the next note or string, reinforcing the muscle memory needed to play that note.

Learn to Make Fast Finger Movements

Practicing with altered rhythms sharpens the reflexes. When you practice with altered rhythms, you prolong some notes but speed up other notes or groups of notes into a reflex, tricking your brain and body into playing fast without feeling like you are increasing the overall tempo. In other words, you may not have the skill to play all the notes in a scale fast, but an altered rhythm makes it possible for you to play some of the notes and the transitions from note to note very fast, almost as a reflex. If you change the rhythm again, you will learn to play other groups of notes and the transitions very fast. After practicing several rhythms, you will soon have the ability to play ALL the notes and transitions fast, and voila, you have a complete scale at a speed you thought you could never attain.

By treating groups of notes as reflexes, practicing in altered rhythms in some instances can improve the synchronization of the two hands.

Reduce Tension in the Hands

When we play fast notes, we use an explosion of energy. Over a few measures, tension can build in the hands and produce mistakes or slow the hands down. We can use the long notes in our altered rhythms as an opportunity to train the hands and fingers to release that energy, so they learn to stay relaxed through an entire passage.

Improve Slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs)

We even apply the altered rhythms to any slurs in the passage. Practicing the altered rhythms with the slurs will help improve the clarity, rhythmic precision, and strength of your hammer-ons and pull-offs.

Correct Problems with Right-Hand Fingering

Accenting the notes in different patterns helps diagnose and correct problems with alternating the right-hand fingers or not using the intended right-hand fingering. Accenting a note increases your awareness of which right-hand finger is plucking that note. You will often catch yourself using an unintended finger, especially at a string cross or after a slur.

Maintain Focus and Engagement

Practicing with altered rhythms also keeps the brain engaged. For example, if you repeat a passage ten times, it is hard to maintain your focus 100% of the time. But if you play the passage once or twice in the original rhythm, change to an altered rhythm, go back to the original, change to a second altered rhythm, go back to the original, etc., your brain and hands must constantly readjust and think about what is happening. The procedure also forces you to listen more closely to each repetition.

DOWNLOADS

1. Download a PDF of the article with links to the videos. Depending on your browser, it will download the PDF (but not open it), open it in a separate tab in your browser (you can save it from there), or open it immediately in your PDF app.

Download the PDF: HOW TO LEARN A PIECE (SONG) ON THE CLASSICAL GUITAR Part 9 with embedded audio clips.