this is a blank placeholder

How to Learn a Piece

On the Classical Guitar

"Douglas who?"

Douglas Niedt is a successful concert and recording artist and highly respected master classical guitar teacher with 50 years of teaching experience. He is Associate Professor of Music (retired), at the Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City and a Fellow of the Henry W. Bloch School of Management—Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

Doug studied with such diverse masters as Andrés Segovia, Pepe Romero, Christopher Parkening, Narciso Yepes, Oscar Ghiglia, and Jorge Morel. Therefore, Doug provides solutions for you from a variety of perspectives and schools of thought.

He gives accurate, reliable advice that has been tested in performance on the concert stage that will work for you at home.

PURCHASE AN ALL-ACCESS PASS

TO THE VAULT OF CLASSICAL GUITAR TECHNIQUE TIPS

"Hello Mr Niedt,

My name's Gretchen, and I'm so happy I purchased an All-Access Pass to the Vault. I love your awesome technique tips. I'm amazed how much I have improved my playing.

Thank you!"

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR PROVEN STRATEGIES

THAT WILL MAKE YOU A BETTER GUITARIST?

Check out the game-changing tips in my Vault—I promise they will kick your playing up to the next level.

Purchase an All-Access Pass to the Vault.

It's a one-time purchase of only $36!

You receive full access to:

- Over 180 technique tips in The Vault.

- Special arrangements of Christmas music

- Arrangement of the beautiful Celtic song, Skellig

- Comprehensive guide, How to Master the Classical Guitar Tremolo

All that for a one-time payment of only $36.

I want to purchase an All-Access Pass

HOW TO LEARN A PIECE (SONG)

ON THE CLASSICAL GUITAR, Part 10

By Douglas Niedt

Copyright Douglas Niedt. All Rights Reserved.

This article may be reprinted, but please be considerate and give credit to Douglas Niedt.

*Estimated minimum time to read this article and listen to the audio clips: 45 minutes.

*Estimated minimum time to read the article, listen to the audio clips, and play through the musical examples: 2-4 hours.

NOTE: You can click the navigation links on the left (not visible on phones) to review specific topics or videos.

In Part 1, we laid the groundwork for learning a new song:

- We set up our practice space.

- We learned to choose reliable editions of the piece we are going to learn.

- We learned that it is essential to listen to dozens of recordings and watch dozens of videos to hear the big picture as we learn a new piece.

- We learned that it is important to study and analyze our score(s).

- We learned how to make a game plan for practicing our new piece.

- We learned why it is so vital NEVER to practice mistakes and the neuroscience behind it.

- We learned practice strategies to master small elements, including "The 10 Levels of Misery," which ensures we don't practice mistakes.

- We learned where to start practicing in a new piece.

- We learned that it is vital to master small elements first.

- We learned the two most fundamental practice tools—The Feedback Loop and S-L-O-W Practice.

In Part 4, we learned how to use the "Slam on the Brakes" and "STOP—Then Go" practice strategies to:

In Part 5, we learned how to practice with the right hand alone to:

- Apply planting or double-check the precision of your planting technique

- Correct or improve the balance between the melody, bass, and accompaniment

- Apply or improve string damping

- Master passages with difficult string crossings

In Part 6, we learned how to practice with the left hand alone to learn, improve, and master:

- The "lag behind" technique

- How to lift fingers to avoid string squeaks

- Left-hand finger preparation

- Synchronization of left-hand finger movements

In Part 7, we learned more on how to practice with the left hand alone to learn, improve, and master:

- Shifts

- Pre-planting the left-hand fingers

- Collapsing (hyperextending) the tip of the first finger going into and out of a bar chord

- Difficult chord changes without tiring, injuring, or "locking up" the left hand by practicing with light finger pressure

In Part 8, we began learning how to practice with Altered Rhythms. We learned the benefits and six specific strategies:

- How to practice the most common altered rhythms: dotted rhythms

- How to lengthen a particular note within each beat to alter the rhythm

- How to use extended pauses in altered rhythms to reduce tension in the hands

- How to lengthen a particular beat in each measure to alter the rhythm

- How to insert a very long pause (fermata) and play the following notes as grace notes to alter the rhythm

- How to change the accents to alter the rhythm

In Part 9, we concluded our discussion of practicing with Altered Rhythms. We learned:

A very powerful tool in our toolbox to help us master a piece is to practice the individual voices of a song, section, or measure. However, it is a complicated tool, and to use it, you must learn to identify the individual voices in your music. In order to do that, it will be helpful to understand the history and background of how the notation of voices works. So, think of Part 10 as an introduction, perhaps as RTFM—Read The Freaking Manual (to put it in polite terms). Then, I will explain how to use the tool in detail in Part 11.

HOW TO IDENTIFY THE INDIVIDUAL VOICES OF YOUR MUSIC

Most pieces consist of voices or parts. A guitar piece or arrangement containing two or more voices sounds good because it seems as though two or more guitars are playing simultaneously. Identifying, hearing, and playing the individual voices is essential for learning or understanding any song. It doesn't matter whether it is a beginning study by Sor or Giuliani, a three-part fugue by Bach, or anything in between. This knowledge provides several benefits:

- The most obvious benefit is that knowing which notes form the melody will help you practice playing those notes more prominently than those in subordinate voices. Usually, making the melody prominent is key to making a piece sound its best.

- We can learn which notes form the accompaniment and practice it independently. That way, we can easily hear any flaws in the accompaniment and fix them.

- If you know which voice is which, you can adjust the relative balance between two or more parts with great precision.

- Separating the music into its voices allows us to see the independent rhythms of each part so that we hold the notes for their correct duration.

- Understanding how each note within a voice connects to the following note helps eliminate choppy playing.

- We can choose whether to play the melody or the bass part as a pure line (only one note ringing at a given moment) or allow notes to ring together.

- We can detect bad left-hand fingering.

- We can improve the tone quality of a voice.

- We can improve the clarity of the voices (eliminate buzzes and muted notes).

- In contrapuntal music, we can learn to hear the individual voices and how they interact. Then, we can apply practice tools to make those interactions crystal clear.

- If we can identify the voices in our music, we can use some advanced practice strategies in which we practice the voices separately to improve several elements of our playing.

- An awareness of the voices of the music enables you to hear and appreciate the intricacies, uniqueness, creativity, and wonder of the composer or arranger's work. That awareness will permeate your playing, and your listeners will also sense and hear it.

Sometimes a song, section, or a few measures of a song will contain one part or voice. Example #221:

If I add a bass part to the example above, the Classic Dance now has two voices or parts. I color-coded the notes to make it easy to see the two voices. Example #222:

Notice that the note stems of the upper voice point upward, and the note stems of the lower voice point downward. Soon, you will understand why that is important.

Notice that the note stems of the upper voice point upward, and the note stems of the lower voice point downward. Soon, you will understand why that is important.

Other songs may have three or more parts or voices. Here is an example from an Andantino by Mauro Giuliani that contains three voices. The notation here is more complicated, but I color-coded it to make it easier to see the three voices. Notice that the note stems of the upper voice point upward, but the note stems of the two lower voices point downward. Example #223:

In each of these examples, it is evident:

- How many voices are in the music

- Which notes belong to which voices

- What the rhythmic durations are of the notes within each voice

But in many pieces, it may be challenging to figure out how many voices are present, which notes belong to which voice, or to answer even the fundamental question, "Where is the melody?" For example, in classical and fingerstyle guitar notation, the composer or arranger often uses a shorthand or abbreviated method of notation for ease of reading, but it can obfuscate the individual voices.

For example, what is the melody in this beginning piece by Fernando Sor? Example #224:

Hint: it isn't the bottom part whose note stems point downward NOR all of the notes in the top part whose note stems point upward.

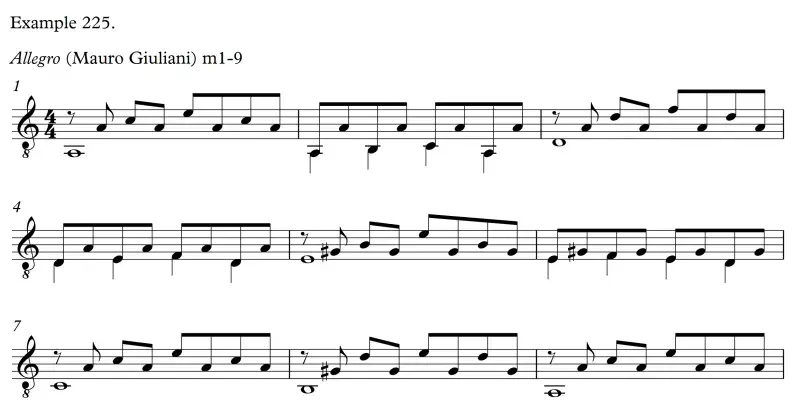

Or where is the melody in this beginning piece by Mauro Giuliani? Example #225:

Hint: the melody is some of the notes in the top part and some in the bottom part. But which ones?

We will do some sleuthing and find the melody in both of these pieces a little later. If you want to learn to unravel the voicing in songs such as these and in more complex pieces, it helps immensely to know a little history and background of how the notation of voices works.

A DEEP DIVE INTO VOICES AND THEIR TERMINOLOGY

I am going to explain:

- How pieces divide into voices and parts

- How to determine which notes belong to which voice

- How to decipher the internal rhythms within each independently moving voice

Four-Part Harmony and Choral Music

The concept of voices stems from four-part harmony, an essential element of the musical language of masters such as Bach, Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, and many others. The concept developed over centuries, and composers and arrangers still use it today.

Four-part harmony is a traditional system of organizing harmonies into four parts or "voices." The voices are the four familiar voices that make up a choir: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass (we call it SATB). Soprano and alto are women's voices, and tenor and bass are men's voices. In descending order, the soprano is the highest-pitched voice, followed by the alto, the tenor, and the bass, which is the lowest-pitched voice.

Composers often write vocal music for an SATB choir on four staffs (also called "staves"), one for each voice. This method of notation is called an "open score."

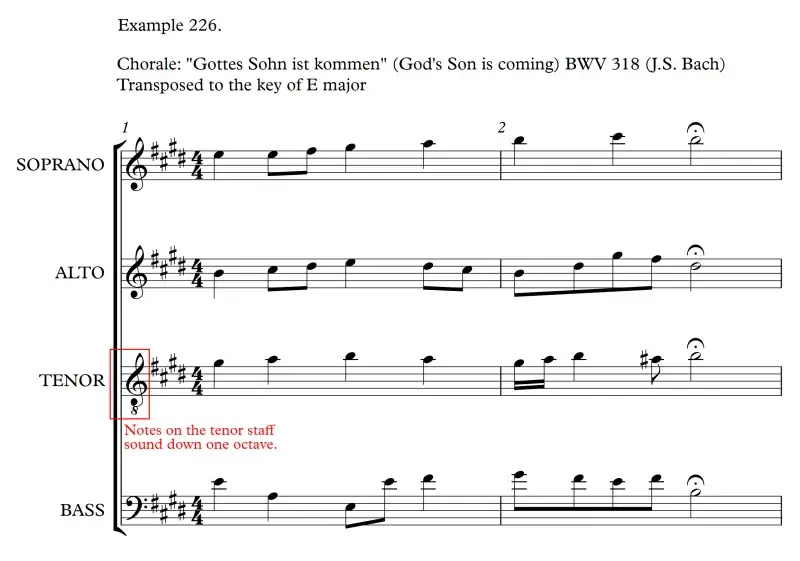

Here is an excerpt from J.S. Bach's chorale, Gottes Sohn ist kommen (God's Son is coming) BWV 318. I transposed it to the key of E major so that later, it will be easier to examine on the guitar fretboard. Example #226:

The soprano is always on top in an open score, followed by the alto, tenor, and bass.

Note that the soprano and alto voices use the treble clef:

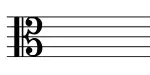

However, the tenor voice uses a clef called the treble clef octave-down, which means the notes sound an octave lower than written:

The bass voice uses the bass clef:

In an open score, it is obvious which note belongs to which voice because each voice or part is on a separate staff.

But composers also write in a format called "short score." Some call it a "choir reduction." A short score is only two staves with two voices on each stave. The soprano and alto voices share the treble clef staff, and the tenor and bass voices share the bass clef staff. Here is the same Bach chorale notated in the short score format. Example #227:

THE DIRECTION OF NOTE STEMS IS IMPORTANT! THEY HELP TO DIFFERENTIATE THE VOICES ON THE PRINTED PAGE.

Notice that on the treble clef staff, the notes belonging to the soprano voice have their note stems pointing up. On the other hand, the notes belonging to the alto voice have their note stems pointing down.

Likewise, on the bass clef staff, the notes belonging to the tenor voice have their note stems pointing up. Conversely, the notes belonging to the bass voice have their note stems pointing down.

Here is the example again, with the notes colorized to make it easier to distinguish the voices. Example #228:

The term "voice" or "part" refers to any musical line, whether a melody sung by singers or a part played on an instrument.

For example, music for a string orchestra resembles that of the open choral score. We often treat the string instruments as a four-part choir. The violins are on top, the violas in the middle, and the cellos and double basses on the bottom. The violins use the treble clef, the cellos and double basses use the bass clef, but the violas use the alto clef:

Here is an example of the four-part orchestral strings "choir" from Symphony No. 1 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Example #229:

Note that in older scores such as this, the double basses often doubled (played the same notes as) the cellos. Therefore, there are only four staves.

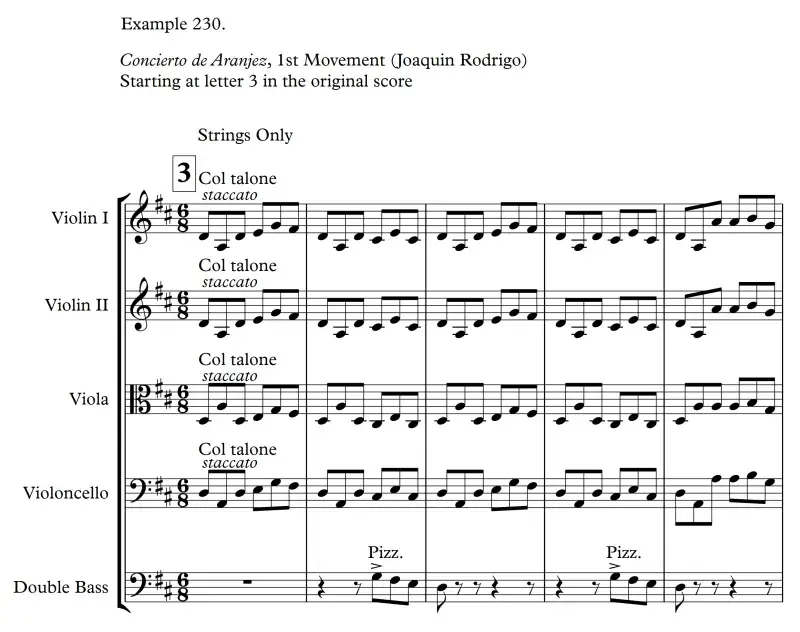

However, in post-classical music, the double basses more commonly played an independent bass part. Therefore, the modern common practice is to use five staves to show all the voices. Here is an example from the famous Concierto de Aranjuez for guitar and orchestra by Joaquin Rodrigo. Example #230:

Sometimes the composer will divide a string part into two groups of players. One group will play one note, and the other group another note. We call this "divisi" (Italian for divided). Notice that even in an orchestra score, the note stems of each divisi part go in different directions to differentiate these additional voices. Here is another example from Rodrigo's Concierto de Aranjuez. Example #231:

But again, we use the term "voices" in all instrumental music, not just string orchestras. For example, in a song performed by a rock band, the voices might be the singer, lead guitar, rhythm guitar, and bass guitar. In a solo guitar piece, the voices might be the melody line, accompaniment line, and bass line.

Music moves in two dimensions

You may wonder, "Why the in-depth explanation of four-part harmony and how voices work? What's the big deal? I play three, four, five, and six-part music (chords) on the guitar all the time."

Understanding the notation of voices will help you figure out where the voices are in your songs. Because we write guitar notation on one staff, it can be challenging to figure out which notes belong to which voice.

Understand that multi-part music moves in two dimensions. First, because each part combines simultaneously, we hear the notes as intervals and chords. This is the vertical or harmonic dimension. You can see it here in our Bach chorale. Example #232:

But the parts also move as independent melodies. This is the melodic or horizontal dimension. Again, you can see this in our Bach chorale. Example #233:

Next is the Bach chorale notated on two guitar staves to make all of this easier to see. Example #234:

The Limitations of Guitar Notation

In music with three or four independent parts, it is relatively easy to see which notes belong to which voices when we notate it as an open score, short score, or in the case of the guitar, on two staves.

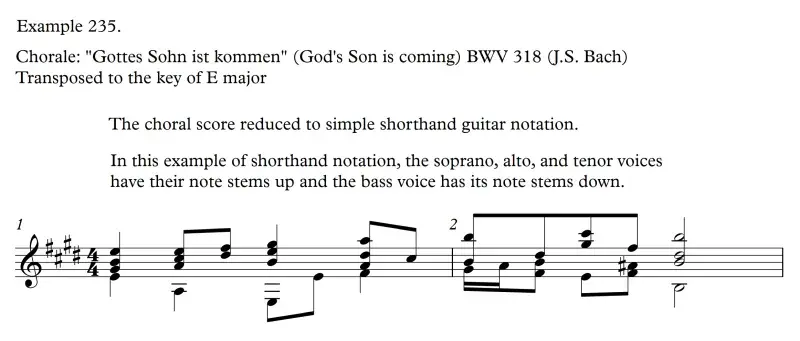

Our problems begin when we notate multi-voice music on one guitar staff. Guitarists and composers often use an abbreviated form of notation I call "shorthand guitar notation." In shorthand guitar notation, we stem the notes belonging to two or more independent voices together. For example, the soprano, alto, and tenor may share the same note stem. If I take our Bach chorale and notate it on one guitar staff in shorthand guitar notation, it looks like this. Example #235:

Notating music in shorthand guitar notation captures the vertical dimension very well. We can easily see the chords formed by the vertical alignment of the notes.

But in the horizontal dimension, it is no longer clear which notes belong to which voice. Example #236:

Also, the shorthand guitar notation cannot capture the true rhythmic durations of the notes in each individual voice. Example #237:

To clarify which notes belong to which voice and the precise duration of every note within each voice, we can use what I call "Advanced Guitar Notation." In this type of notation, we don't combine two or three voices onto one note stem as I did above in the shorthand notation. Instead, each note has its own note stem. Also, all the notes comprising a given voice have their stems either going up or down. Finally, we occasionally shift the visual position of a notehead slightly to the left or right on the page to clarify its independence from the notes around it. Example #238:

Now, we can easily pick out which note belongs to which voice, and the rhythmic duration of each note is clear. However, the notation is complex and harder to read than the shorthand guitar notation. For that reason, many composers and arrangers use simple shorthand guitar notation in pieces where the voices and rhythmic durations are apparent. But if the horizontal movement of the voices in a song is unclear or complicated, the advanced style of notation is best at showing the voice leading.

But you may say, "Well, that's all fine and dandy, but I'm not going to play any Bach chorales anytime soon." But you have to realize that most songs and arrangements that sound good on the classical guitar are those with two or more voices whose individual parts move horizontally and independently in different rhythms. The multi-voice, independently moving parts make a piece or arrangement sound "full." Without that, the music sounds empty, or the arrangement sounds like it's for a beginner.

So, for example, there are three distinct parts in my arrangement of Girl from Ipanema. As the melody sings in the upper voice and an independent bass part provides support in the lower voice, a fluid and ever-changing samba rhythm swings gently but continuously in the middle voice. The three parts are distinct and uninterrupted. Example #239:

Watch me play this passage from Girl from Ipanema. Listen to the three independent voices or parts. Watch Video #40.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right:

Video #40: Girl from Ipanema (Antônio Carlos Jobim) measures 20-32

Once you are clear about the voice leading in a piece or arrangement, you can focus on practicing the individual voices, which will tremendously improve your performance of a song. I will explain how to do that in Part 2.

Notation of Voices in Guitar Music

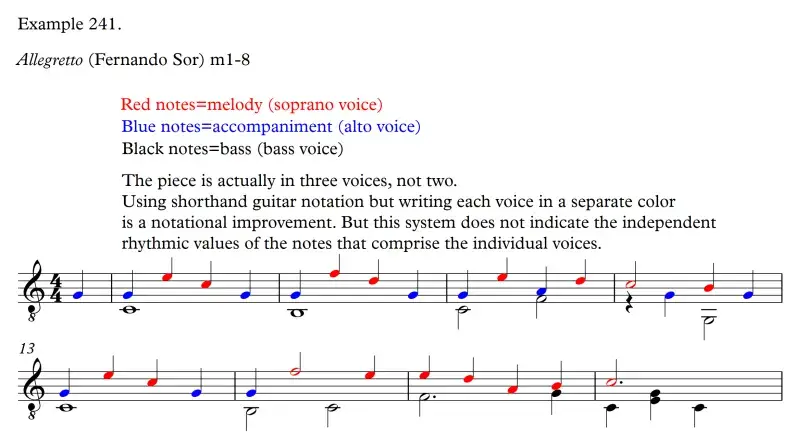

Even in simple songs, shorthand guitar notation can be misleading. For instance, near the beginning of this article, I showed you this Allegretto by Fernando Sor and asked, "What is the melody?" Sor's shorthand guitar notation makes it appear like the piece is in two parts: a melody and bass line. Example #240:

That doesn't sound good. The problem is that the piece is not in two parts; it is in THREE parts.

So here it is again in shorthand guitar notation, but this time with each voice in a different color. Example #241:

Again, from a casual glance at the original notation, you might not realize that the song is in three voices. But once you hear it, you discover more is going on than only two voices.

But what about the rhythmic values of those voices? You might say, "Well, once I start playing it, I will know which notes to hold." If you are an advanced player, maybe that is correct. But I doubt whether that will be true for beginners. So to understand the internal rhythms of the three independently moving voices, it helps to write out the music using advanced notation. Example #242:

Now, we can see which notes we should hold and allow to ring. We can see how the three voices move independently in the horizontal dimension. Also, take a closer look at measures 15 and 16. Even in relatively easy pieces, there can be different ways to interpret the voice leading. Notice the two interpretations I provide for measures 15 and 16. Both will sound good, but I don't think one could say either is definitively correct. But both show three independently moving voices with either interpretation.

Ah, now it sounds good. You hear the melody as the prominent voice, the accompaniment part in the alto voice, and the bass line underneath. Although the notation is more complicated, it serves even the beginning player better than the shorthand version.

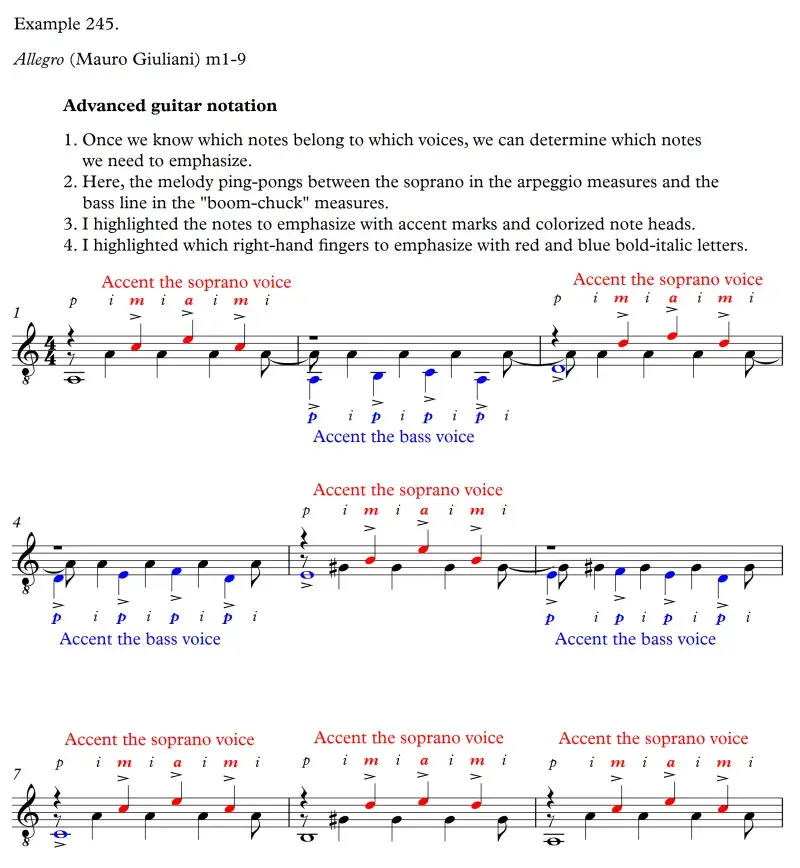

Sometimes it takes some detective work to find the melody in a song. Here is the second example from the beginning of this article where I asked, "Where is the melody?" It is a beginning study by Mauro Giuliani called Allegro. Giuliani notates it in his conventional guitar shorthand style. Example #243:

Hmm. On paper, it looks like measures of arpeggios alternating with "boom-chuck" measures. But when you play it, you realize more is going on. The notes within the arpeggios split into three voices, and the notes of the "boom-chuck" measures divide into two voices, like this. Example #244:

On a practical level, now we know which notes we need to emphasize. The melody jumps from the soprano voice in the arpeggio measures to the bass voice in the "boom chuck" measures. To play the passage correctly, we need to practice it like this. Example #245:

If you did not analyze the piece, you would probably practice playing all the notes at the same volume level, which is totally wrong. You need to know at the very least where the melody lines are to practice the song correctly!

SUMMARY

We took a deep dive into voices, their terminology, and notation. We learned:

- How the concept of voices originated with four-part harmony and vocal choirs

- How even instrumental pieces divide into voices and parts

- How to determine which notes belong to which voice

- That music moves in two dimensions: vertical and horizontal

- Two systems of guitar notation: the abbreviated shorthand notation and advanced notation

- We learned the advantages and disadvantages of both systems

- How to decipher the internal rhythms within each independently moving voice.

- That pieces with two or more voices with independently moving parts sound best on solo guitar

- How to find the melody in easy pieces

The ability to find the voices in a piece or determine which notes belong to which voices will improve over time with experience. Sometimes, there can be different interpretations of the voice leading with no clear-cut correct answer, especially in guitar music.

DOWNLOADS

1. Download a PDF of the article with links to the videos. Depending on your browser, it will download the PDF (but not open it), open it in a separate tab in your browser (you can save it from there), or open it immediately in your PDF app.

Download the PDF: HOW TO LEARN A PIECE (SONG) ON THE CLASSICAL GUITAR Part 10 with embedded video and audio clips.