Tips on Playing Bach's Bourree, BWV 996

"Douglas who?"

Douglas Niedt is a successful concert and recording artist and highly respected master classical guitar teacher with 50 years of teaching experience. He is Associate Professor of Music (retired), at the Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City and a Fellow of the Henry W. Bloch School of Management—Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

Doug studied with such diverse masters as Andrés Segovia, Pepe Romero, Christopher Parkening, Narciso Yepes, Oscar Ghiglia, and Jorge Morel. Therefore, Doug provides solutions for you from a variety of perspectives and schools of thought.

He gives accurate, reliable advice that has been tested in performance on the concert stage that will work for you at home.

PURCHASE AN ALL-ACCESS PASS

TO THE VAULT OF CLASSICAL GUITAR TECHNIQUE TIPS

"Hello Mr Niedt,

My name's Gretchen, and I'm so happy I purchased an All-Access Pass to the Vault. I love your awesome technique tips. I'm amazed how much I have improved my playing.

Thank you!"

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR PROVEN STRATEGIES

THAT WILL MAKE YOU A BETTER GUITARIST?

Check out the game-changing tips in my Vault—I promise they will kick your playing up to the next level.

Purchase an All-Access Pass to the Vault.

It's a one-time purchase of only $36!

You receive full access to:

- Over 180 technique tips in The Vault.

- Special arrangements of Christmas music

- Arrangement of the beautiful Celtic song, Skellig

- Comprehensive guide, How to Master the Classical Guitar Tremolo

All that for a one-time payment of only $36. Take me to the page to Purchase an All-Access Pass

Tips on Playing Bach's Bourree, BWV 996

By Douglas Niedt

Copyright Douglas Niedt. All Rights Reserved.

This article may be reprinted, but please be considerate and give credit to Douglas Niedt.

When you play a piece containing two or more distinct parts, especially one in counterpoint, it can be difficult to hear how well you are playing voices other than the upper one. We tend to focus on what we are familiar with, usually that upper voice. Many guitarists pay scant attention to the other voices and have no idea how well or poorly they are playing them. For instance, are you playing the middle or lower voice smoothly or chopping off notes that should connect? Are the inner rhythms correct? Are you rushing some of the notes in a voice? Are you cutting off notes that should ring or letting notes ring that you should damp? When you practice a contrapuntal piece, you must be aware of all these items.

The best way to do this is to practice each voice by itself. In the case of pieces in three or four voices, we can also practice pairs of voices. Finally, we can apply the practice tools we have already learned about to make the interactions of the voices crystal clear.

We will begin with an example most guitarists play or are familiar with—the Bourrée from Lute Suite No. 1 BWV 996. By the way, I notated the ornament in measure seven as a cross-string trill. Example #302:

A conventional left-hand fingering might look like this. Example 303:

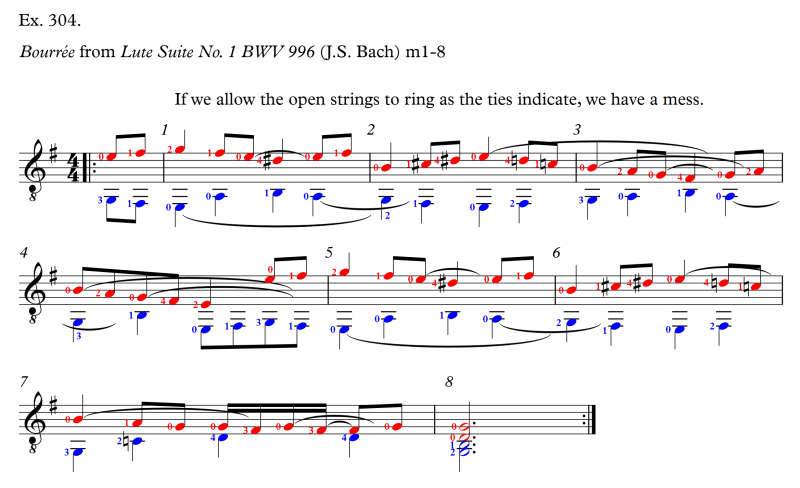

Remember that counterpoint consists of two or more LINES moving independently. You will recall our discussion that when we play a melody, we have a choice of playing it as a pure line (only one note rings at any given moment), a campanella where all the notes ring together as much as possible, or anything in between. In a contrapuntal piece, it is essential that the melody or voice be a pure line. When we allow notes to ring past other notes in the same voice, it implies a new voice. We don't want that to happen. In this conventional fingering, if we allow the open strings to ring, we end up with a mess. Example #304:

Listen to the confusion when I play both voices and allow the open strings to ring.

Voices ringing together, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

The most efficient way to zero in on the problems (and hear them) is to practice each voice separately. First, let's fret both voices but pluck only the soprano (upper) voice. Without any string damping, the open strings ring across the other notes in the soprano voice. This destroys the linear or horizontal dimension of the music. Example #305:

Listen to the mess I create in the passage by allowing the open strings in the soprano voice to ring.

Allowing open strings to ring in the soprano voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

But, I can make the upper voice a pure line if I apply string damping. Example #306:

Now listen to how clean the upper line sounds when I damp the open strings.

Damping the open strings in the soprano-voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Now let's follow the same process with the bass voice. Fret both voices but pluck only the bass (lower) voice. Without any string damping, the open strings ring across the other notes in the bass voice. Again, this destroys the linear or horizontal dimension of the music. Example #307:

Listen to the mess I create in the passage by allowing the open bass strings to ring.

Allowing open strings to ring in the bass voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

But, I can make the lower voice a pure line if I apply string damping. Example #308:

Now listen to how clean the bassline sounds when I damp the open strings.

Damping the open strings in the bass voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

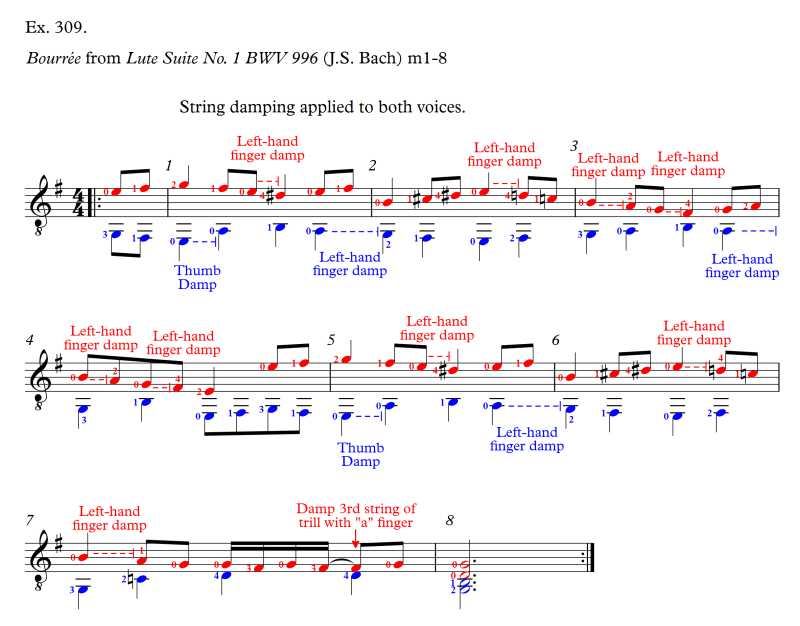

Once I master the string damping in each voice, I can put the two voices together and apply the damping. Now, I'm playing two pure lines, and the counterpoint is clear. Example #309:

On a side note, if you can avoid open strings, you can eliminate some string damping. That may be a good choice for intermediate players to make a passage easier to play. However, for advanced players, the sound should always come first. If a note sounds better open, play it open and use damping. Don't play it closed just to make it easier.

Listen to me apply string damping to the open strings in both voices of the Bach Bourrée.

Damping the open strings on both voices, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Here is a very simple way to check how you are playing individual voices in a piece.

When you work on a piece that contains two or more distinct parts, especially one in counterpoint, it can be difficult to hear how well you are playing a subsidiary part. We tend to focus on what we are familiar with. Here is a very simple way to check how you are playing individual voices in a piece.

A brief explanation:

The term "voices" (also called "lines") means the parts of the song. It comes from choir terminology: the upper voice (highest in overall pitch range) is the soprano voice or soprano part (often the melody, therefore also referred to as the melody line or upper voice); the lowest voice is the bass voice or bass part (the bass line or lower voice).

If a piece has more than two parts, the part directly below the sopranos is the alto voice or alto part or alto line (in choirs it is sung by females). The part directly above the basses is the tenor voice or tenor part or tenor line (in choirs it is sung by males). Therefore, a choir piece with the assignation SATB means it is for four voices--in descending order: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass.

In guitar notation, the stems of the noteheads of the soprano and alto usually go up and those of the tenors and basses go down so you can tell which part a note belongs to.

The Bourrée:

Let’s look at the Bourrée (or Bourée) from Lute Suite No. 1 (BWV 996). Incidentally, BWV is an abbreviation for Bach Werke Verzeichnis which means Bach Works Index. It is an index that numbers the complete works of Bach.

When playing the Bourrée, most players tend to focus on the upper voice and don’t really listen closely to the lower voice. After all, we know how the upper voice goes and can probably sing it from memory.

But what about the lower voice? Can you sing it from memory? Do you really know how it goes? Probably not. Even if you look at the music, you may not be able to sing it. Or if you play through the piece, can you sing the lower voice as you play both parts? Many people can't, and that is a real problem.

If you can't sing the lower voice, you probably aren't really listening to it when you practice. You probably have little idea as to how well or poorly you are playing it. Are you playing it smoothly? Are you connecting the notes or chopping them up? Are you allowing notes to ring together that should be muted? This is a voice, a bass line. Therefore only one note should be allowed to ring at a time.

It is in these types of situations that "The Old Kleenex Trick" comes in handy.

HOW TO USE "THE OLD KLEENEX TRICK" ON THE BACH BOURRÉE

First, to get a better idea of what you are trying to accomplish, watch this video:

To really hear how you are playing the lower voice, try this. Fold a piece of Kleenex (I use the term generically, you can use any brand) several times and then insert it under the treble strings around the 15th to 19th fret to mute them. Play the Bourrée normally, fingering and plucking both voices. Because the Kleenex is muting the treble strings, you will hear only the lower voice, and you will hear it with crystal-clear clarity.

Watch this demonstration.

You can reverse the procedure, stuffing the Kleenex under the bass strings in order to clearly hear the upper voice.

Watch me demonstrate.

The trick works with varying degrees of success depending on how the parts divide themselves among the strings. And you might have to adjust the Kleenex to cover different sets of strings for different sections or measures of the same piece. Nevertheless, it is a very practical and helpful way to clearly hear exactly how you are playing the individual parts or voices of a piece. Very LOW-tech, but it works!

HOW TO USE REFLEX PRACTICE (or speed bursts)

TO LEARN THE ORNAMENT IN MEASURE #7 OF THE BACH BOURRÉE

At the end of the first part of the Bourée (or Bourrée) from J.S. Bach's Lute Suite I (BMV 996) is a measure with a mordent:

Example #2

One way to play the ornament is to use a trill instead. It is more difficult to play but I think it sounds better:

Example #3

Some players may prefer to use this right-hand fingering to execute the trill:

Example #4

Both are good fingerings. Which one should you use? The fastest way to find out is with reflex practice (or speed bursts). You will know within minutes which fingering will work best for you. Watch this video to learn how to master the trill using reflex practice (or speed bursts).

Be sure to watch the video on full screen. Click the symbol to the right of "HD" in the lower right-hand corner after the video begins playing. Hit escape "ESC" on your keyboard to return to normal viewing.

Anchor Fingers Can Make the Ornament in Measure #7 of the Bach Bourrée Easier and More Secure

Anchor fingers can facilitate the secure and clear execution of ornaments. Anchors' secondary benefit of string damping makes ornaments sound cleaner. Here is a cross-string trill at the end of the first section of J.S. Bach's Bourree from Lute Suite No. 1 (BWV 996). The use of anchor fingers makes execution easier and mutes an unwanted open G at the end of the trill:

Watch this video demonstrating how to use an anchor finger to play the trill.