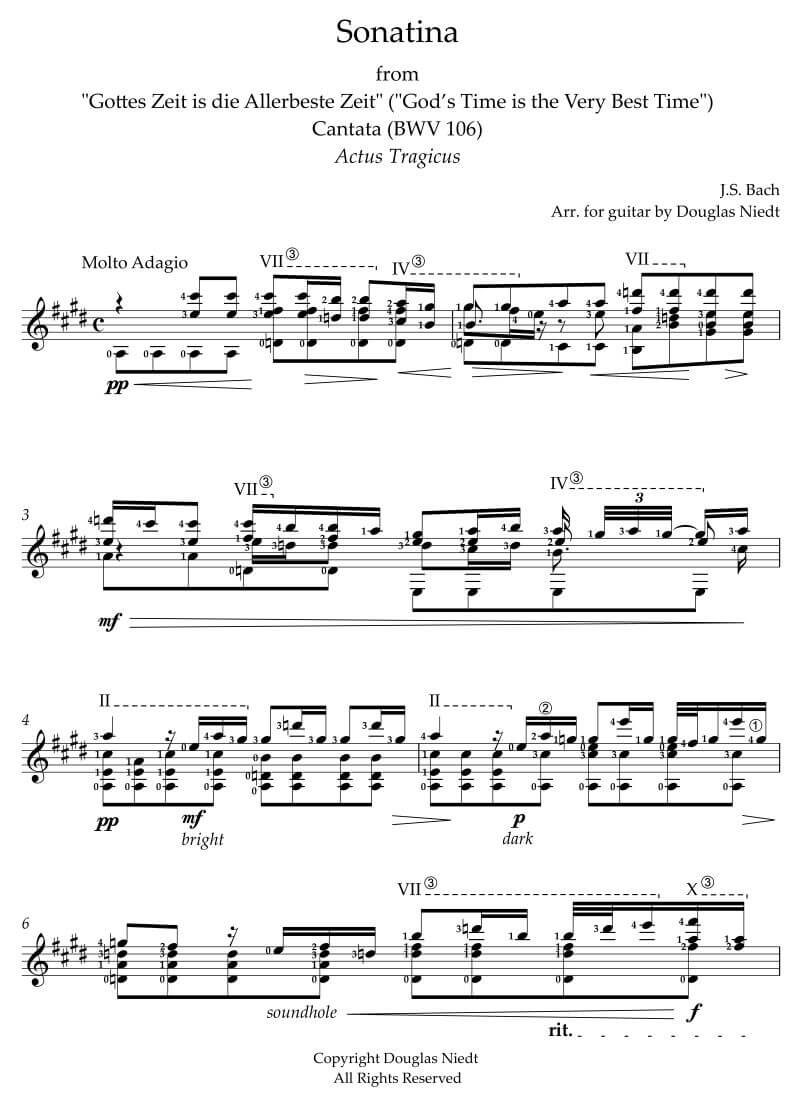

"SONATINA" by J.S. Bach

(transcribed for the guitar by Douglas Niedt)

“Twenty of the most heart-stopping bars in all of Bach’s works.”

(Sir John Eliot Gardiner)

The "SONATINA" is the prelude to Johann Sebastian Bach's Cantata, Actus Tragicus (BWV 106)

THE "SONATINA" SHEET MUSIC PACKAGE IS FREE!

This is a digital download.

The "Sonatina" sheet music package includes:

- Douglas Niedt's transcription for guitar in standard notation

- Douglas Niedt's transcription for guitar in standard notation plus TAB

- Doug's audio recording

- The video displaying the score as Doug plays the piece

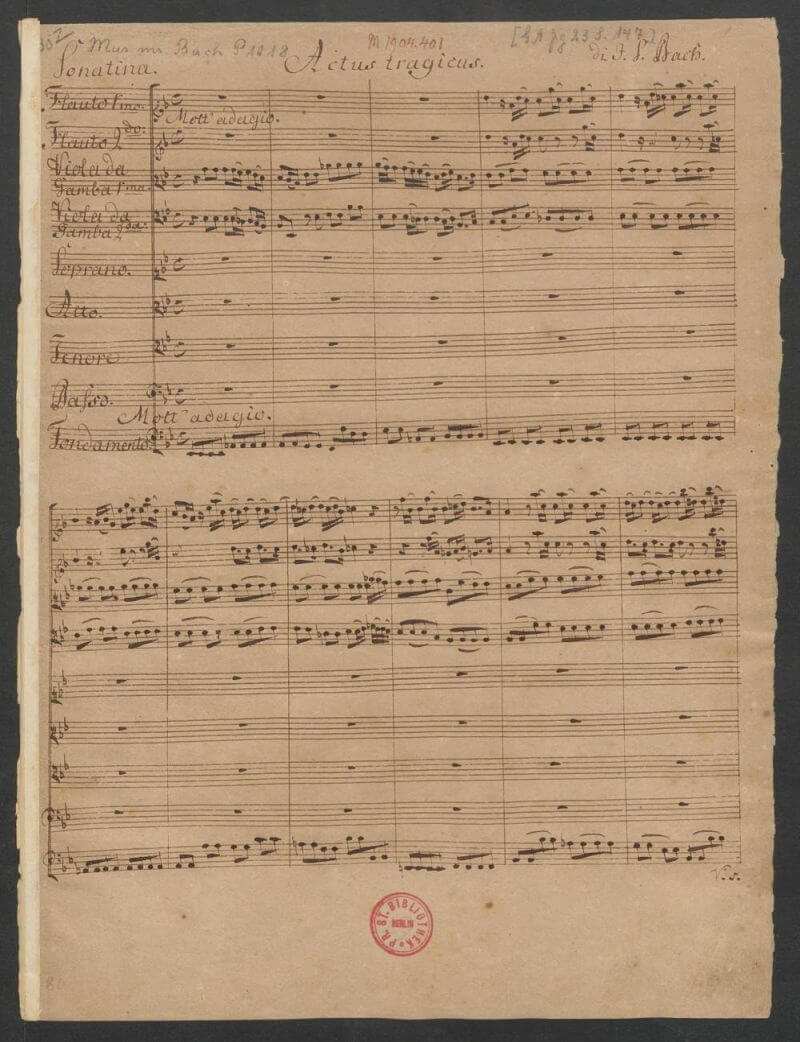

- The manuscript copy of the entire Cantata

- The Neue Bach-Ausgabe copy of the entire Cantata, edited by Ryuichi Higuchi

Click the gift package or the link below to download the zip file containing ALL of the above items. Save whichever items you want to your computers and devices.

Douglas Niedt's transcription of "Sonatina"

Note that this transcription is for intermediate and advanced guitarists.

“Twenty of the most heart-stopping bars in all of Bach’s works.” (Sir John Eliot Gardiner)

The “Sonatina” is the first piece or prelude of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Cantata (BWV 106), “Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit” (“God’s Time is the Very Best Time"), also known as Actus Tragicus. “God’s Time is the Very Best Time" is an early sacred cantata composed by Bach at the age of 22 in Mühlhausen, Germany, between 1707 and 1708, intended for a funeral.

In the opening “Sonatina,” marked molto adagio, two alto recorders mournfully echo each other over a sonorous background of viola da gambas and continuo. In modern performances, the continuo part is often performed by an organ or lute.

The piece begins in a tranquil, contemplative mood but, as it proceeds, evokes intense passion and loss. It gradually slows to a warm and hushed ending, illustrating an important metaphor of the Cantata overall: relating death to a peaceful and welcoming sleep.1

The “Sonatina” mourns and reflects upon the soul and character of the departed. It is soul-wrenching but also very, very beautiful and fragile. Conductor and Bach specialist Sir John Eliot Gardiner calls it “Twenty of the most heart-stopping bars in all of Bach’s works.”

The Cantata, “Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit” (“God’s Time is the Very Best Time"), also known as Actus Tragicus, is an early sacred cantata composed by Johann Sebastian Bach at the age of 22 between 1707 and 1708 in Mühlhausen, Germany. It was intended to be performed at a funeral.

The religious text expresses Christian belief in eternal life, contrasting eternity (“God’s time”) with our temporal, everyday life on earth. Hence the title, “God’s Time is the Very Best Time.”

Although Bach's manuscript is lost, the work is agreed to be one of the earliest Bach cantatas, probably composed during the year he spent in Mühlhausen, Germany in 1707-1708 as organist of the Divi Blasii church. Various funerals known to have taken place at this time have been proposed as the occasion for the composition, for example, that of his uncle Tobias Lämmerhirt from his mother's family, who died in Erfurt on August 10, 1707, and that of Adolph Strecker, a former mayor of Mühlhausen, whose funeral was September 16, 1708.

The earliest surviving manuscript, in the hand of Christian Friedrich Penzel, was copied in 1768 after Bach's death. It introduced the title Actus Tragicus. The cantata was published in 1876 as part of the first complete edition of Bach's works: the Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe (Bach Society Edition), edited by Wilhelm Rust.

The combination of instruments Bach uses in the Cantata has been described as idiosyncratic, exceptionally beautiful, meaningful, and unusual. The violins are conspicuous by their absence, but there are two recorders, continuo, and two viola da gambas, which provide a soft, comforting, and sometimes almost heavenly sound. The recorders seem to symbolize earthly suffering with their sharp seconds and unisons.

The text of the Cantata consists of different Bible passages from the Old Testament and New Testament, as well as individual verses of hymns by Martin Luther and Adam Reusner, which all together refer to preparation for death and dying. The cantata has two distinct parts. The first part presents the view of death from the Old Testament (everyone must die), and the second part presents the view of death from the New Testament (redemption). The form is, therefore, symmetrical, and each part is a similar length.

Although movements are marked by tempo changes, occasional key changes, meter changes, and double bar lines (not thick, bold bar lines, however, as at the end of a work), Cantata 106 is a continuous work. Bach helps create a more seamless effect by occasionally resolving the cadence of one section at the downbeat of another, thus blurring the beginnings and endings of traditional movements.2

It is a work of such depth and intensity that one can scarcely avoid speculating that the deceased, for whose internment it was composed, had some personal connection with the twenty-two-year-old composer. Or perhaps it simply struck a chord that reminded him of the death of his own parents, scarcely more than a dozen years previously. But whatever the personal impact the occasion might have had on him, there is no disputing the profundity that the emerging composer managed to elicit from the minimal lines of conventional text.3

James R. Gaines, in Evening in the Palace of Reason: Bach Meets Frederick the Great in the Age of Enlightenment 4, writes, “The greatness of great music is in its ability to express the unutterable…The Actus Tragicus is almost unspeakably beautiful.” This Cantata ranks among Bach's most important works. The Bach scholar Alfred Dürr called the Cantata "a work of genius such as even great masters seldom achieve...The Actus Tragicus belongs to the great musical literature of the world.”

Sir John Eliot Gardiner’s thoughts

on the Cantata, Actus Tragicus

This Cantata (BWV 106) is a truly extraordinary piece of music. It is one of Bach’s very early surviving works, written when he was only 22. BWV 106, better known as the Actus Tragicus, is one of my most favorite pieces. For the moment, let's just forget that Bach ever went to Leipzig, that he became Thomas cantor and stayed there for 27 years. Let’s also forget the great music that he composed there—the St. John’s Passion, the St. Matthew Passion, and two-thirds of his church cantatas. Because on the basis of this one work alone, he deserves recognition as one if not the greatest of all composers of religious music.

So, what do we know about this piece, and what makes it so special? Well, to start with, there is no autograph score, and it wasn't discovered until 16 years after his death, and then, in a copied score. But it was the first of his cantatas to be published as part of the Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe (Bach Society Edition), edited by Wilhelm Rust in 1867. From its text, it's clear that this is no regular Sunday or festive cantata like many of his others.

It was written for a funeral, but we don't know whose. And like so many of his works on the subject of death, it's never morbid or saccharine. On the contrary, it's serene and basically optimistic. Bach himself knew a thing or two about death, grief, and consolation, having lost both his parents before his 10th birthday. And he was forced to dig deep and become self-reliant.

And above all, this music is consoling. Ask anyone who's been in need of solace when coping with grief. It doesn't matter if they're Christian or agnostic or even atheist—if they've somehow turned to or been directed to Bach and heard a piece like the Actus Tragicus, the chances are they found inspiration and comfort. And the thing is that although the Cantata 106 is crammed with complex, challenging Lutheran theology, it's written by a very human, human being and the music reveals chinks in his armor plating through which we can glimpse the vulnerability of a regular person's struggles with a regular person's doubts and fears.

Right from the start, Bach draws us into a world of magical sounds that is very different from his other cantatas due to its spare scoring— just two alto recorders and two viola da gambas and continuo. The opening “Sonatina” consists of twenty of the most heart-stopping bars in all of Bach’s works. The gambas begin the piece with yearning dissonances. Bach creates a ravishing soundscape where the two recorders entwine, slipping in and out of unison and swapping adjacent notes; it's a technique known as “battement,” literally beating against each other—and there's nothing quite like this in any other 18th-century music I've ever come across, though it's a device used quite often in contemporary music. Note by Douglas Niedt: Unfortunately, due to the constraints of the guitar fingerings, I was unable to imitate the effect in my transcription for the guitar.

And then the drama unfolds. The cantata is arranged symmetrically in two parts. Part One centers mainly on Old Testament quotations—four short interlocking movements stressing the need to prepare for death. It's God who sets the clock, so set your house in order and observe the law and the covenant because man, you'll have to die.

Part Two is a bit less severe and centers on the New Testament. Bach begins with, “Into your hands I commit my spirit; you have redeemed me, Lord, faithful God.” To which Jesus replies as he did to the thief crucified next to him, “Today you will be with me in paradise.” Bach continues, “With peace and joy I now depart in God’s will...As God had promised me: death has become my sleep.”

Perhaps the easiest way to grasp the overall structure of this cantata is to picture it as an inverted isosceles triangle. Part One begins on the top left diagonal, moving downwards to the actual moment of death. Bach marks this with silence— an empty bar with a fermata over it. And then comes the gradual ascent up the right-hand diagonal with its comforting New Testament message that death is just a sleep.

I find the most touching moment in this Cantata is when the music bottoms out at the end of Part One, just before that silent bar, which is so mysterious. The three lower voices have been hammering out the ancient law and covenant in a fugue, while the solo soprano above them has all the while been making impassioned pleas to Jesus to come and save her. But gradually, the fugue peters out, and the instruments playing the chorale tune drop out, one by one, leaving the soprano alone and unsupported— her voice trailing away in a fragile arabesque, a bit like a butterfly, utterly magical.

Watch the Netherlands Bach Society

perform the entire cantata.

The magical moment Sir John Eliot Gardiner describes above is at 10:36 to 12:05.

REFERENCES

1Michael Beattie, Emmanuel Music

3Julian Mincham, The Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach, A Listener and Student Guide

4James R. Gaines, Evening in the Palace of Reason: Bach Meets Frederick the Great in the Age of Enlightenment