THE TRILL:

Its notation, execution, and the challenges of historical interpretation

"Douglas who?"

Douglas Niedt is a successful concert and recording artist and highly respected master classical guitar teacher with 50 years of teaching experience. He is Associate Professor of Music (retired), at the Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City and a Fellow of the Henry W. Bloch School of Management—Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

Doug studied with such diverse masters as Andrés Segovia, Pepe Romero, Christopher Parkening, Narciso Yepes, Oscar Ghiglia, and Jorge Morel. Therefore, Doug provides solutions for you from a variety of perspectives and schools of thought.

He gives accurate, reliable advice that has been tested in performance on the concert stage that will work for you at home.

PURCHASE AN ALL-ACCESS PASS

TO THE VAULT OF CLASSICAL GUITAR TECHNIQUE TIPS

"Hello Mr Niedt,

My name's Gretchen, and I'm so happy I purchased an All-Access Pass to the Vault. I love your awesome technique tips. I'm amazed how much I have improved my playing.

Thank you!"

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR PROVEN STRATEGIES

THAT WILL MAKE YOU A BETTER GUITARIST?

Check out the game-changing tips in my Vault—I promise they will kick your playing up to the next level.

Purchase an All-Access Pass to the Vault.

It's a one-time purchase of only $36!

You receive full access to:

- Over 180 technique tips in The Vault.

- Special arrangements of Christmas music

- Arrangement of the beautiful Celtic song, Skellig

- Comprehensive guide, How to Master the Classical Guitar Tremolo

All that for a one-time payment of only $36. Take me to the page to Purchase an All-Access Pass

THE TRILL:

Its notation, execution, and the challenges of historical interpretation

By Douglas Niedt

Copyright Douglas Niedt. All Rights Reserved.

This article may be reprinted, but please be considerate and give credit to Douglas Niedt.

PREFACE

The first thing you need to know when deciding how to play any ornament in pre-20th-century music is that there was no "common practice." The notation and execution of ornaments varied from country to country and composer to composer.

Written instructions from long ago or ornament tables (even by J.S. Bach) cannot overcome the general shortcomings of musical notation. Rigid rules, no matter where they come from, go against the very nature of ornaments—they were often improvised and, therefore, are too free to be tamed into regularity or taught by the book.

Descriptions of ornaments are only rough outlines, and many are contradictory. It's a jungle and very frustrating to try to figure out. There is simply no definitive solution to any ornament in a given situation. Therefore, be skeptical of everything I write from here on!

If you want a short answer to how to play an ornament, I say, "Do whatever you want. Do what makes the music sound best, and do what sounds best to you. In the end, that's what counts."

What is a Trill?

The trill (Italian Trillo, French Trille, German Triller) is a musical ornament consisting of a rapid alternation between the written principal note and an auxiliary note, either a half or whole step above the principal note.

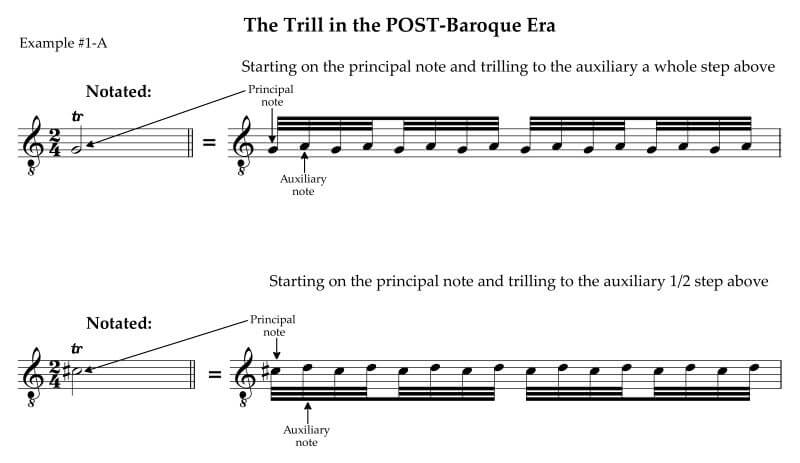

In POST-Baroque music, the consensus is that the trill begins on the principal note. (Note: there are exceptions.) Example #1-A:

However, in BAROQUE music, such as that by J. S. Bach, the consensus is that the trill begins on the upper auxiliary note. (Again, there are exceptions.) Example #1-B:

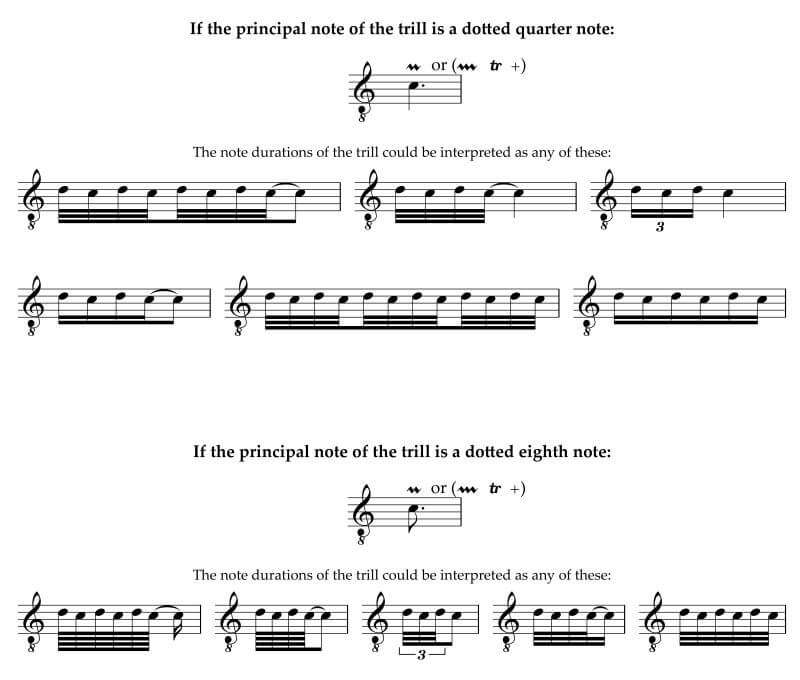

The duration of the notes of the trill varies according to the value of the principal note and the tempo of the passage. The final note of the trill can be a little longer in duration than the preceding notes. But in other instances, the trill may continue for the entire value of the note. The following examples are typical but not exhaustive. The minimum number of repetitions or "shakes" of the principal note is two, or a total of four notes sounding for the entire trill. Note that these are examples of Baroque trills that start on the upper auxiliary, not the principal note. Trills in later periods usually begin on the principal note. However, the possible durations of the notes of either trill will be the same. Example #2:

Notation of the Trill

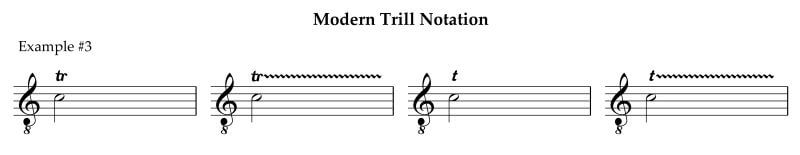

Today, a trill is indicated by the letters "tr" or "t" above the trilled note. The "tr" is sometimes followed by a horizontal wavy line. Example #3:

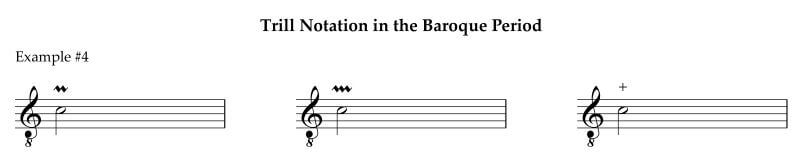

In the Baroque period, composers used a short horizontal zig zag or a longer horizontal zig-zag line to indicate a trill. Some composers indicated the trill with a "+" (plus sign) above or below the note. Example #4:

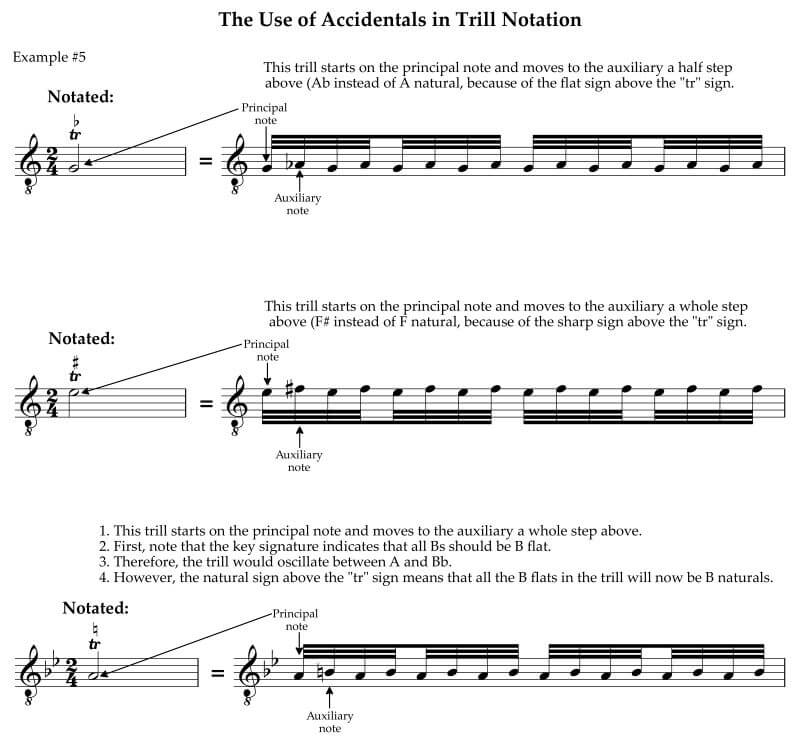

Composers could modify a trill by placing accidentals above the symbol. Example #5:

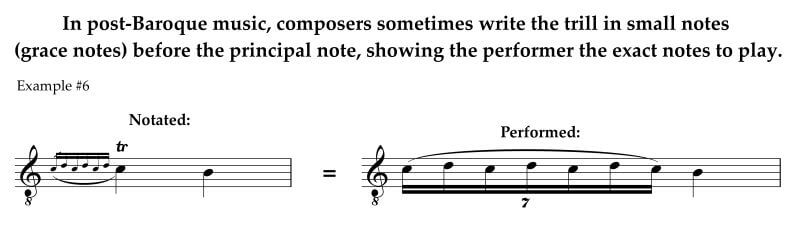

In post-Baroque music, composers sometimes write the trill in small notes (grace notes) before the principal note, showing the performer the exact notes to play. Example #6:

On Which Note Does the Trill Start?

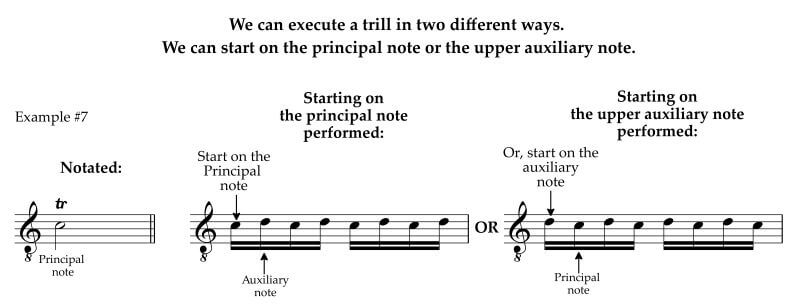

We can execute a trill in two different ways. We can begin with either the principal note or the auxiliary note. The auxiliary note is the note 1/2 or one whole step above the principal note. Example #7:

These two performance modes differ considerably in effect because the accent, which is always perceptible, however slight it may be, is given in one case to the principal note and the other to the auxiliary note. It is, therefore, essential to ascertain which of the two methods to use in any given case.

Various writers have discussed the question with much fervor. Most of the earlier masters, including C. P. E. Bach, Marpurg, and Türk, held that all trills should begin with the upper note, while later masters, such as Hummel, Czerny, and Moscheles, preferred to start on the principal note.

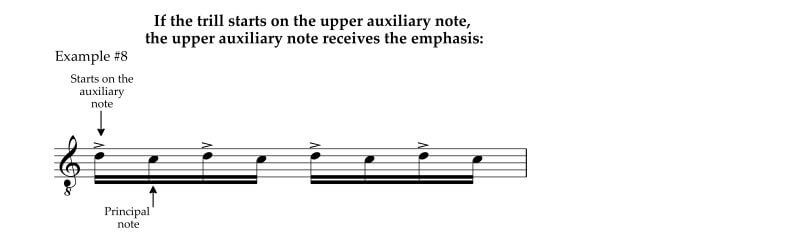

This diversity of opinion indicates two different views of the very nature and meaning of the trill. In the Baroque period, musicians thought of the trill as a series of appoggiaturas with their resolutions. German music critic, theorist, and composer Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg wrote, "The trill derives its origin from an appoggiatura and is, in fact, a series of descending appoggiaturas executed with the greatest rapidity." As such, the trill starts on the upper auxiliary note, and the accents and emphasis fall on the auxiliary note (the note 1/2 to a whole step above the principal note). Example #8:

Therefore, in Baroque music, trills usually start on the upper neighbor or auxiliary, often producing the effect of a harmonic suspension that resolves to the principal note. For example, if the principal note is C, the trill would begin on D (the upper auxiliary), not C (the principal note), and not B (the lower auxiliary).

Even though the general consensus is that in the Baroque era, the trill begins on the upper auxiliary note above the principal note, and that the trill always begins on the beat, there are exceptions to this. In the end, don't play by following "rules." Do what sounds best in each passage.

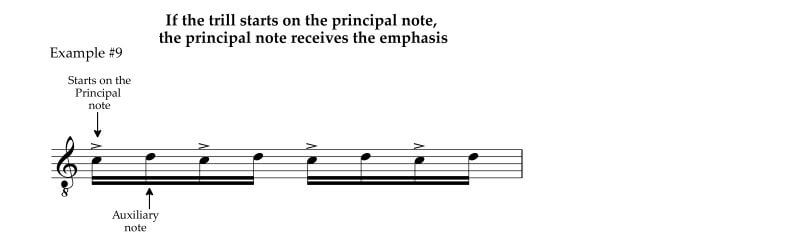

But writers and musicians in the post-Baroque era thought of the trill as a trembling or pulsation of the principal note; therefore, the trill starts on the principal note, and the accents and emphasis fall on the principal note. Example #9:

So, as we transition from the Baroque period into the Classical period, a gradual change of preference begins to take place until most musicians start their trills on the principal note. Such is the case with guitarists Dionisio Aguado, Fernando Sor, and Mauro Giuliani. Aguado writes out a table of trills in his New Guitar Method, all beginning on the principal note.

Therefore, in the Baroque period, starting the trill on the upper auxiliary note was almost always the preference. After the Baroque period, there was a gradual change of preference to starting trills on the principal note.

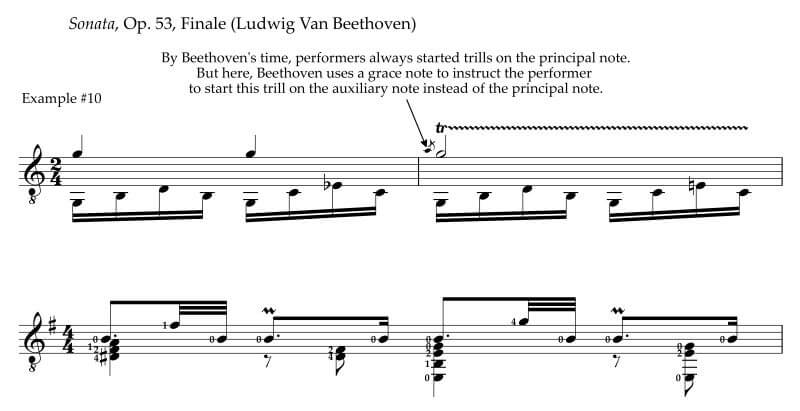

However, if a post-Baroque composer wanted the trill to start on the upper auxiliary, he could notate it with a grace note. Here is an example from Beethoven’s Sonata, Op. 53. Example #10:

How to Execute a Trill on the Classical Guitar

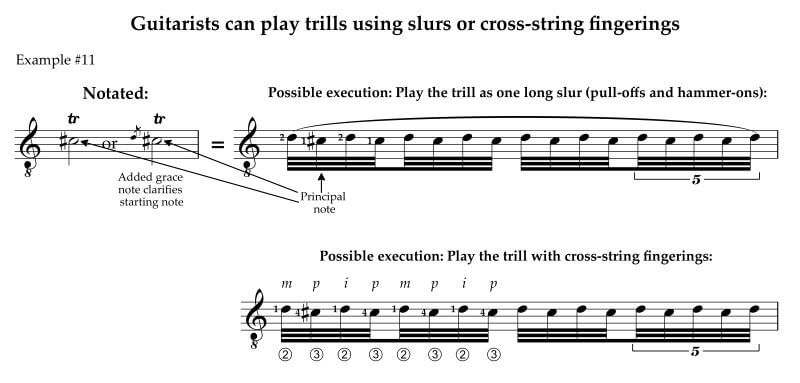

Trills (and many other ornaments) can be executed with slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs) or as cross-string ornaments. Example #11:

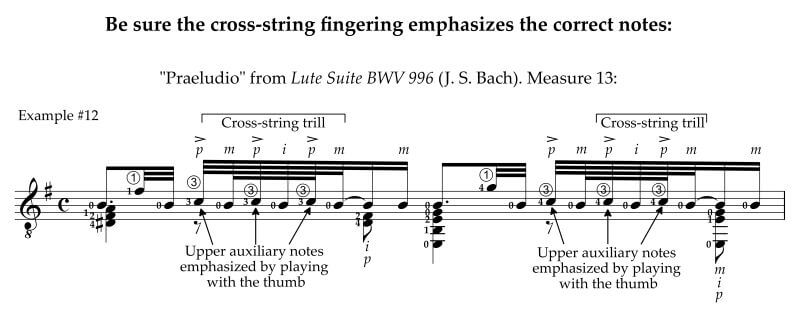

Whether the trill begins on the auxiliary note or the principal note has implications for the right-hand fingering of cross-string trills on the classical guitar. For example, suppose we are playing a piece by Bach, such as the “Praeludio” from Lute Suite BWV 996 and we begin a cross-string trill on the auxiliary note as in measure 13. In that case, we should consider placing the auxiliary note on a lower string and the principal note on a higher string so that we can use the thumb to play the auxiliary note with a heavier touch and the principal note with a finger using a lighter touch. This approach fulfills the theoretical idea discussed above that the emphasis on trills during the Baroque period should almost always be on the auxiliary note (the repeated appoggiatura). Example #12:

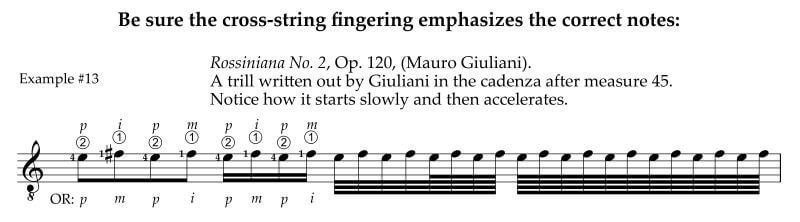

On the other hand, suppose we are playing a piece by Sor or Giuliani (post-Baroque music), and we begin a cross-string trill on the principal note. For example, in Giuliani’s Rossiniana No. 2, Op. 120, we have a written-out trill in the cadenza after measure 45. In that case, we should consider placing the principal note on a lower string and the auxiliary note on a higher string so we can use the thumb to play the principal note with a heavier touch and the auxiliary note with a finger using a lighter touch. This approach fulfills the idea that trills after the Baroque period should emphasize the principal note rather than the auxiliary note. Example #13:

There is no rule that determines the number of note alternations in a trill. The length of the principal note is the primary determining factor since there is more time to play more notes in a longer note than a short one. The overall tempo of the passage will also be a factor.

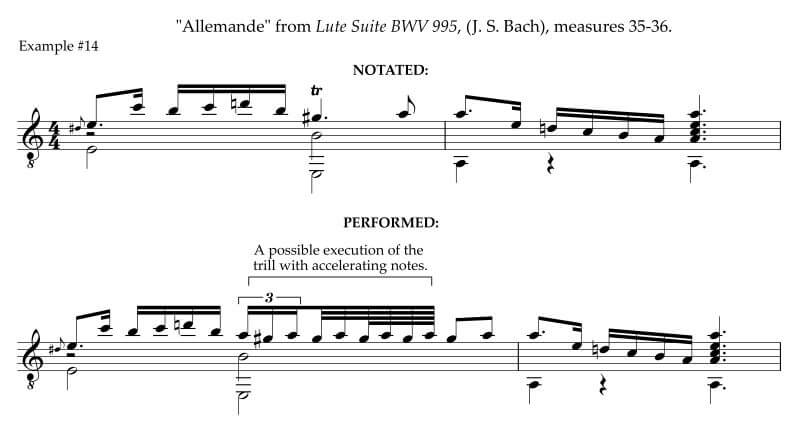

In many cases, the rate of the trill does not remain constant. Instead, depending on the passage and musical style, it can start slower and increase in speed to the final note. Such is the case in the preceding example by Giuliani. We can use the same approach for the trill in the "Allemande" from Lute Suite BWV 995, (J.S. Bach), measures 35-36. Example #14:

All of the various "rules" of how to play the trill, including the overall speed of the trill and whether that rate is constant or variable, can only be determined by considering the context in which the trill appears. The trill's properties will vary according to the passage's tempo, the length of the principal note, what precedes and follows the trill, what is happening in the other voices, and the desired effect. It is usually, to a large degree, a matter of opinion with no single "right" way of executing the ornament.

MODIFIED OR EXTENDED (COMPOUND) TRILLS

A composer can combine grace notes and ornaments to form a new combination. An example of this is compound trills. Here are several examples:

- Trill with termination (trill and mordent)

- Trill with an upper prefix (trill with turn from above)

- Trill with an upper prefix (turn from above) and termination (mordent)

- Trill with a lower prefix (trill with inverted turn from below)

- Trill with a lower prefix (trill with inverted turn from below) and termination (mordent)

- Mordent trill

- Slide trill

- Italian double trill

German composers began using compound trills imported from France in the early years of the 18th century. J. S. Bach was one of the first Germans to use compound trills systematically. He included them in his table of ornaments ("Explanation of various signs, intimating the way of gracefully rendering certain ornaments"), which he wrote for his son, Wilhelm Friederich. However, keep in mind that this table only applies to keyboard instruments. For other instruments, Bach writes out the various compound trills in regular notes or grace notes.

By the early 1800s, composers began to write out the notes of compound trills exactly how they wanted them to sound in regular-sized notes rather than with symbols or grace notes.

THE TRILL WITH TERMINATION

In his table of ornaments, J.S. Bach calls this a trillo und mordant. But the trill with termination goes by additional names as well:

- A trill with a suffix (the two added notes sometimes termed a nachschlag)

- A trill with closing notes

- A trill with mordent

The inclusion of the word "mordent" in some of the names refers to the final three notes of the ornament forming a descending mordent.

The Trill With Termination in the Baroque period

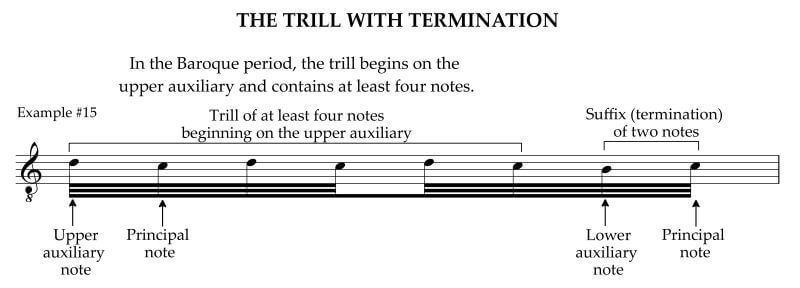

The Baroque-period trill with termination consists of a trill of at least four notes (beginning on the upper auxiliary of the principal note) and a suffix of two notes. The suffix is the auxiliary note below the principal note and, finally, the principal note. Example #15:

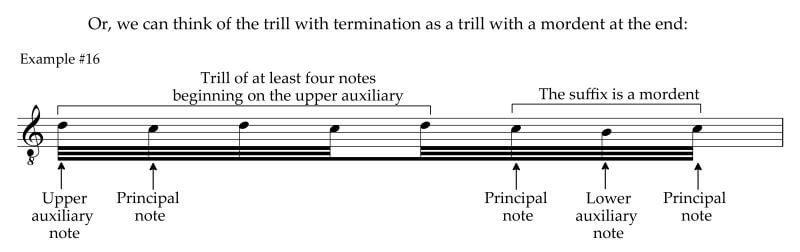

Or again, we can think of the ornament as a trill with a mordent as the suffix at the end. Example #16:

The post-Baroque Trill with Termination

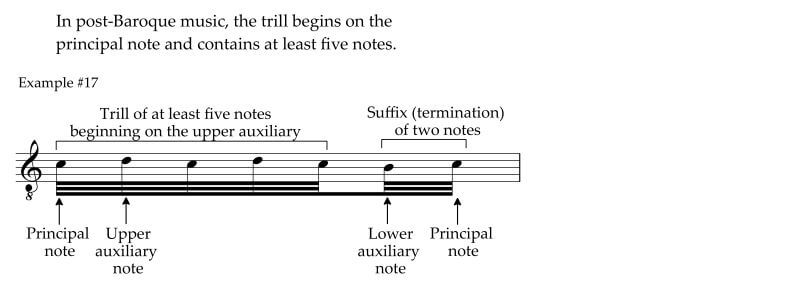

The post-Baroque trill with termination consists of a trill of at least five notes (beginning on the principal note) and a suffix of two notes. The suffix is the auxiliary note below the principal note and, finally, the principal note. Example #17:

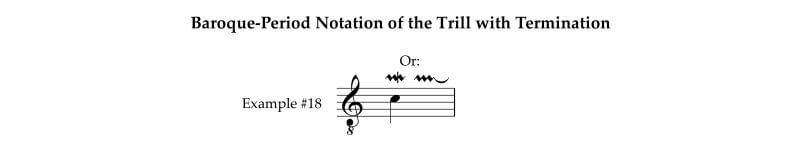

Notation of the trill with termination in the Baroque period

J.S. Bach notated this ornament as a long horizontal zig-zag line with a short vertical line passing through the zigzag right-of-center (the vertical line indicates the descending mordent at the end). Others notated it with a long horizontal zig-zag line ending with an equally long dipping curved line. Example #18:

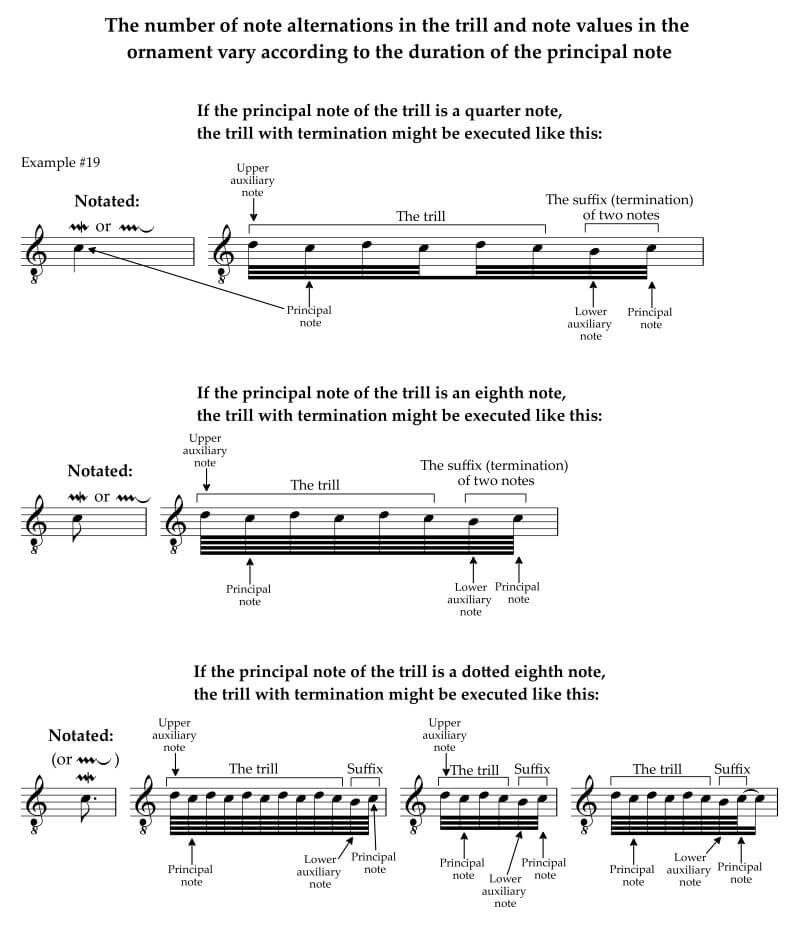

The number of note alternations in the trill with termination will vary. The length of the principal note is the primary determining factor since there is more time to play more notes in a longer note than a short one. The overall tempo of the passage will also be a factor. Here are examples of trills with terminations using principal notes of different lengths and various ways to execute them. Example #19:

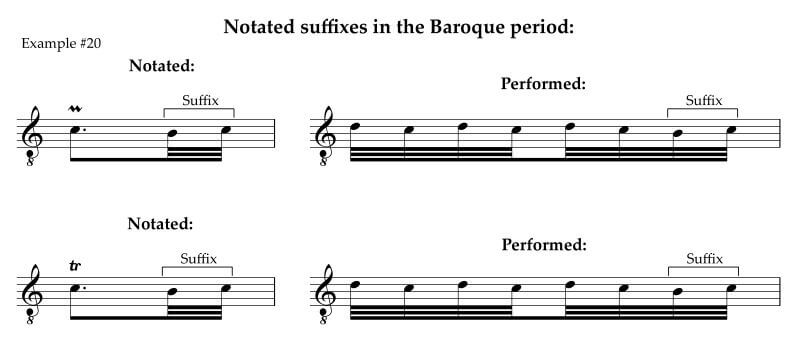

Or, in the Baroque period, the composer may use a zig-zag symbol without the vertical line through it (the basic symbol for a trill) or a "tr" symbol but write out the notes of the suffix. Note that the trill begins on the upper auxiliary note. Example #20:

Post-Baroque Notation of the Trill with Suffix

Or, in post-Baroque periods, composers used the "tr" symbol instead of the zig-zag symbols and wrote out the termination or suffix in full. Note that the trill begins on the principal note. Example #21:

THE TRILL WITH AN UPPER PREFIX

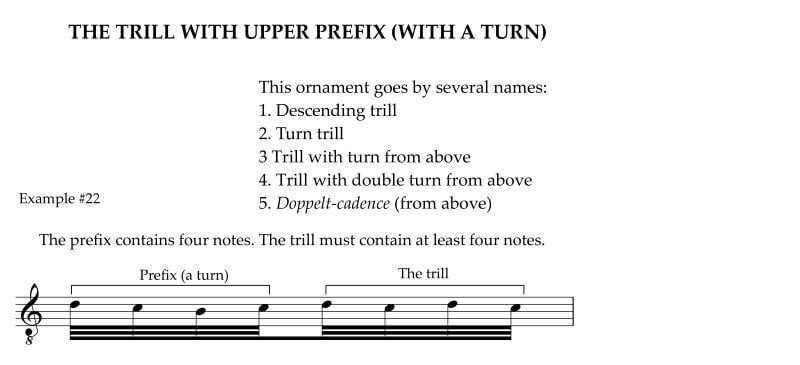

The trill with an upper prefix goes by several names:

- Descending trill

- Turn trill

- Trill with turn from above

- Trill with double turn from above

- Doppelt-cadence from above

This trill with an upper prefix consists of a prefix and a trill. The prefix, which is an ornament called a turn, consists of four notes: the auxiliary note above the principal note, the principal note, the auxiliary note below the principal note, and finally, the principal note. The prefix is followed immediately by a trill of at least four notes, beginning on the auxiliary note above the principal note. Example #22:

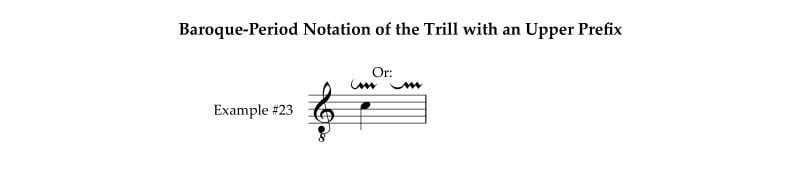

Notation of the trill with an upper prefix

J. S. Bach notated this ornament as a letter C-like curve connected to the beginning of a long horizontal zig-zag line. Others notated it as a curved dipping line connected to an equally long horizontal zig-zag line. Example #23:

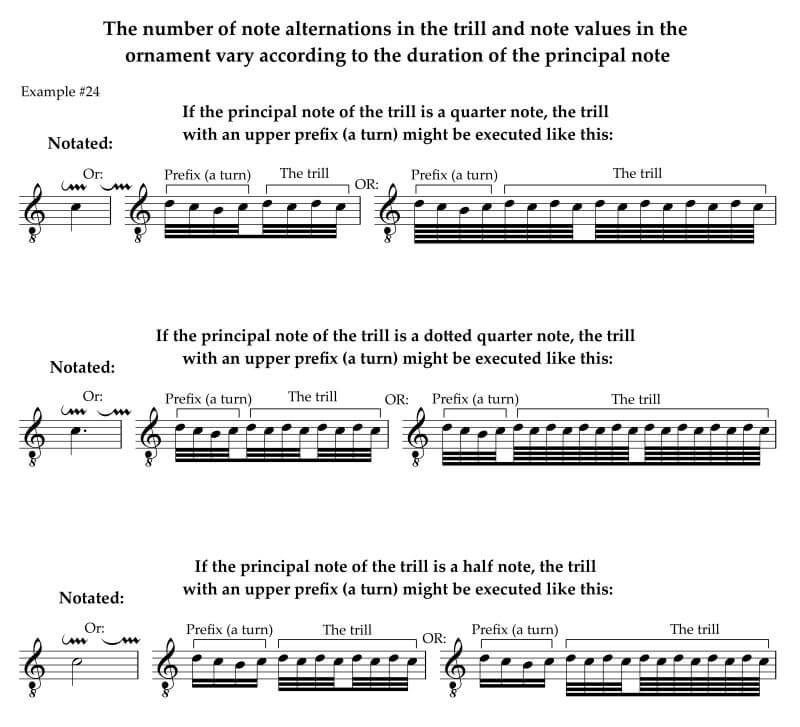

The number of note alternations in the trill with an upper prefix will vary. The length of the principal note is the primary determining factor since there is more time to play more notes in a longer note than a short one. The overall tempo of the passage will also be a factor. Here are examples of trills with an upper prefix using principal notes of different lengths and various ways to execute them. Example #24:

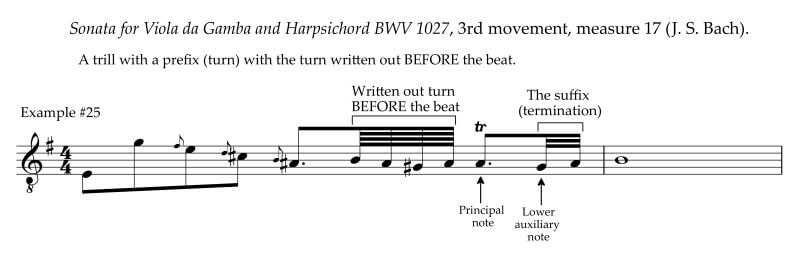

However, it is essential to note that while the above examples show the trill with an upper prefix (or trill with turn from above) as starting on the beat, there are many examples in J. S. Bach's music of them starting BEFORE the beat. Here is an example from Bach’s Sonata for Viola da Gamba and Harpsichord BWV 1027, 3rd movement, measure 17. Note that Bach writes out the turn and the suffix in regular-sized notes. Example #25:

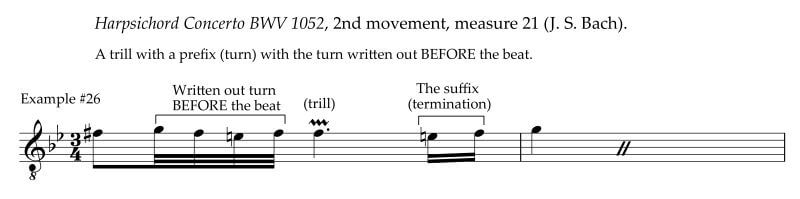

And here is another example from Bach’s Harpsichord Concerto BWV 1052, 2nd movement, measure 21. Again, note that Bach writes out the turn and suffix in regular-sized notes. Example #26:

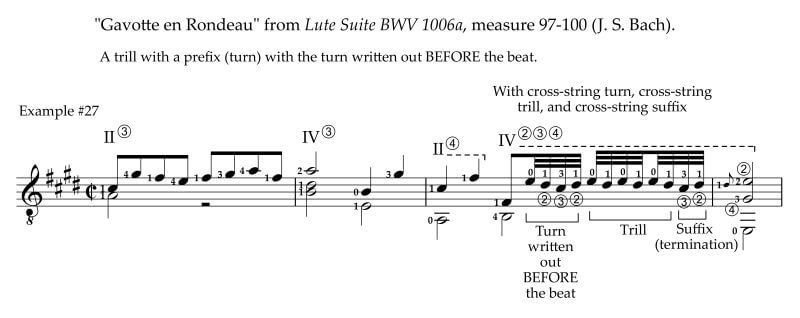

In measure 99 in the "Gavotte en Rondeau" from Lute Suite BWV 1006a by J.S. Bach, we have the opportunity to insert a trill. Although no trill is indicated in the original music, it was common practice to insert trills at cadences. In this case, I show an example of an added trill with a turn and suffix. As in Bach’s examples above, musically, it sounds best to begin the turn BEFORE the beat. Example #27:

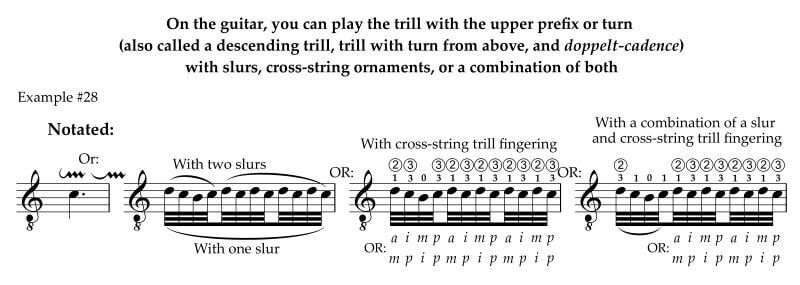

Guitarists can execute the trill with the upper prefix (also called a descending trill, trill with turn from above, and doppelt-cadence from above) with slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs), cross-string ornaments, or a combination of both. Example #28:

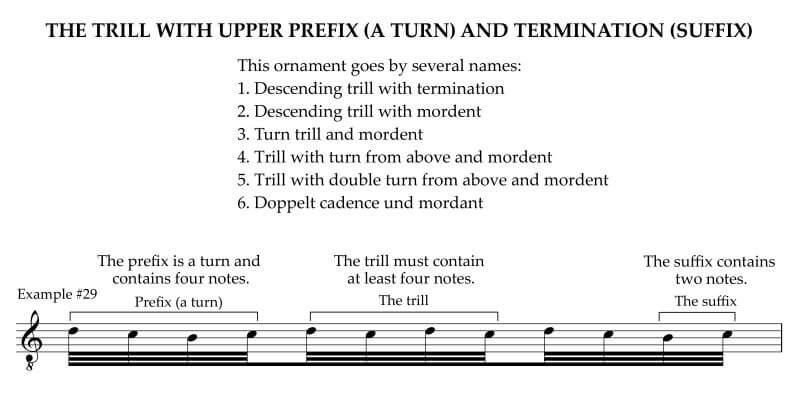

The trill with an upper prefix and termination

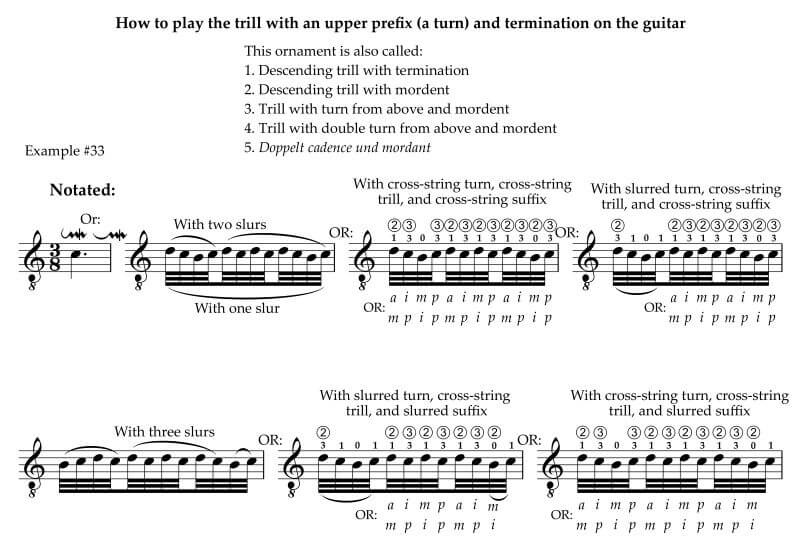

The trill with an upper prefix and termination goes by several names:

- Descending trill with termination

- Descending trill with mordent

- Turn trill and mordent

- Trill with turn from above and mordent

- Trill with double turn from above and mordent

- Doppelt cadence (from above) und mordant

The inclusion of the word "mordent" in some of the names refers to the final three notes of the ornament forming a descending mordent.

The trill with an upper prefix and termination consists of three parts: the upper prefix, the trill, and a suffix or termination. The ornament starts with a prefix, which is an ornament called a turn. It consists of four notes: the auxiliary note above the principal note, the principal note, the auxiliary note below the principal note, and finally, the principal note. The prefix is followed immediately by a trill of at least four notes, beginning on the auxiliary note above the principal note. The termination is a suffix. The suffix is the auxiliary note below the principal note and, finally, the principal note. Some writers call the suffix a nachschlag. Example #29:

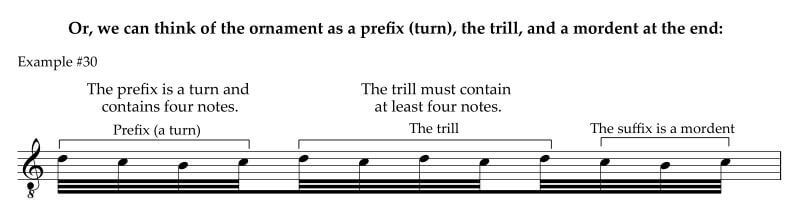

Or again, we can think of the ornament as starting with an upper prefix (turn), then the trill itself, and finally, a mordent as the suffix at the end. Example #30:

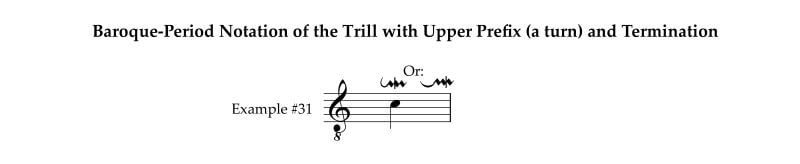

Notation of the trill with an upper prefix (turn) and termination

J. S. Bach notated this ornament as a letter C-like curve connected to a long horizontal zig-zag line with a short vertical line passing through the zig-zag line right-of-center (the short vertical line indicates the descending mordent at the end). Others notated it as a curved dipping line connected to an equally long horizontal zig-zag line. Again, the horizontal zig-zag line has a short vertical line passing through it right-of-center to indicate the mordent at the end. Example #31:

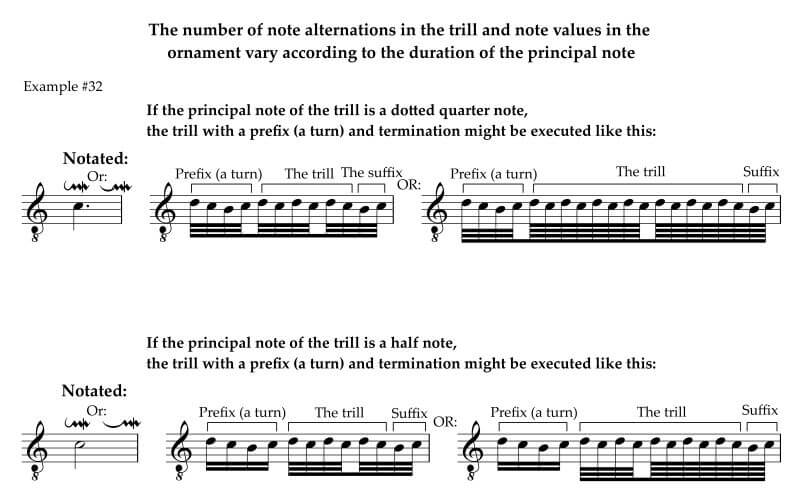

The number of note alternations in the trill with an upper prefix and termination will vary. The length of the principal note is the primary determining factor since there is more time to play more notes in a longer note than a short one. The overall tempo of the passage will also be a factor. Here are examples of trills with a prefix using principal notes of different lengths and various ways to execute them. Example #32:

However, it is essential to note that while the above examples show the trill with a lower prefix (a trill with a turn from above) starting on the beat, there are many examples in Baroque music of them starting BEFORE the beat.

Guitarists can execute the trill with an upper prefix and termination (also called a descending trill, trill with turn from above, trill with double turn from above, and doppelt-cadence) with slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs), cross-string ornaments, or a combination of both. Example #33:

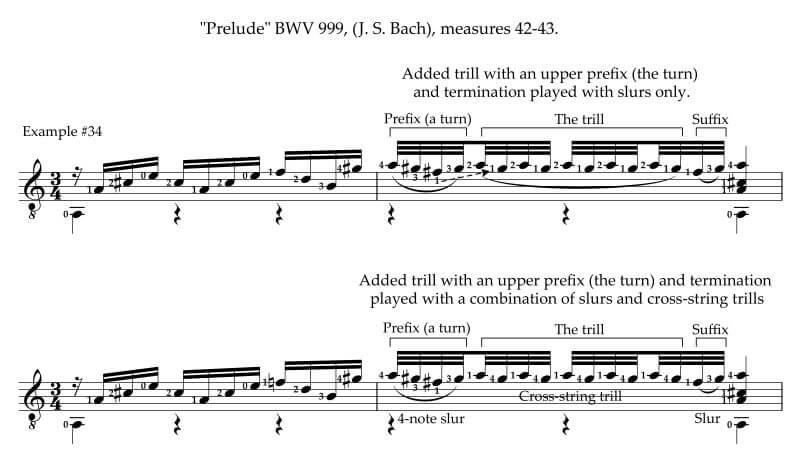

Here is an example of how to use the trill with an upper prefix (the turn) and termination in the "Prelude in D Minor" BWV 999 by J.S. Bach. Although the original manuscript didn't indicate a trill, adding ornaments at final cadences was a very common performance practice. To play the trill with an upper prefix (turn) and termination on the guitar, we can use all slurs or a combination of slurs with cross-string trills. Example #34:

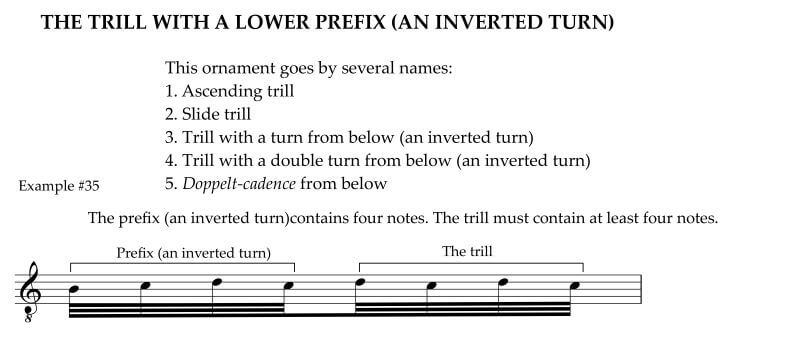

THE TRILL WITH A LOWER PREFIX (inverted turn)

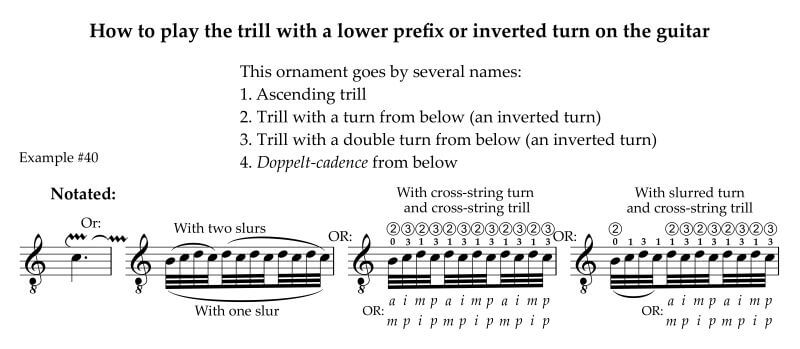

The trill with a lower prefix (inverted turn) goes by several names:

- Ascending trill

- Trill with a turn from below (an inverted turn)

- Trill with a double turn from below (an inverted turn)

- Doppelt-cadence (from below)

This trill with a lower prefix consists of a prefix and a trill. The prefix, which is an ornament called an inverted turn, consists of four notes: the auxiliary note below the principal note, the principal note, the auxiliary note above the principal note, and finally, the principal note. The prefix is followed immediately by a trill of at least four notes, beginning on the auxiliary note above the principal note. Example #35:

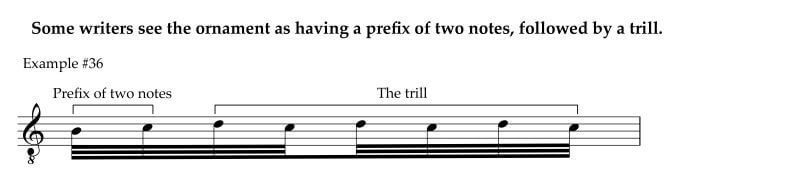

Some writers prefer to think of the prefix as only being two notes: the auxiliary note below the principal note and the principal note. Then, they think of the following notes as simply a trill starting on the auxiliary note above the principal note. Example #36:

However, in the table of ornaments Johann Sebastian Bach wrote out for his son, Wilhelm Friederich ("Explanation of various signs, intimating the way of gracefully rendering certain ornaments"), Johann calls the ornament a doppelt-cadence, a cadence being a turn. Therefore, it is clear he was thinking of the ornament as being an inverted turn followed by a trill.

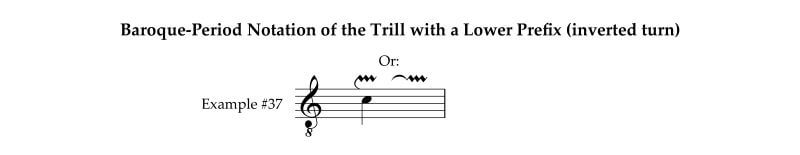

Notation of the trill with a lower prefix (inverted turn)

J.S. Bach notated this ornament as a letter C-like curve hanging down from the beginning of a long horizontal zig-zag line. Others notated it as a curved arched line connected to the left end of an equally long horizontal zig-zag line. Example #37:

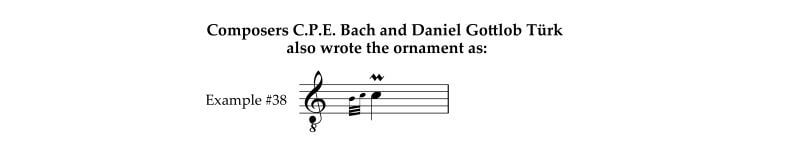

Composers C. P. E. Bach and Daniel Gottlob Türk also provided an alternative notation: two small grace notes, the first the auxiliary note below the principal note followed by the principal note itself (as a small grace note) and finally, the principal note in standard size with a zig-zag horizontal line above it. Example #38:

The number of note alternations in the trill with a lower prefix will vary. The length of the principal note is the primary determining factor since there is more time to play more notes in a longer note than a short one. The overall tempo of the passage will also be a factor. Here are examples of trills with a lower prefix using principal notes of different lengths and various ways to execute them. Example #39:

However, note that while the above examples show the trill with a lower prefix (an inverted turn) starting ON the beat, there are many examples in Baroque music of them starting BEFORE the beat.

Guitarists can execute the trill with the lower prefix (also called an ascending trill, trill with a turn from below (inverted turn), and doppelt-cadence from below) with slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs), cross-string ornaments, or a combination of both. Example #40:

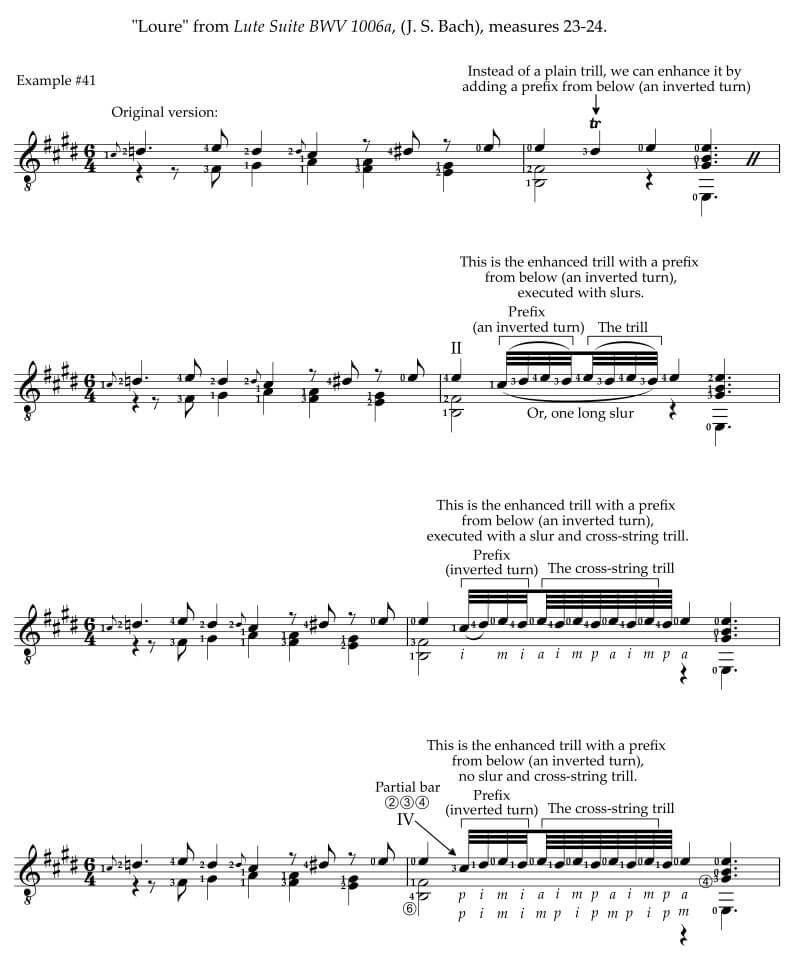

Here is an example of how to use the trill with a lower prefix (an inverted turn) in the "Loure" from Lute Suite BWV 1006a by J.S. Bach. Although the original manuscript only indicates a trill, enhancing ornaments at final cadences was a very common performance practice. To play the trill with a lower prefix (inverted turn) on the guitar, we can use all slurs or a combination of slurs with cross-string trills. Example #41:

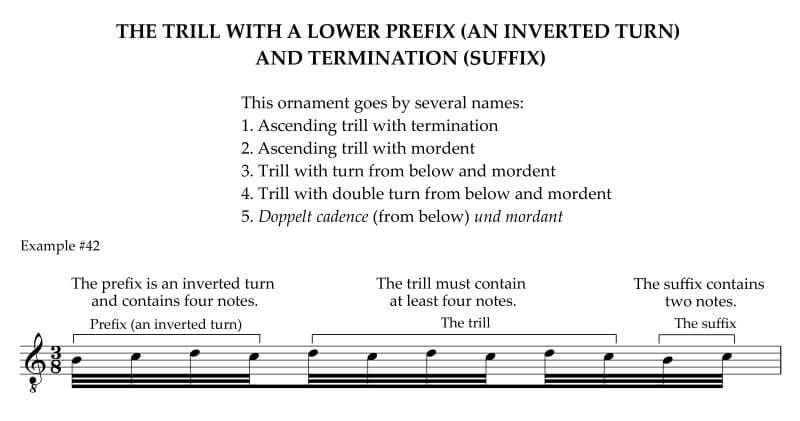

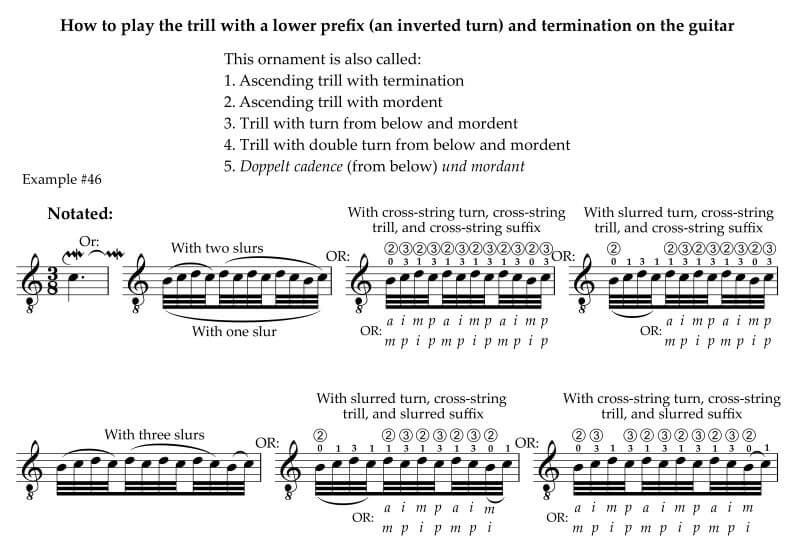

THE TRILL WITH A LOWER PREFIX (inverted turn) AND TERMINATION

The trill with a lower prefix (inverted turn) and termination goes by several names:

- Descending trill with termination

- Descending trill with mordent

- Trill with turn from below and mordent

- Trill with double turn from below and mordent

- Doppelt cadence (from below) und mordant

The inclusion of the word "mordent" in some of the names refers to the final three notes of the ornament forming a descending mordent.

The trill with a lower prefix and termination consists of three parts: the lower prefix, the trill, and a suffix or termination. The ornament starts with a prefix, which is an ornament called an inverted turn. It consists of four notes: the auxiliary note below the principal note, the principal note, the auxiliary note above the principal note, and finally, the principal note. The prefix or inverted turn is followed immediately by a trill of at least four notes, beginning on the auxiliary note above the principal note. The termination is a suffix. The suffix is the auxiliary note below the principal note and, finally, the principal note. Some writers call the suffix a nachschlag. Example #42:

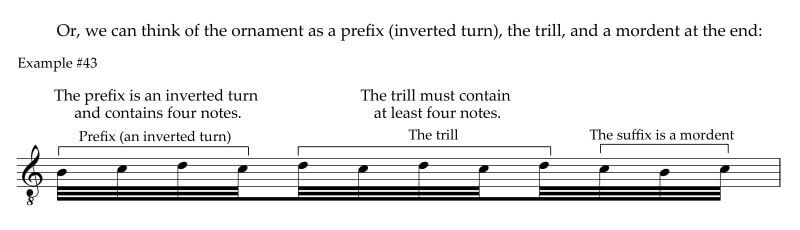

Or again, we can think of the ornament as starting with a lower prefix (turn), then the trill itself, and finally, a mordent as the suffix at the end. Example #43:

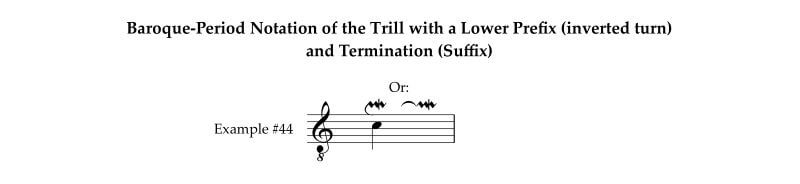

Notation of the trill with a lower prefix (inverted turn) and termination

J.S. Bach notated this ornament as a letter C-like curve hanging down from the left end of a long horizontal zig-zag line with a short vertical line passing through the zig-zag line right-of-center. Others notated it as a curved arched line connected to an equally long horizontal zig-zag line. Again, the horizontal zig-zag line has a short vertical line passing through it right-of-center to indicate a descending mordent at the end. Example #44:

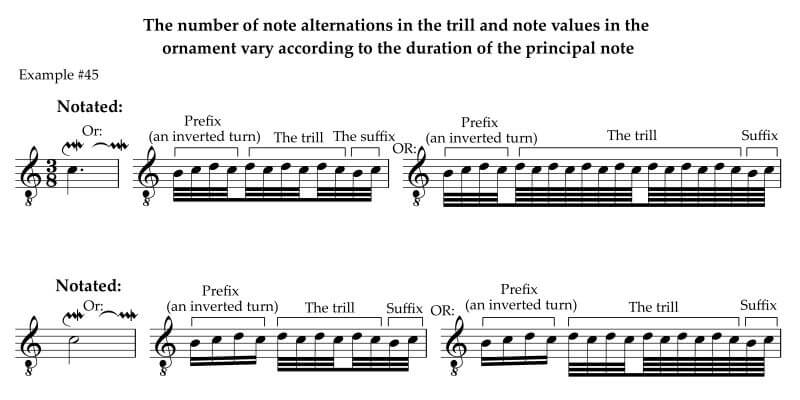

The number of note alternations in the trill with a lower prefix (inverted turn) and termination will vary. The length of the principal note is the primary determining factor since there is more time to play more notes in a longer note than a short one. The overall tempo of the passage will also be a factor. Here are examples of trills with a prefix using principal notes of different lengths and various ways to execute them. Example #45:

However, it is essential to note that while the above examples show the trill with a lower prefix (an inverted turn and termination) starting on the beat, there are many examples in Baroque music of them starting BEFORE the beat.

Guitarists can execute the trill with an upper prefix and termination (also called a descending trill, trill with turn from above, trill with double turn from above, and doppelt-cadence) with slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs), cross-string ornaments, or a combination of both. Example #46:

Here is an example of how to use the trill with a lower prefix (the inverted turn) and termination in the "Gavotte en Rondeau" from Lute Suite BWV 1006a by J.S. Bach. Although the original manuscript didn't indicate a trill, adding ornaments at final cadences was a very common performance practice. To play the trill with a lower prefix (inverted turn) and termination on the guitar, we can use all slurs or a combination of slurs with cross-string trills. Example #47:

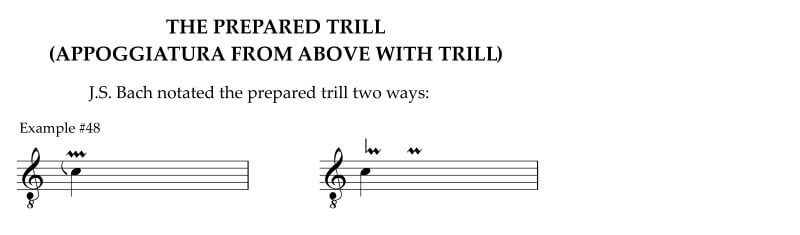

THE PREPARED TRILL (APPOGGIATURA FROM ABOVE WITH TRILL)

The prepared trill (appoggiatura from above the trill) goes by different names:

- Prepared trill

- Accent und trillo

- Appoggiatura from above with trill

Notation of the prepared trill

In the table of ornaments ("Explanation of various signs, intimating the way of gracefully rendering certain ornaments") that J.S. Bach wrote out for his son, Wilhelm Friederich Bach, Bach shows two ways to notate the ornament. One method placed a symbol resembling a left parenthesis to the left and slightly above the principal note with a zig-zag horizontal line above the principal note. The other used a relatively long vertical line at the start of a longer zig-zag horizontal line above the principal note. Example #48:

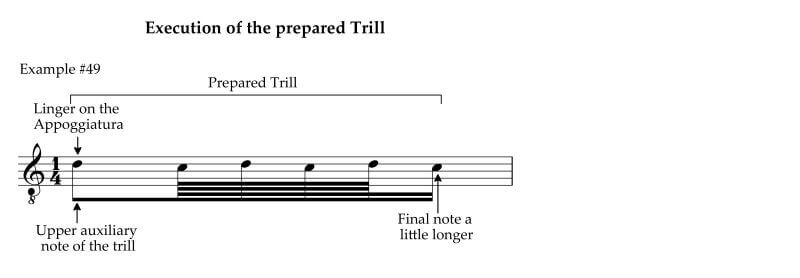

Execution of the prepared trill

In the Baroque period, musicians performed this trill by starting and lingering on the auxiliary note above the principal note of the trill. Lingering on the note made it sound like an appoggiatura. Then, they played the rest of the trill. The final note of the trill was a little longer than the preceding notes. Example #49:

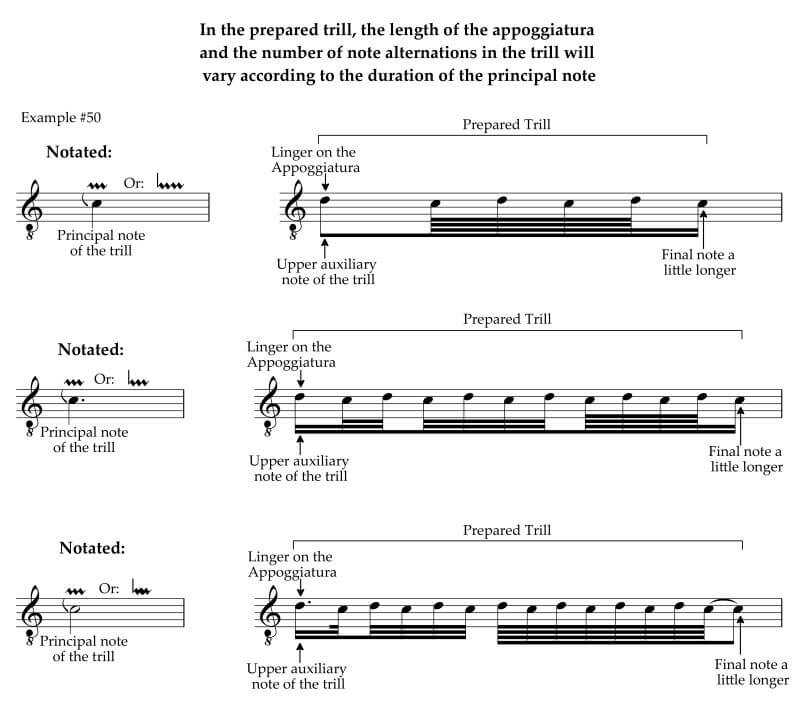

In the prepared trill, the length of the appoggiatura and the number of note alternations in the trill will vary. The length of the principal note is the primary determining factor since there is more time to hold the appoggiatura and play more notes in the trill in a longer note than a short one. The overall tempo of the passage will also be a factor. Here are examples of trills with a prefix using principal notes of different lengths and various ways to execute them. Example #50:

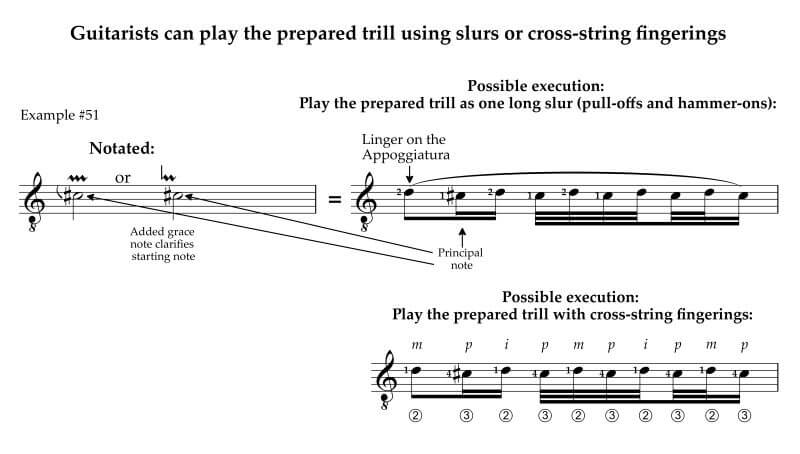

For guitarists, the execution of the prepared trill is the same as a regular trill. The guitarist can use slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs), cross-string fingering, or a combination of both. Example #51:

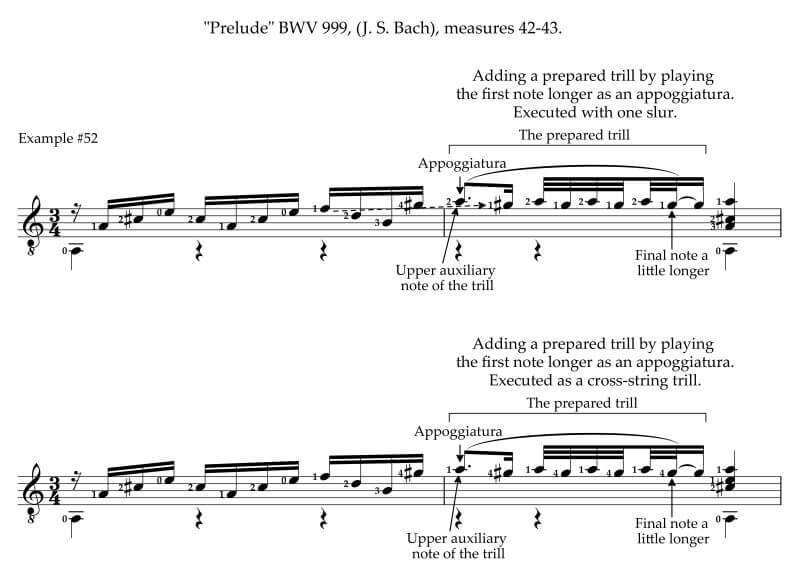

Here is an example of how to use the prepared trill (playing the first note as an appoggiatura) in the "Prelude in D Minor" BWV 999 by J.S. Bach. Although the original manuscript didn't indicate a trill, adding ornaments at final cadences was a very common performance practice. To play the prepared trill on the guitar, we can use all slurs or play it as a cross-string trill. Example #52:

THE MORDENT TRILL

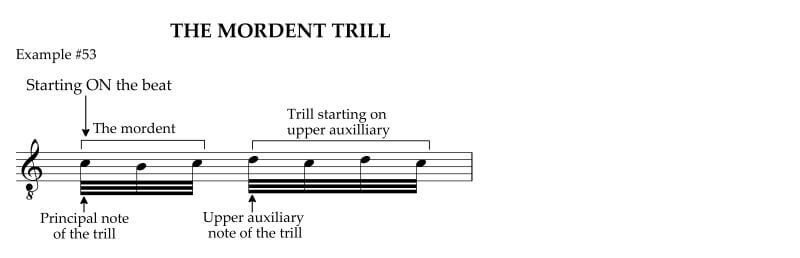

The mordent trill consists of three notes forming a descending mordent followed by a trill. Composers usually wrote the mordent trill in regular notation (not symbols). Like other trills, the question is whether it begins on the beat or anticipates the beat. Here it is, starting ON the beat. Example #53:

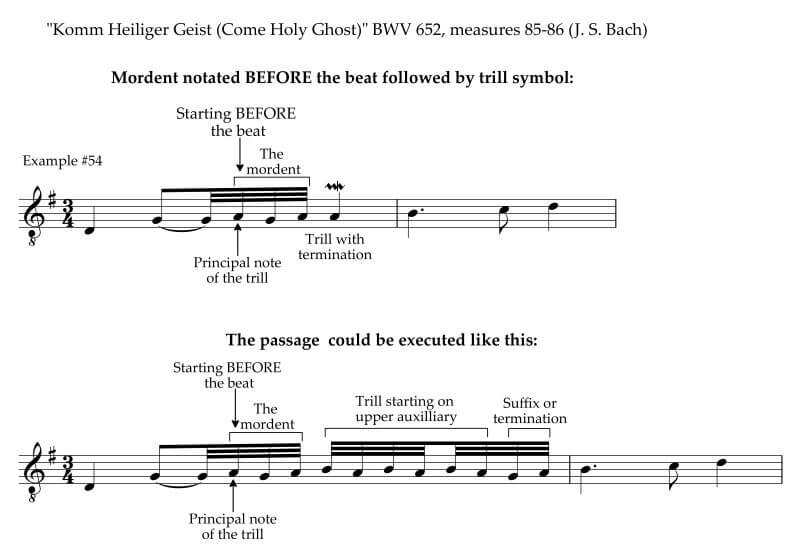

Here is a mordent trill as notated in J.S. Bach's "Komm Heiliger Geist (Come Holy Ghost)" BWV 652, measures 85-86. It clearly starts BEFORE the beat. Example #54:

THE SLIDE TRILL

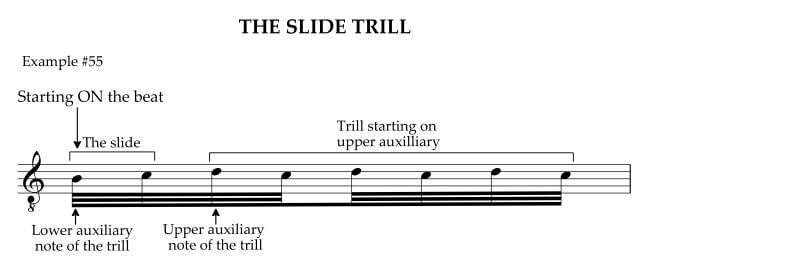

The most common slide trill consists of two notes before the trill (the lower auxiliary note and then the principal note) and then the trill itself beginning on the upper auxiliary note. Like other trills, the question is whether it begins on the beat or anticipates the beat. Here it is, starting ON the beat. Example #55:

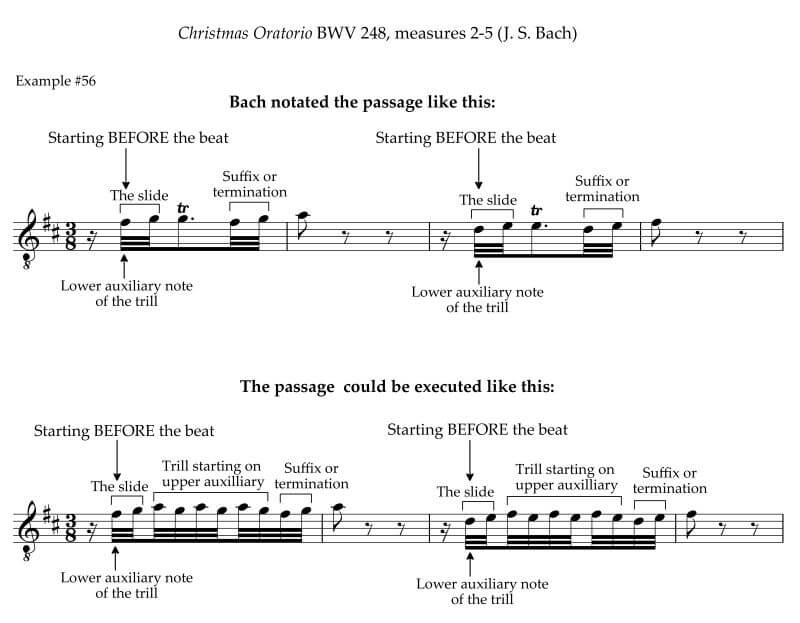

And here is a slide trill as notated in J.S. Bach's Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248, measures 2-4. It clearly starts BEFORE the beat. Example #56:

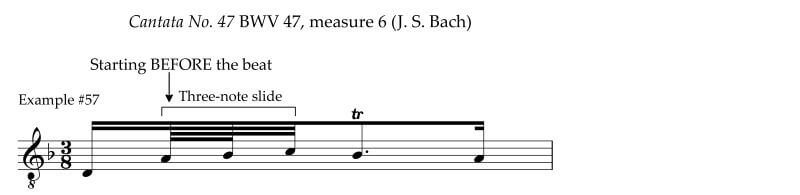

The slide of the slide trill can also contain three-note anticipations. Here is an example in measure 6 of the “Aria” from J. S. Bach's Cantata BWV 47. Again, note that the slide occurs BEFORE the beat. Example #57:

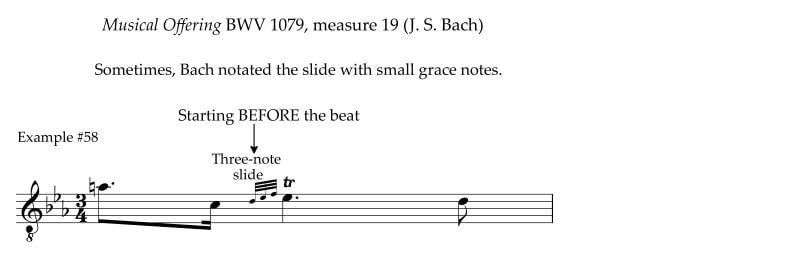

Sometimes, Bach notated a slide with grace notes as in his Musical Offering. Example #58:

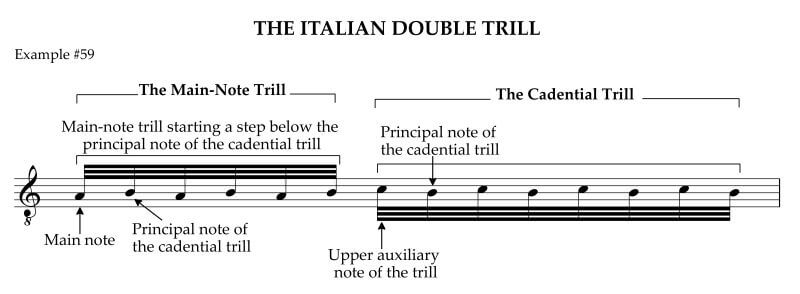

THE ITALIAN DOUBLE TRILL

The Italian double trill is relatively rare. Composer and violinist Giuseppe Tartini described it as a cadential trill (starting on the upper auxiliary note) preceded by a main-note trill a step below. Example #59:

Further Reading

If you want to explore any of these topics in-depth (630 pages), I highly recommend one of my favorite books, Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-Baroque Music With Special Emphasis on J.S. Bach by Frederick Neumann.

Cross-String Ornaments

Mordents (and many other ornaments) may be executed with slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs) or as cross-string ornaments. For detailed information on cross-string ornaments, see the following:

Cross-String Ornaments Part 1

Cross-String Ornaments Part 2

Cross-String Ornaments Part 3

DOWNLOAD THE PDF

Download the PDF here: ORNAMENTS: TRILLS