THE ORNAMENTAL ARPEGGIO:

Its notation, execution, and the challenges of historical interpretation

"Douglas who?"

Douglas Niedt is a successful concert and recording artist and highly respected master classical guitar teacher with 50 years of teaching experience. He is Associate Professor of Music (retired), at the Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City and a Fellow of the Henry W. Bloch School of Management—Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

Doug studied with such diverse masters as Andrés Segovia, Pepe Romero, Christopher Parkening, Narciso Yepes, Oscar Ghiglia, and Jorge Morel. Therefore, Doug provides solutions for you from a variety of perspectives and schools of thought.

He gives accurate, reliable advice that has been tested in performance on the concert stage that will work for you at home.

PURCHASE AN ALL-ACCESS PASS

TO THE VAULT OF CLASSICAL GUITAR TECHNIQUE TIPS

"Hello Mr Niedt,

My name's Gretchen, and I'm so happy I purchased an All-Access Pass to the Vault. I love your awesome technique tips. I'm amazed how much I have improved my playing.

Thank you!"

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR PROVEN STRATEGIES

THAT WILL MAKE YOU A BETTER GUITARIST?

Check out the game-changing tips in my Vault—I promise they will kick your playing up to the next level.

Purchase an All-Access Pass to the Vault.

It's a one-time purchase of only $36!

You receive full access to:

- Over 180 technique tips in The Vault.

- Special arrangements of Christmas music

- Arrangement of the beautiful Celtic song, Skellig

- Comprehensive guide, How to Master the Classical Guitar Tremolo

All that for a one-time payment of only $36. Take me to the page to Purchase an All-Access Pass

THE ORNAMENTAL ARPEGGIO:

Its notation, execution, and the challenges of historical interpretation

By Douglas Niedt

Copyright Douglas Niedt. All Rights Reserved.

This article may be reprinted, but please be considerate and give credit to Douglas Niedt.

PREFACE

The first thing you need to know when deciding how to play any ornament in pre-20th-century music is that there was no "common practice." The notation and execution of ornaments varied from country to country and composer to composer.

Written instructions from long ago or ornament tables (even by J.S. Bach) cannot overcome the general shortcomings of musical notation. Rigid rules, no matter where they come from, go against the very nature of ornaments—they were often improvised and, therefore, are too free to be tamed into regularity or taught by the book.

Descriptions of ornaments are only rough outlines, and many are contradictory. It's a jungle and very frustrating to try to figure out. There is simply no definitive solution to any ornament in a given situation. Therefore, be skeptical of everything I write from here on!

If you want a short answer to how to play an ornament, I say, "Do whatever you want. Do what makes the music sound best, and do what sounds best to you. In the end, that's what counts."

ARPEGGIOS AS ORNAMENTS

As guitarists, we are very familiar with strumming a chord with the right-hand thumb or with a combination of the right-hand thumb and fingers. However, especially in the Baroque period, theorists and composers thought of chord arpeggios as ornaments. Performers, especially keyboardists, frequently turned written block chords into elaborate arpeggios.

Composers frequently used ornamental arpeggios in harp and lute music in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Harpsichord and clavichord players soon appropriated these ornamental arpeggios into their music, turning them into complex configurations.

There are three main classes of ornamental arpeggios.

- The Plain or Simple (harpégé simple) Chordal Arpeggio

- The Figurate Chordal Arpeggio (arpégé or harpégé figuré)

- The Linear Arpeggio

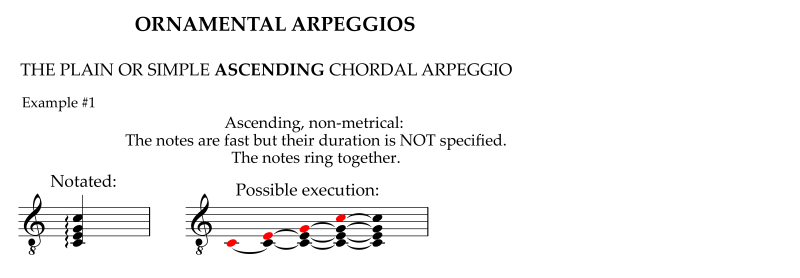

The Plain or Simple (harpégé simple) Chordal Arpeggio:

This arpeggio uses only the pitches of the chord. The performer plays the pitches in very close succession without any specified rhythm. The pitches sustain to form the harmony of the complete chord. The Plain or Simple Chordal Arpeggio is the class of arpeggios that guitarists use when strumming a basic folk-guitar-style chord. The most common configuration is for the performer to "break" the chord with an ascending arpeggio (low pitches to high pitches).

For guitarists, a down strum (strumming toward the floor) with the right-hand thumb creates an ascending arpeggio. This happens because the strum starts from the 6th string, the lowest pitch, and moves to the 1st string, the highest pitch, playing each subsequent string in order of increasing pitch. Example #1:

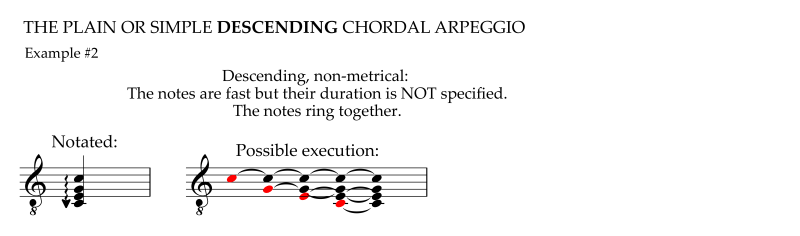

Or, the performer can "break" the chord with a descending arpeggio (high pitches to low pitches). For guitarists, an up strum (strumming up towards the ceiling) with the right-hand thumb or a right-hand finger creates a descending arpeggio. This happens because the strum starts from the 1st string, the highest pitch, and moves to the 6th string, the lowest pitch, playing each subsequent string in order of descending pitch. Example #2:

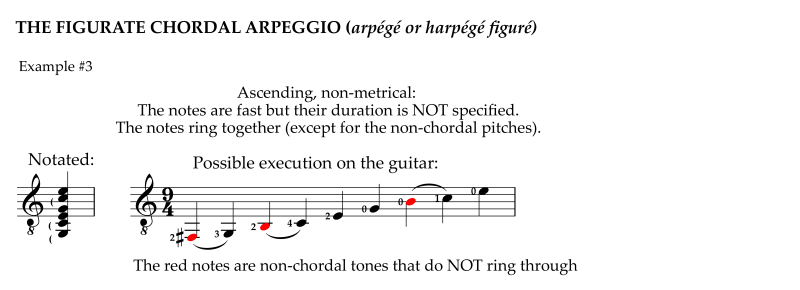

The Figurate Chordal Arpeggio (arpégé or harpégé figuré):

In this arpeggio, the performer inserts non-chordal tones (that he does not sustain) within the chord. The non-chordal tones are usually a half step away from a chordal tone. Example #3:

Figurate Chordal Arpeggios could be elaborate in Baroque music, especially at a fermata. The performer would make the arpeggio ascend and descend, perhaps several times, adding non-chordal notes as he pleased.

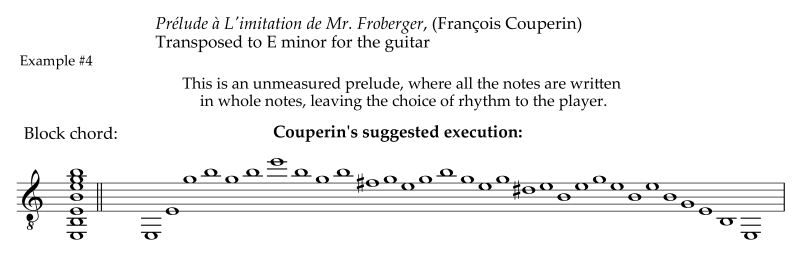

In his Prélude à L'imitation de Mr. Froberger, François Couperin gives an example of a block chord and shows one way to arpeggiate it. We notice a more or less immediate ascent through the chord's notes from bottom to top, followed by a gradual descent featuring upward and downward meanderings. He inserts two non-chordal tones (the B and the G#) in the arpeggiation for spice. The piece is an unmeasured prelude, where all the notes are written in whole notes, leaving the choice of rhythm to the player. Example #4:

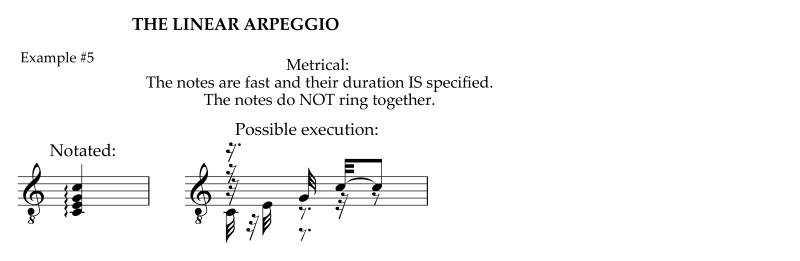

The Linear Arpeggio:

The performer plays the arpeggio as a string of individual pitches in a defined rhythm. The pitches sound one at a time and do not sustain. Example #5:

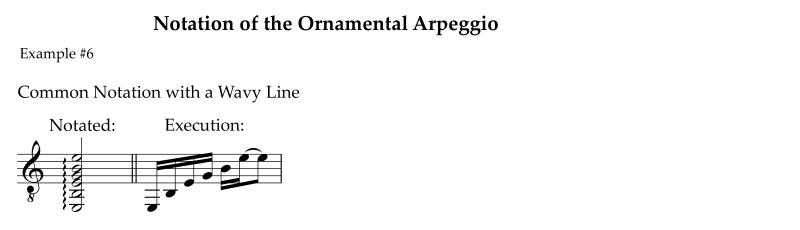

Notation and Execution of the Plain or Simple Arpeggio as an Ornament

As with most ornaments, composers used several symbols to notate the arpeggio ornament in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The most common, which survives today, is the vertical wavy line placed to the left of the chord. Example #6:

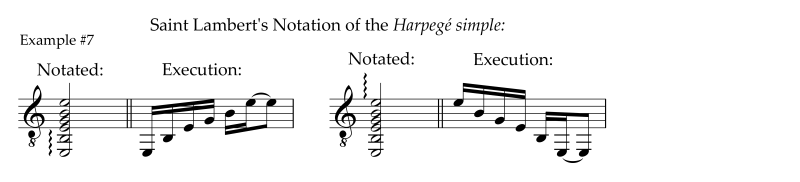

Theorists such as Saint Lambert placed the wavy line toward the bottom of the chord to indicate an upward arpeggio or toward the top to indicate a downward arpeggio. Example #7:

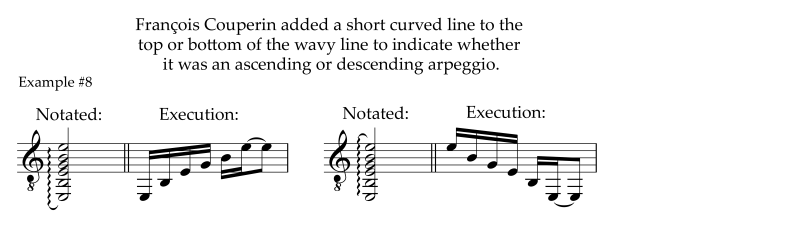

French composer, organist, and harpsichordist François Couperin added a short curved line to the top or bottom of the wavy line to indicate whether it was an ascending or descending arpeggio. Example #8:

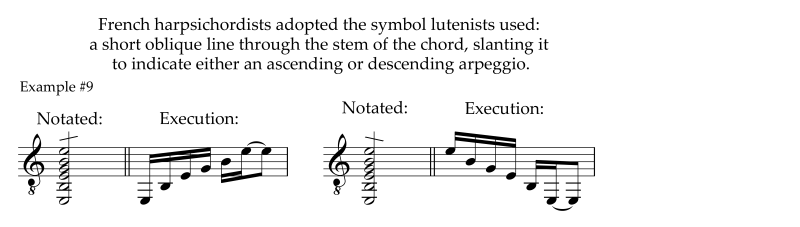

In addition to variations of the wavy vertical line, French harpsichordists also adopted the symbol lutenists used: a short oblique line through the stem of the chord, slanting it to indicate either an ascending or descending arpeggio. Example #9:

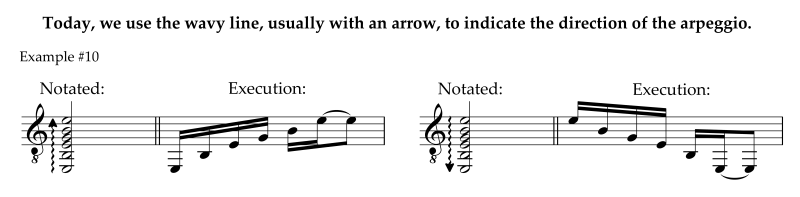

Today, we use the wavy line, usually with an arrow, to indicate the direction of the arpeggio. Example #10:

Do We Play the Plain or Simple Arpeggio ON the beat or BEFORE the Beat?

As with so many other ornaments, we have the choice of whether to play the plain or simple arpeggio on the beat or before the beat.

Starting a Chordal Arpeggio BEFORE the beat (anticipatory)

The context of the passage determines whether we play the Plain or Simple Arpeggio on the beat or before the beat (anticipatory). In a passage with fast notes before the arpeggio, there is no time to start the arpeggio before the beat.

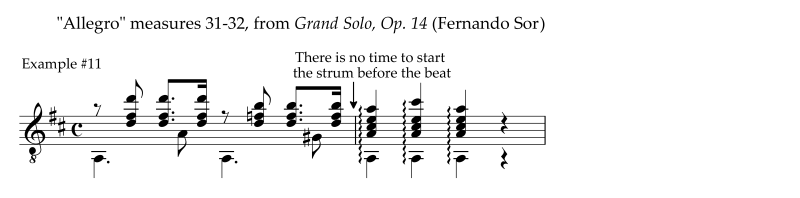

In measures 31-32 of the "Allegro" from Grand Solo, Op. 14 by Fernando Sor, we cannot start the arpeggio before the beat because the piece is fast, and the note before the arpeggio is a 16th note. There is simply no time to start the arpeggio before the beat. Example #11:

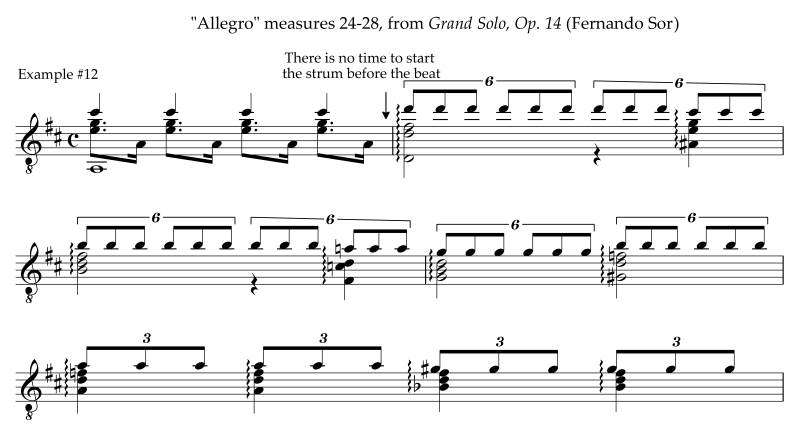

However, in measures 24-28, from Grand Solo, Op. 14 by Fernando Sor, once again, there is no time to start the first arpeggio before the beat because the last note of the previous measure is a 16th note. Example #12:

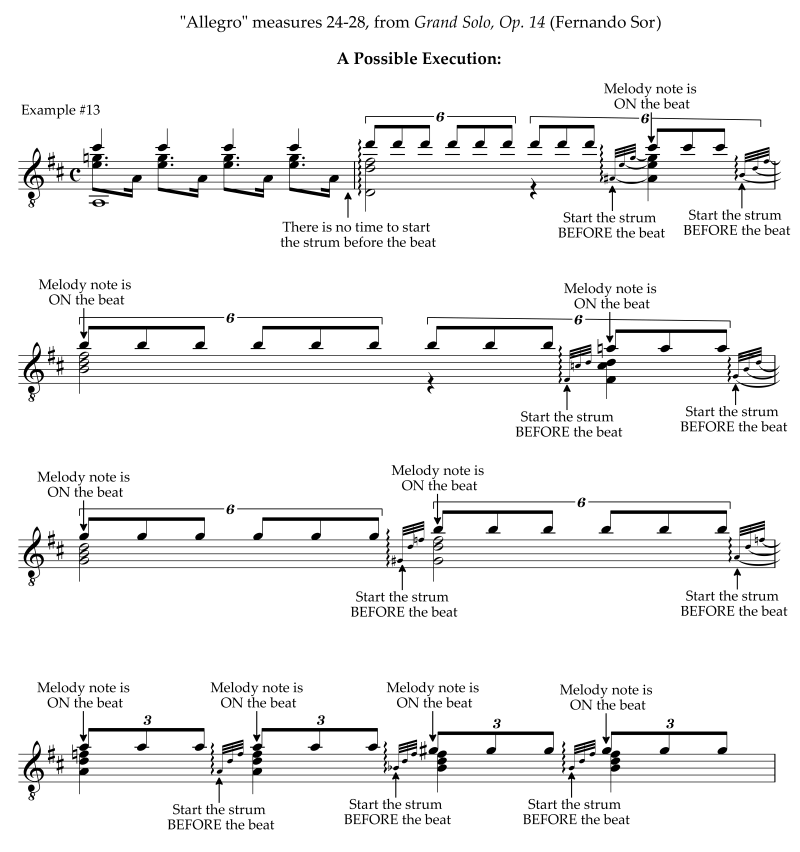

We do have time to start most of the rest of the arpeggios before the beat. Starting the arpeggios before the beat has an important benefit here and in many other pieces. If we start the arpeggio BEFORE the beat, the melody, which is the top note of the arpeggio, stays ON the beat, where it should be. Example #13:

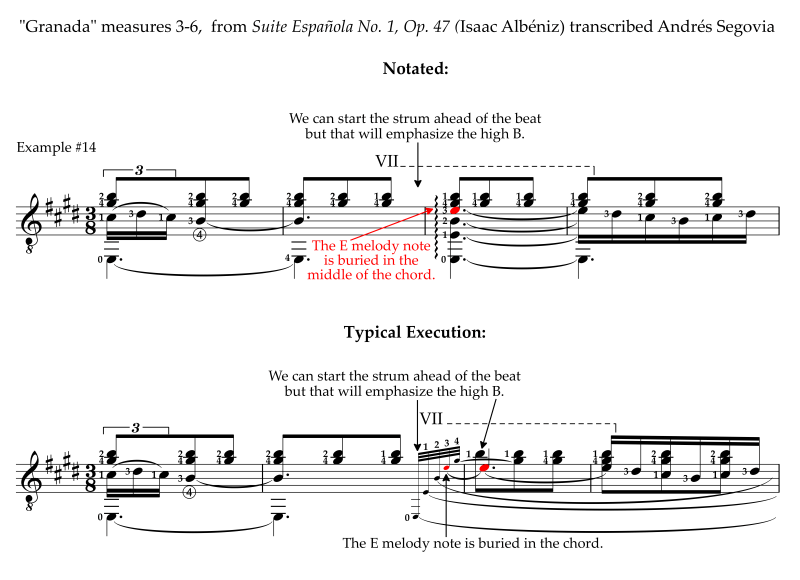

Measures 1 and 5 of Andrés Segovia's transcription of "Granada" from Suite Española No. 1, Op. 47 by Isaac Albéniz begin with a strummed chord marked with a wavy line. However, the melody note is buried in the middle of the chord, so the execution is trickier than a typical strum. We can start the strum before the beat, but that will emphasize the high B on the 1st string. We want to emphasize the melody, which is the 3rd-string E. Example #14:

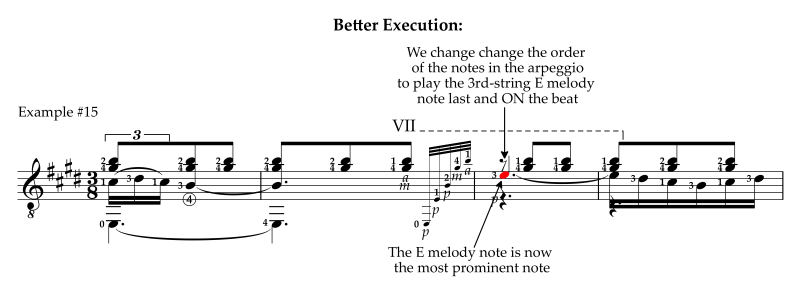

But if we change the order of the notes within the arpeggio, we can play the 3rd-string E melody note last, placing it ON the beat where it receives its needed emphasis. Example 15:

Starting a Chordal Arpeggio ON the beat

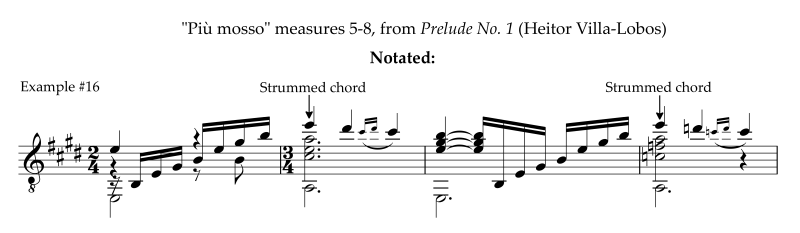

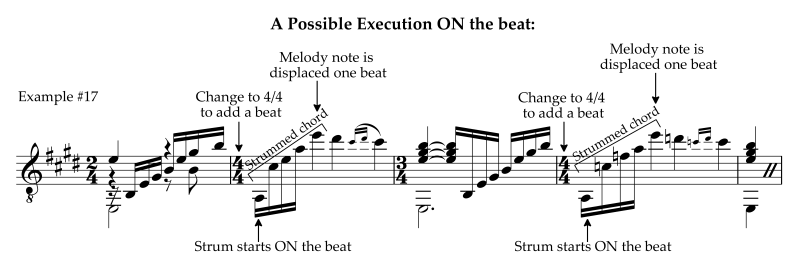

Sometimes, it is best to start the arpeggio ON the beat and intentionally play it rather slowly instead of anticipating it. For instance, we have strummed chords in measures 5-8 of the "Più mosso" section of Prelude No. 1 by Heitor Villa-Lobos. Example #16:

Although Villa-Lobos did not explicitly notate the chords with the wavy arpeggio symbol, most guitarists strum both. Because of the fast tempo, we can't start either arpeggio before the beat to place the high melody note on the downbeat. Therefore, the solution for these chords, and many others like them in other pieces, is to play the lowest note of the chord ON the beat and purposely strum at a moderate speed, delaying the sounding of the high melody note. The delay draws the listener in and emphasizes the melody note. Example #17:

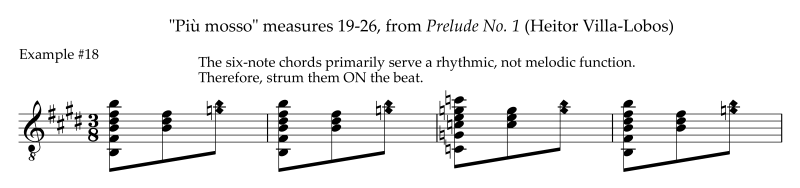

In measures 19-26 of the same piece, we have a series of strummed chords. In this case, their function is rhythmic rather than melodic; therefore, ON-the-beat execution suits the passage best. Example #18:

THERE ARE TWO RULES TO HELP YOU DECIDE WHETHER TO START A CHORDAL ARPEGGIO ORNAMENT BEFORE THE BEAT (ANTICIPATORY) OR ON THE BEAT

- RULE #1: Rule #1 of executing ornamental CHORDAL ARPEGGIOS is that if the melody of the chord is the top note, try to start the arpeggio BEFORE the beat so that the melody note falls ON the beat where it belongs.

- RULE #2: Rule #2 is that if the function of the chord arpeggio is rhythmic rather than melodic, it is usually best to start the arpeggio ON the beat. The performer can also use ON-the-beat execution to intentionally delay the melody note to give it extra attention and emphasis.

Notation and Execution of the Figurate Arpeggio

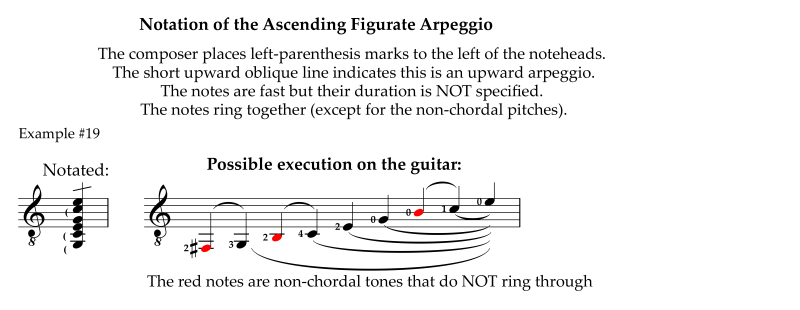

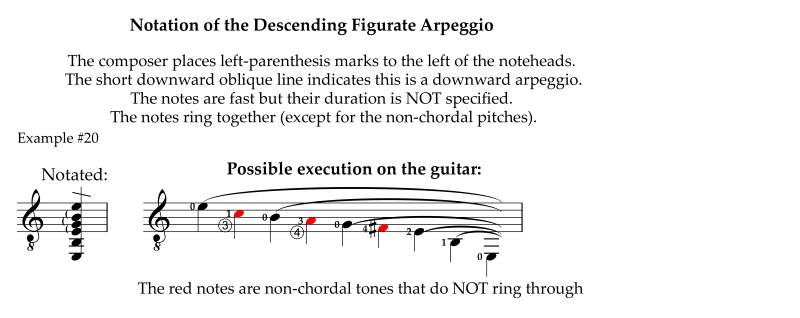

In the Figurate Chordal Arpeggio (arpégé or harpégé figuré)the performer inserts non-chordal tones (that he does not sustain) within the chord. The non-chordal tones are usually half a step away from a chordal tone. They are usually ascending and NON-metrical. The notes are fast, but their duration is NOT specified. The notes ring together (except for the non-chordal pitches).

Composers sometimes notated the Figurate Arpeggio with left-parenthesis marks to the left of the noteheads (sometimes with a short upward or downward oblique line to indicate the direction of the arpeggio). Example #19:

Or, composers would place an oblique line through the note stem. If the oblique line slanted upward, it was an ascending Figurate Arpeggio. If the oblique line slanted downward, it was a descending Figurate Arpeggio. Example #20:

Notation and Execution of the Linear Arpeggio

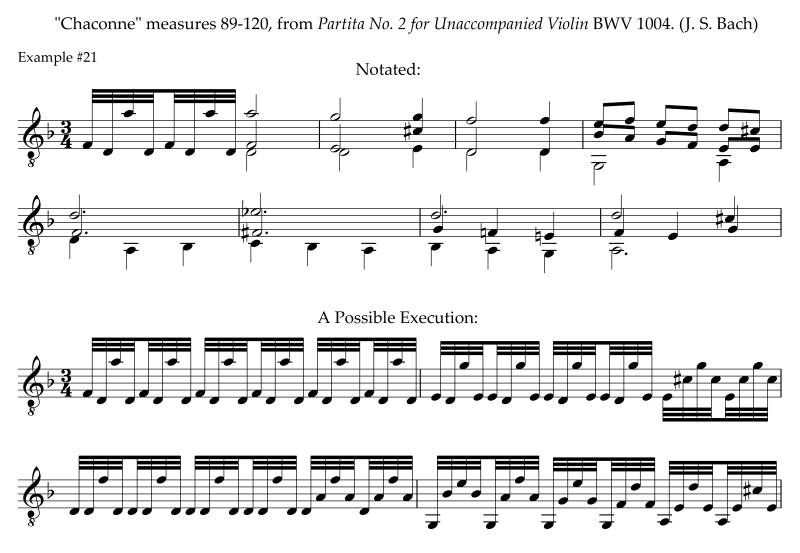

The performer plays the arpeggio as a string of individual pitches in a defined rhythm. The pitches sound one at a time and do not sustain. These arpeggios are most recognizable in solo violin and cello music.

One of the most famous examples appears in measures 89-120 of the famous "Chaconne" from Partita No. 2 for Unaccompanied Violin BWV 1004 by J. S. Bach. Bach notates the first beat of measure 89 as an arpeggio but then leaves it to the performer to use his skill and intuition to decide how to play all the chords that follow as arpeggios. Of course, since the violin is playing the passage, none of the notes can ring over into the following notes, so the result is a linear arpeggio. Example #21:

Further Reading

If you want to explore any of these topics in-depth (630 pages), I highly recommend one of my favorite books, Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-Baroque Music With Special Emphasis on J.S. Bach by Frederick Neumann.

DOWNLOAD THE PDF

Download the PDF here: ORNAMENTS: ARPEGGIOS