Douglas Niedt Presents

PLAY IT LIKE A PRO™

Learn to play "Sounds of the Bells"

(Sons de Carrilhões) with

Professional-Level Execution.

Play It Like a Pro!

For intermediate and advanced guitarists.

This Play It Like a Pro™ Package is the most comprehensive tutorial for “Sounds of the Bells” on the planet. Nothing else comes close.

If you are unfamiliar with the piece, watch Stephanie Jones' delightful rendition of the conventional or common version of "Sounds of the Bells."

"Sounds of the Bells" (conventional version)

performed by guitarist Stephanie Jones

Altering the rhythm patterns, melodies, bass lines, harmonizations, and other elements of repeated measures or sections is an essential part of authentically performing Brazilian choro music. (More on this below.) Watch Doug perform this type of "tricked-out" version.

"Sounds of the Bells" (Doug's tricked-out version)

performed by guitarist Douglas Niedt

THIS IS WHAT YOU GET IN THE PLAY IT LIKE A PRO™ "SOUNDS OF THE BELLS" PACKAGE

THIS PACKAGE CONSISTS OF FOUR BOOKS OF INSTRUCTION:

BOOK 1: Fingering, Technique, and Groove (172 pages, 68 videos)

This book takes you through the piece measure by measure showing different published versions of each measure, dozens of alternate fingerings, technical advice on how to execute each measure successfully, and instructions on using accents, articulations, and slurs to add "ginga" (groove) to your performance.

To navigate, click on the arrows in the music example

or use the right/left arrows on your keyboard.

To close, click anywhere outside the image or the X below the music.

BOOK 2: "Tricking Out" Your Interpretation (72 pages, 24 videos)

Altering the rhythm patterns, melodies, bass lines, harmonizations, and other elements of repeated measures or sections is an essential part of authentically performing Brazilian choro music. This book shows dozens of alternative versions of the music. These examples are to provide guidance and inspire you to create your own ideas. This will give your performance a "vibe" of spontaneity and give your interpretation an improvisatory flair. These examples stay close to the rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic language of the time. I chose not to include modern jazz harmonizations or improvisations.

To navigate, click on the arrows in the music example

or use the right/left arrows on your keyboard.

To close, click anywhere outside the image or the X below the music.

BOOK 3: Form & Analysis (the structure of the piece)

This book provides a three-page summary of the form of the piece and a color-coded score that details its structure

To navigate, click on the arrows in the music example

or use the right/left arrows on your keyboard.

To close, click anywhere outside the image or the X below the music.

BOOK 4: The Interpretation Score (6 pages)

This Book provides brief notes on tempo, rubato, vibrato, and detailed schemes of dynamics and tone color changes you can use to create your own interpretation.

Click the image below to view sample pages.

To navigate, click on the arrows in the music example

or use the right/left arrows on your keyboard.

To close, click anywhere outside the image or the X below the music.

THE PACKAGE ALSO INCLUDES SEVEN SCORES (PDFs):

- The conventional, common version in standard notation. Notated in three voices (see below).

- The same in standard notation plus TAB.

- The same in TAB only.

- Doug’s “Tricked-Out” version in standard notation.

- The same in standard notation plus TAB.

- The same in TAB only.

- A “blank” score with the notes only, so you can write in your own fingerings.

To navigate, click on the arrows in the music example

or use the right/left arrows on your keyboard.

To close, click anywhere outside the image or the X below the music.

Note that there is no tutorial on how to play “Doug’s Tricked-Out Version.” You are certainly welcome to play my version as is, but I encourage you to work with Book 2 of the tutorials to compose your own “tricked-out” version! It’s fun and gives you a chance to exercise your creative muscles.

The package also includes the PDF, "THIS IS EVERYTHING YOU SHOULD KNOW BEFORE YOU BEGIN LEARNING THE PIECE" which includes the story behind the piece, why it is titled "Sounds of the Bells," why there are two versions of the piece, a detailed explanation of the rhythms the piece is based on (maxixe and choro), how to play it with authentic style, biographical information about Pernambuco, and much more.

PLUS, THE PACKAGE CONTAINS 92 INSTRUCTIONAL VIDEOS!

Doug's 92 detailed instructional videos contain SIX HOURS of instructional video and will help you play "Sounds of the Bells" like a pro. Doug demonstrates how to play the piece measure by measure.

These are not "put your finger here and then put your finger there" type videos. Doug explains all the technical and musical details required to play the piece on a professional level.

Watch this video of measures 30-33 where he explains how to execute some of the most challenging chord changes in the piece.

Sample Instructional Video #66 for "Sounds of the Bells," measures 30-33

Watch it in high definition on full screen:

- Click the Play Button.

- In the lower right, click the gear icon, click "Quality," and in the dropdown list, choose 1080p (best) or 720p.

- For fullscreen, (go ahead, make it spectacular!) click the rectangle on the lower right.

ORDER NOW

This is a digital download.

The entire Play It Like a Pro™: "Sounds of the Bells" package (253 pages, 7 scores, 92 instructional videos) is only $39.95. It includes all four books of instruction, seven scores, and 92 videos.

Credit Card or PayPal.

Please click to go to the STORE to

add this item to your shopping cart

THIS IS EVERYTHING YOU SHOULD KNOW

BEFORE YOU BEGIN LEARNING THE PIECE.

Why Notate The Music In 3 Voices?

Note that most printed editions, old or new, notate the music in two voices using “shorthand” guitar notation. However, in my version, I notate the music more precisely in three voices or parts. The sound will be the same, but reading the music in three voices will help the performer see the independence of the voices and understand the subtleties of balance, articulation, and string damping that will bring clarity to the piece as a whole.

PRONUNCIATION GUIDE

Sons de Carrilhões: ||sōhns||day||kah-reel-ōh-ace||

João: In Portuguese, João is pronounced: J-ew-ow (slight slur in the J sounds like a short “shoo-ow.”

Pernambuco (pair-nahm-boo-kōh)

João Teixeira Guimarães (Pernambuco’s real name): ||shoo-ow||tay-shayee-rah||ghee-mar-rah-eesh||

Maxixe: (mah-shee-shee or mah-sheesh-shah). Listen to these two pronunciations of maxixe.

Choro: (shō-rōh)

Cavaquinho: (kah-vah-keen-yōh)

Pandeiro: (pahn-dayee-rōh)

THE STORY BEHIND "SONS DE CARRILHÕES,"

THE MOST POPULAR GUITAR PIECE IN BRAZIL

João Teixeira Guimarães or João Pernambuco?

"Sons de Carrilhões" ("Sounds of Bells") or "Sounds of the Bells," as I prefer to anglicize it, is one of the most popular guitar pieces in Brazil. The composer of "Sounds of the Bells," João Teixeira Guimarães, was born on November 2, 1883, in the hinterland of Bebedouro de Jatobá in the Brazilian state of Pernambuco, where he lived until 1895.

João learned to play his first chords on the guitar at the age of eight, taught by guitarist Laurindo Punga. As a youth, João worked as a helper in an oxcart workshop.

In 1895 João began his itinerant journey from the Sertão (the semi-arid region of northeastern Brazil) to the coast, going to Recife (the capital of the state of Pernambuco), where he continued to learn the guitar with Cirino da Guajurema, and Mané do Riachão in the surroundings of fairs and markets. In Recife, he became a blacksmith by profession and a guitarist by vocation.

He moved to Rio de Janeiro in 1904. João often told his friends and fellow musicians stories about his early life in Pernambuco and performed his musical compositions, which had solid Pernambucan roots. His friends began calling him Pernambuco, so he dropped Teixeira Guimarães and became known to all as João Pernambuco.

Why "Sounds of the Bells?"

Oxcarts, carts with wooden wheels, were Brazil’s primary mode of transportation during the late 1800s and early 1900s. Oxcarts transported people and goods throughout the country. As a boy, Pernambuco worked in an oxcart workshop and later as a blacksmith, so he would have worked both on oxcarts and making shoes for oxen.

Some oxcarts were decorated with custom artwork and designed to make their own "music." A metal ring striking the hub nut of the wheel produced a unique chime as the cart bumped along. Pernambuco wrote "Sounds of the Bells" in 1912, inspired by the sounds of these oxcart chimes, which João heard so often in his childhood in the backlands of Jatobá.

Why are there two versions of "Sounds of the Bells?"

"Sounds of the Bells" consists of rhythmic patterns from a Brazilian dance called the maxixe. You may have come across two versions of "Sounds of the Bells" with two very different rhythmic structures.

Version No. 1 is "square" like this:

Printed editions that use this “square” pattern look like this:

Version No. 2 has a syncopated rhythm with more of a “swing”:

Printed editions that use the syncopated “swing” pattern look like this:

To understand why there are two versions, we need to learn about the background of the maxixe and its rhythms. Also, let me be clear. Contrary to the opinion of some writers that the “swing” version is wrong, neither version is more accurate or authentic than the other. Which one you choose to play is a matter of personal choice. Pernambuco (playing the guitar) and Nelson Alves (playing the cavaquinho) mix the two rhythms in their 1926 recording of “Sounds of the Bells.” More on that later.

"Sounds of the Bells" with mixed rhythms.

I recommend combining both versions, which, as you will see, might be a little more authentic than strictly playing one version. For example, in an ensemble, one musician may play the “square” rhythm, but other musicians almost always overlay the “swing” rhythm on top of it. The key is that native players do not follow formulas. Instead, they change things, create variations, improvise, and mix elements to form a unique voice or interpretation. With the information in this instructional package, you can do the same!

The Maxixe

Some historians define the maxixe as the first authentically Brazilian genre. Its origins are related to a couple’s dance. It was sensual and extravagant, becoming popular in Rio de Janeiro’s ballrooms by the end of the nineteenth century. At first, arbiters of taste banned the maxixe from the more traditional segments of society due to its lustful characteristics. But eventually, it was accepted at all levels and became a national fever, replacing the polka.

Watch Oskar and Anna Tropp dance the Maxixe (1915).

The maxixe was a union between the polka and lundu, combined with elements from the African batuque and the habanera. Little by little, the maxixe became a unique musical genre.

One of the most significant contributors to the establishment of the genre was composer and pianist Ernesto Nazareth. The rhythmic elements of the maxixe infused his extensive body of works for piano solo, principally in the accompaniment played by the left hand.

Military bands, civil bands, carnival bands, and community musical associations frequently performed the maxixe. These groups consisted of wind and percussion instruments.

The maxixe had a fundamental role in the birth of the samba. Indeed, the first samba ever recorded, “Pelo Telefone,” written by Ernesto Maria dos Santos (a.k.a. Donga) in 1916, sounds like a maxixe rather than the samba we know today.

“Pelo Telephone” was a response to a law prohibiting gambling. But not only gambling was pursued by the police. Music could also be a danger to society. On September 25, 1918, police chief Aurelino Leal issued “Provisions for the Festa da Penha.” He wrote, “I also recommend that you absolutely do not allow the entertainment called ‘Samba,’ since such entertainment has been the cause of discord and conflicts.”

The Primary Rhythmic Structure

“Sounds of the Bells” is in a maxixe rhythm. The bass line and accompaniment establish the primary rhythmic structure of the maxixe.

But the maxixe can consist of several different rhythmic cells or patterns. The bass and accompaniment patterns can be one or more of these:

Watch the Band of Military Police of the Brazilian State of São Paulo

perform a maxixe.

If you focus on one pattern at a time and tap or clap along, you will hear cells 1-3 in the clip. Different groups of instruments play various cells at the same time.

If we look again at “Sounds of the Bells,” the “square” version uses cell or pattern #1. But the syncopated “swing” version uses cell or pattern #3. Guitarists Dilermando Reis and Pernambuco used the “square” rhythm in their published versions of the piece. Guitarist and authority on Brazilian music, Turibio Santos uses the “swing version in his published version. However, Pernambuco (playing the guitar) and Nelson Alves (playing the cavaquinho) mix the two rhythms in their 1926 recording of “Sounds of the Bells.”

"Sounds of the Bells" with mixed rhythms.

The “Play It Like a Pro™” package uses the “swing” version as its basis. But you can use the “square” pattern as the basis for your version if ou prefer. The fingerings and performance instructions will be the same.

Unlike an ensemble or military band, the guitar restricts us to playing either the “square” or “swing” rhythm pattern at a time within a measure. Note that I specify within a measure. No rules say you can’t use more than one pattern in the piece by applying different patterns to different measures. The maxixe is a fun and playful dance. It is okay to change things up as you wish. The groove, what Brazilian musicians call the “levada,” of the maxixe is free. You can “compose” the levada that you want.

The Secondary Rhythmic Structure

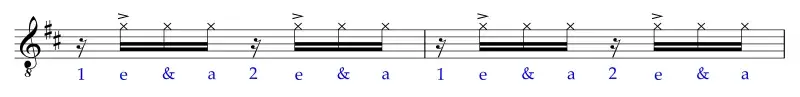

The snare drum and the accentuations of the pandeiro and the cavaquinho establish the secondary rhythmic component of the maxixe.

The maxixe patterns for the snare drum, pandeiro, and cavaquinho can consist of several different rhythmic cells or patterns. The patterns can be one or more of these:

We can apply Pattern #1 to the melody of “Sounds of the Bells” in much of Part 1 and for some measures in Part 2:

Here we apply the pattern to measures 1-12:

Measures 13-14, 22-23, and m30 can use Pattern #2 (without the trill):

Here it is in measures 13-14:

And, of course, Pattern #3 (without the trill) is the basis of the accompaniment in the “swing” version:

But we can also apply it to the melody of the “swing” version in measures 18-21, 24-29, and 33 of Part 2. Here it is in measures 18-19:

I explain how you can apply these maxixe rhythm patterns to “Sounds of the Bells” in Book 1: “Fingering, Technique, and Groove” and Book 2: “Tricking Out Your Interpretation.”

Choro

Various printed editions of “Sounds of the Bells” show a strong connection with the choro. One edition titles the piece “Choros.” Another edition titles the piece “Sons de Carilhões” (Carrilhões misspelled with one r) with “Maxixe-Chôro” as the subtitle. A version published in the Revista Musical has “Choro para Violão” in parenthesis under the title and “MAXIXE” as a subtitle. By the way, violão is Portuguese for guitar. Yet another edition only shows “Maxixe” as the subtitle.

The choro is both a genre and a rhythm pattern. Choro is one of the bedrock styles of Brazilian music. The term “choro” initially referred to a piece bursting with lyricism, creativity, and virtuosity. Middle-class musicians from Rio de Janeiro freely appropriated the European dances brought to the Portuguese Brazilian court: polkas, mazurkas, waltzes, schottishes, and others. These dances were “spiced up” with the strong influence of African rhythms.

The typical choro ensembles called Regionais feature melodic instruments for the soloist part, such as flute, mandolin, and clarinet. The cavaquinho plays harmony and rhythm, the pandeiro is the primary percussion instrument, and six and seven-string guitars are responsible for the harmony and the countermelodies in the bass. These countermelodies, called “baixarias,” are strongly characteristic of choro.

The word choro also designates a specific rhythm within its own repertoire, one that could be either fast, moderate, or slow (slow choros are called “choro-canção”). Choros have this basic outline:

We can see that the syncopated “swing” version of “Sounds of the Bells” contains some of the elements of the basic choro rhythm:

REMEMBER: The choro and maxixe share some of the same rhythmic cells or patterns. Hence, the subtitle in some editions of “maxixe-choro. This next version mixes characteristic rhythm patterns of both dances. This version applies the syncopation and bass rhythm of a basic choro rhythm to the first half of each measure. But it emphasizes the typical 8th-8th rhythm of the maxixe in the second half of each measure.

Beat #1 of each measure already has the syncopation of the basic choro rhythm. But we can also apply the choro bass rhythm to “Sounds of the Bells” by adding a 16th-note bass note at the end of beat #1. We can emphasize the maxixe’s even 8th-8th rhythm in beat #2 by adding an 8th note bass note.

PLAYING “SOUNDS OF THE BELLS” WITH AUTHENTIC STYLE

Altering the rhythm patterns, melodies, bass lines, harmonizations, and other elements of repeated measures or sections is an essential part of authentically performing Brazilian choro music. This will give your performance a “vibe” of spontaneity and give your interpretation an improvisatory flair. When “tricking out” your interpretation, keep in mind the various rhythmic patterns typical to the maxixe and choro. Use these patterns to add variety to your additions and alterations. Try to stay close to the rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic language of the time. Using modern jazz harmonizations or improvisations may detract from the authentic style of the piece.

Do you have to vary the rhythmic pattern, melody, bass line, and harmonization? No, you can play a published version as written. However, at the very least, you certainly will want to add dynamics so that the piece sounds musical.

TEMPO

Pernambuco plays “Sounds of the Bells” accompanied by Nelson Alves playing the cavaquinho on a 1926 recording on Odeon Records.

"Sounds of the Bells" with mixed rhythms.

The audio recording process was still in its infancy, and most performances were recorded directly to a wax cylinder. However, unless carefully controlled, the final recording could be slightly faster or slower than the original performance.

In Pernambuco’s recording, the pitch is slightly flat (about 48 cents or almost half a semi-tone compared to A=440 Hz international pitch standard), implying that the transfer process slowed the tempo of the performance slightly. However, it may also be that Pernambuco and Alves tuned their instruments slightly flat the day they recorded the song.

Nevertheless, a difference of 48 cents in pitch produces a negligible difference in tempo. As is, the performance starts at MM=130.7 (for an 8th note) and ends at MM=160.8! You can hear guitarists today play the piece at anywhere from 90-168 BPM for an eighth note. The options you choose to “trick out” the arrangement, your dynamics, and your technical ability will determine the best tempo for you. But I assure you, the piece sounds great at a wide variety of tempos.

In the video of Oskar and Anna Tropp dancing the maxixe, the tempo is MM=152 for an eighth note.

On the other hand, the Military Band of the State of São Paulo performs the maxixe at MM=204 for an eighth note!

RHYTHM

“It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing)” is a 1931 composition by Duke Ellington with lyrics by Irving Mills. Jazz historian Gunther Schuller characterized it as “a prophetic piece and a prophetic title.” The song became famous, Ellington wrote, “as the expression of a sentiment which prevailed among jazz musicians at the time.” Ellington credited the saying as a credo of trumpeter Bubber Miley.

As in jazz, the “swing” or “ginga” (pronounced “zheeng-gah”), as the Brazilians call it, is all-important in playing Brazilian music. In Book 1: “Fingering, Technique, and Groove, I explain how to use accents, slurs, and articulation in each measure to add ginga to your performance. In Book 2: “Tricking Out Your Interpretation, I explain how to change the rhythm patterns, melodies, bass lines, harmonizations, and other elements to infuse your performance with ginga through a “vibe” of spontaneity and improvisatory flair.

THE FORM AND STRUCTURE OF THE PIECE

“Sounds of the Bells” consists of Part 1 or Part A (measures 1-17) and Part 2 or Part B (measures 18-34). Part 1 is in D major, and Part 2 is in G major.

I found three versions of the scheme of repeats in the piece:

- The form is A-A-B-B-A in most modern editions. In other words, at the end of Part 1, there is a repeat (A-A). At the end of Part 2, there is a repeat (B-B). Then, also at the end of Part 2 (after the 2nd ending) is the notation, D.S. al Fine (back to A).

- But in the edition printed in the Revista Musical, the first section does not have a repeat, so the form is A-BB-A.

- However, in Pernambuco’s recording with Nelson Alves, they begin with a four-measure introduction. Then, they play A-A-B-B-A-A. Note that in the D.S. al Fine, contrary to typical performance procedure, they repeat Part A.

About the Pernambuco Recording

Pernambuco plays “Sounds of the Bells” accompanied by Nelson Alves playing the cavaquinho on a 1926 recording on Odeon Records. Listen to it here:

"Sounds of the Bells" with mixed rhythms.

To me, this recording has the feeling of two friends socializing and playing together on a Saturday evening or Sunday afternoon—a jam session. It is rough. It was obviously not rehearsed and was undoubtedly not an edited recording session. There are moments where the players go off the rails into near train wrecks.

Nevertheless, I believe this recording of Pernambuco and Nelson Alves captures the typical mix of rhythms, melodies, harmonies, and the spirit of the spontaneity of the maxixe and choro. Remember that these musicians had day jobs. So, they got together to play and jam and, as opportunities arose, gave performances and made recordings.

And repeating what I wrote above in TEMPO, the audio recording process was still in its infancy, and recording companies recorded performances directly to a wax cylinder. However, unless carefully controlled, the final recording could be slightly faster or slower than the original performance.

In Pernambuco’s recording, the pitch is slightly flat (about 48 cents or almost half a semi-tone compared to A=440 Hz international pitch standard), implying that the transfer process slowed the tempo of the performance slightly. However, it may also be that Pernambuco and Alves tuned their instruments slightly flat the day they recorded the song.

Nevertheless, a difference of 48 cents in pitch produces a negligible difference in tempo. As is, the performance starts at MM=130.7 (for an 8th note) and ends at MM=160.8!

Nelson Alves (Nelson dos Santos Alves) 1895-1960

One of the most important cavaquinists of the 20th century, Nelson Alves began his career in the 1910s in the Chiquinha Gonzaga Group (with the flutist Antônio Maria Passos) and in the Carioca Group (which had as a soloist Cândido Pereira da Silva, the Candinho do Trombone ). He is the probable cavaquinist on the recordings of Grupo do Pixinguinha, made between 1917 and 1922, although no document proves such participation.

From 1919 onwards, he joined the famous group Os Oito Batutas “The Eight Fearless Ones," participating in the group’s trips to France and Argentina – and in the latter country, he took part in the recordings made by the group in 1923.

According to Alexandre Gonçalves Pinto, in his book O choro, Nelson Alves, in addition to the cavaquinho, played “banjo armed in mandolin,” that is, banjo with mandolin tuning. Furthermore, as can be seen in some photos of the group Os Oito Batutas, he also played the five-string cavaquinho, a relatively common instrument at the beginning of the century but which would later disappear.

He was the author of several classic choros still played today, such as “Serpentina” and “Mistura e manda.” In addition, Alves proved to be an excellent cavaquinho soloist, recording choros of his own for Victor and Brunswick in 1929 and 1930. Nelson Alves died in Rio de Janeiro in 1960.

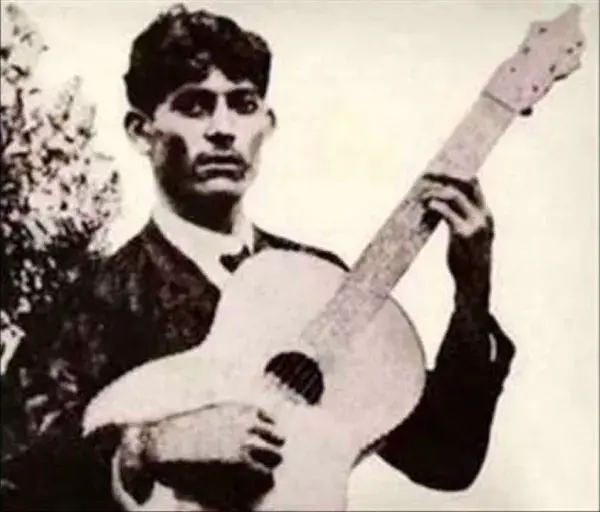

ABOUT JOÃO PERNAMBUCO

A Brief Biography

João Teixeira Guimarães is one of Brazil's most famous guitarist-composers. He was born on November 2, 1883, in the Pernambuco hinterland of Bebedouro de Jatobá, where he lived until 1895. When he was eight years old, João learned to play his first chords on the guitar with guitarist Laurindo Punga. João worked as a helper in an oxcart workshop.

In 1895 João began his itinerant journey from the Sertão (the semi-arid region of northeastern Brazil) to the Coast, going to Recife, where he continued to learn the guitar with Cirino da Guajurema, and Mané do Riachão in the surroundings of fairs and markets. In Recife, the capital of Pernambuco, he became a blacksmith by profession and guitarist by vocation.

In 1904, he migrated to Rio de Janeiro. João often told his friends and fellow musicians stories about his early life in Pernambuco and performed his musical compositions, which had solid Pernambucan roots. His friends began calling him Pernambuco, so he dropped his real name, Teixeira Guimarães, and became known to all as João Pernambuco.

“Sons de Carrilhões” stands out among the hundreds of guitar pieces by Pernambuco. He wrote it in 1912, inspired by the sounds of the oxcart chimes, which João heard constantly in his childhood in the backlands of Jatobá.

The biography above is by José Leal, a journalist, writer, poet, and music producer. Among other works, he is the author of the classic “Raízes e Frutos da Arte de João Pernambuco: Uma Infinita Viagem" (Roots and Fruits of Art by João Pernambuco: An Infinite Journey). Get Leal's book on Amazon Kindle here.

EXTENDED BIOGRAPHY, COURTESY OF THE

INSTITUTO DE ARTE POPULAR JOÃO PERNAMBUCO

João Teixeira Guimarães—João Pernambuco, was born in Bebedouro de Jatobá on November 2, 1883, son of lacemaker Teresa Teixeira Guimarães and blacksmith Manuel Teixeira Guimarães. The Teixeira Guimarães family was poor, which in addition to João was composed of José, Manoel, Maria, and Joana, who were born and lived in Bebedouro de Jatobá until 1895. They lived in the original region of the Pankararu indigenous people, a locality that later became Petrolândia.

At the age of 2, João's father died, and years later, his mother Teresa married Eugênio Alves Mendes, and from this marriage, three more children were born; Pedro, João Elpídio (Joca), and Francisca. In Bebedouro de Jatobá, at age 10, João, in addition to playing the guitar, worked as an assistant in an oxcart workshop.

In 1895, at the age of 12, João Teixeira Guimarães began his journey from the hinterland to the coast when the family moved to Recife, taking up residence in the Torre neighborhood, where his stepfather Eugênio started to work. To help his large family, João built a wheelbarrow and started to work shipping at the neighborhood fairs, at the São José Market, and around Pátio São Pedro. João continued to learn to play the guitar with guitar players such as Cirino da Gujurema, Mané do Riachão, and others. At the age of 13, with part of the money he earned from freight work, João bought an old guitar, which became his inseparable friend.

In 1904, already a blacksmith by profession and well-known as a guitarist by groups of guitar players and singers in Recife, João migrated to Rio de Janeiro, where his brothers and sisters José, Manoel, Maria, and Joana already resided. In the then Capital of the Republic, João continued developing his musical art and tempering steel, working in a foundry on Rua Frei Caneca in the neighborhood of Lapa and residing in a pension at Rua Riachuelo n° 268. The community of Lapa was the center of cultural and musical soirees in Rio de Janeiro. João often told his coworkers and musical friends stories about his origins in Pernambuco and performed his musical compositions, infused with Pernambucan roots. For this reason, he became known as João Pernambuco. He was the first musician to spread Pernambucan and Northeastern music to the general public, which later became immensely successful throughout Brazil.

Pernambuco was the first musician in Brazil to create works for solo guitar and wrote more than one hundred compositions in different musical genres. His distinctive style has its roots in the culture of both the hinterland of Bebedouro de Jatobá and the urban life of Recife. João Pernambuco was one of the great popular Brazilian guitarists alongside his friends and great guitarists Satiro Billar, Quincas Laranjeiras, and Levino Albano da Conceição. Pernambuco had no training in music theory and did not read sheet music or tablature. Nevertheless, he established himself as one of the greatest exponents of Brazilian popular guitar music.

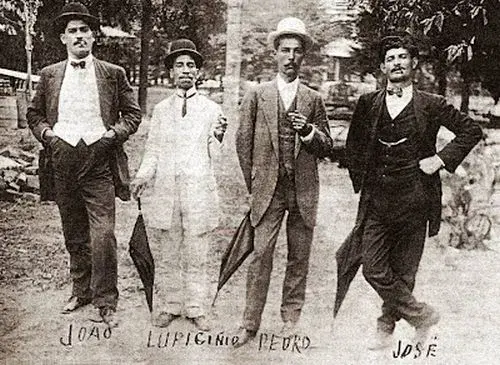

Sitting: Agustin Barrios.

O Cavaquinho de Ouro Music Store, Rio de Janeiro, 1916 or 1917.

João was a musical visionary. His technique and art of composition were ahead of their time. Some of his compositions that stand out are “Sonho de Magia,” “Caminho do Sertão,” “Pinheirada,” “Graúna,” “Reboliço,” “Dengoso,” “Interrogando,” and, of course, “Sons de Carrilhões,” music inspired by the sounds emitted by the oxcart chimes that João heard so much in his hometown of Bebedouro de Jatobá.

In addition to being a soloist, Pernambuco also formed several musical groups in Rio de Janeiro, among them Troupe Sertaneja and Turunas Pernambucanos. However, his most famous ensemble was the Caxangá Group.

From left to right, seated: João Pernambuco (Guajurema), Raul Palmieri (secretary),

and Caninha (Mané Riachão).

The Caxangá Group gave rise to the formation of the legendary Os Oito Batutas (“The Eight Fearless Ones”), a group that included musicians Pixinguimha and Donga. João Pernambuco was part of that group from 1919 to 1921.

Standing from left to right: the first unidentified, Pixinguinha, Luís Silva, Jacob Palmieri.

Seated from left to right: Otávio Viana (China), Nelson Alves, João Pernambuco,

Raul Palmieri, and Donga.

Nelson Alves (cavaquinho), Donga (guitar), not identified,

João Pernambuco (guitar), Jacob Palmieri, and not identified.

Raul Palmieri (guitar), China (guitar), Jacob Palmieri (ganzá or shaker), and José Alves.

Seated: Nelson Alves (cavaquinho), João Pernambuco (guitar), and Luiz de Oliveira (bandola).

Pernambuco worked for the City Hall of Rio de Janeiro for a few years as a paver. Then, in 1929 he began to work as a janitor in a city hall warehouse in Largo do Estácio. He also taught guitar for many years at the musical instrument store O Cavaquinho de Ouro with his countryman Quincas Laranjeiras. Laranjeiras, born in Olinda, was the creator of the first guitar method in Brazil. At Cavaquinho de Ouro, Quincas Laranjeiras’ lessons were based on his written method, whereas João Pernambuco taught by example, showing students how to play without referring to musical notation.

In the background, a painted image of Corcovado.

João Pernambuco began making his first recordings for the Odeon Seal in 1926 and the Columbia label in 1931. He also continued performing at Rádio Mayrink Veiga.

Later in 1932, Heitor Villa-Lobos took over the direction of SEMA – Superintendence of Musical and Artistic Education, an institution created to teach music and orpheonic singing. In that rich musical environment, in an inconceivable act, Villa-Lobos assigned João Pernambuco to work as an usher at SEMA.

Villa-Lobos’ action was one of the biggest disappointments experienced by the master of the Brazilian popular guitar. Despite such injustice, João Pernambuco continued his career as a guitarist and composer but gradually began to reduce his activities. Disgusted, in 1947, the 100th anniversary of the birth of poet-playwright Castro Alves, João Pernambuco composed a melody for Alves’ poem, “Canção do Vileiro,” which was his last composition. Pernambuco died on October 16, 1947.

The legacy of João Pernambuco continues to permeate Brazilian popular musical art. In addition, many memorials pay tribute to Pernambuco. Streets bear his name, and in 2021, civic leaders founded the Instituto de Arte Popular João Pernambuco in Recife. Appreciative audiences attend the “João Pernambuco Choro Festival” and “The Day of Choro João Pernambuco” in Pernambuco.

The Instituto de Arte Popular João Pernambuco also organizes and supports the “MusicArte João Pernambuco” Festival, integrated with the “João Pernambuco do Sertão ao Litoral” exhibition. It also supports the production of the João Pernambuco guitar model created by luthier Marciano. The “Prêmio de Honor ao Mérito João Pernambuco” will also be instituted to be awarded to achievements of substantial importance for popular art. Furthermore, the Instituto will also create the “Memorial João Pernambuco,” which will include the erection of a statue of João Pernambuco in the region of his hometown.

SOURCES

Published Versions of “Sounds of the Bells”

The Turibio Santos and Dilermando Reis versions of “Sounds of the Bells) are published: Classics of the Brazilian Guitar, Famous Chôros Vol. 1 José Pernambuco (João Teixeira Guimarães). 11 Famous Chôros for Guitar solo. 1992 Edition Chanterelle im Musikverlag Zimmerman, Mainz.

Carlos Barbosa-Lima’s version of “Sounds of the Bells” is from Guitar International Magazine, December 1985.

Information about Pernambuco And Brazilian rhythms:

Instituto de Arte Popular João Pernambuco

José Leal is a journalist, writer, poet, and music producer. Among other works, he is the author of the classic “Raízes e Frutos da Arte de João Pernambuco: Uma Infinita Viagem" (Roots and Fruits of Art by João Pernambuco: An Infinite Journey). Get Leal's book on Amazon Kindle here.

Douglas Lora, Brazilian Rhythms Workbook, published byTonebase Guitar

Audio:

Hear more recordings of Pernambuco: Brazilian Discography Click the button "VER MAIS" at the bottom of the webpage to see more, including "Sounds of the Bells."

Videos:

Stephanie Jones plays "Sounds of the Bells"

David Russell plays "Sounds of the Bells"

Yamandu Costa plays "Sounds of the Bells"

Daniel Girdner (slow rubato version) plays "Sounds of the Bells"

Douglas Niedt Gives You His No-Risk, Nothing-to-Lose, Money-Back Guarantee

"These are the best classical guitar video/internet lessons with the finest hi-tech production on the planet. But, if you are not satisfied with a course, I will refund your money. Just tell me why you did not like it so I can make it better for others."

Douglas Niedt is a seasoned, successful concert and recording artist and highly respected master classical guitar teacher with 50 years of teaching experience. He is Associate Professor of Music (retired), at the Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City and a Fellow of the Henry W. Bloch School of Management—Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

Doug studied with such diverse masters as Andrés Segovia, Pepe Romero, Christopher Parkening, Narciso Yepes, Oscar Ghiglia, and Jorge Morel. Therefore, Doug provides solutions for you from a variety of perspectives and schools of thought.

He gives accurate, reliable advice that has been tested in performance on the concertt stage that will work for you at home.