THE SLIDE:

Its notation, execution, and the challenges of historical interpretation

"Douglas who?"

Douglas Niedt is a successful concert and recording artist and highly respected master classical guitar teacher with 50 years of teaching experience. He is Associate Professor of Music (retired), at the Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City and a Fellow of the Henry W. Bloch School of Management—Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

Doug studied with such diverse masters as Andrés Segovia, Pepe Romero, Christopher Parkening, Narciso Yepes, Oscar Ghiglia, and Jorge Morel. Therefore, Doug provides solutions for you from a variety of perspectives and schools of thought.

He gives accurate, reliable advice that has been tested in performance on the concert stage that will work for you at home.

PURCHASE AN ALL-ACCESS PASS

TO THE VAULT OF CLASSICAL GUITAR TECHNIQUE TIPS

"Hello Mr Niedt,

My name's Gretchen, and I'm so happy I purchased an All-Access Pass to the Vault. I love your awesome technique tips. I'm amazed how much I have improved my playing.

Thank you!"

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR PROVEN STRATEGIES

THAT WILL MAKE YOU A BETTER GUITARIST?

Check out the game-changing tips in my Vault—I promise they will kick your playing up to the next level.

Purchase an All-Access Pass to the Vault.

It's a one-time purchase of only $36!

You receive full access to:

- Over 180 technique tips in The Vault.

- Special arrangements of Christmas music

- Arrangement of the beautiful Celtic song, Skellig

- Comprehensive guide, How to Master the Classical Guitar Tremolo

All that for a one-time payment of only $36. Take me to the page to Purchase an All-Access Pass

THE SLIDE:

Its notation, execution, and the challenges of historical interpretation

By Douglas Niedt

Copyright Douglas Niedt. All Rights Reserved.

This article may be reprinted, but please be considerate and give credit to Douglas Niedt.

PREFACE

The first thing you need to know when deciding how to play any ornament in pre-20th-century music is that there was no "common practice." The notation and execution of ornaments varied from country to country and composer to composer.

Written instructions from long ago or ornament tables (even by J.S. Bach) cannot overcome the general shortcomings of musical notation. Rigid rules, no matter where they come from, go against the very nature of ornaments—they were often improvised and, therefore, are too free to be tamed into regularity or taught by the book.

Descriptions of ornaments are only rough outlines, and many are contradictory. It's a jungle and very frustrating to try to figure out. There is simply no definitive solution to any ornament in a given situation. Therefore, be skeptical of everything I write from here on!

If you want a short answer to how to play an ornament, I say, "Do whatever you want. Do what makes the music sound best, and do what sounds best to you. In the end, that's what counts."

IMPORTANT NOTE:

This discussion is about the slide ornament, a specific musical technique. It's important to note that the topic has nothing to do with the common guitar technique of sliding from one note to another.

THE SLIDE

The slide (Latin: circuitus; German: schleiffer (though some used this term only for descending slides); French: coulé or coulade, port de voix double (or double) is an ornament found throughout music history but particularly in music of the Baroque period.

The slide ornament consists of three notes—two auxiliary notes and the principal note. The slide serves as a melodic and rhythmic ornament, not a harmonic one like the appoggiatura.

The Ascending Slide

The ascending slide starts on a lower auxiliary note, two scale steps below the principal note. The second note is a lower auxiliary note, one scale step below the principal note. The third note of the slide is the principal note itself. The distance from note to note will usually be a half-step or whole-step. Usually, there is a slur connecting the auxiliary notes to the principal note.

Therefore, on the guitar, if the principal note is the 1st-string G, the slide would be open 1st-string E, 1st-fret F, and finally, the 3rd-fret G (all on the 1st string).

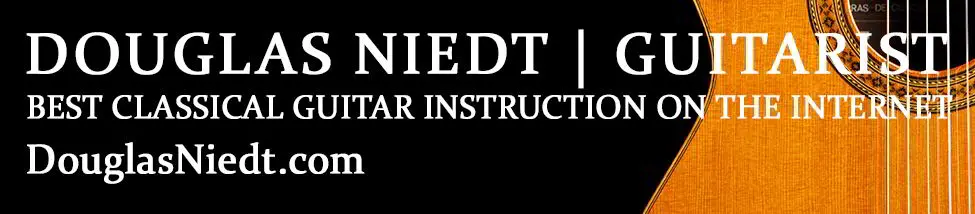

Here are some examples of note sequences for an ascending slide. Example #1:

The Descending Slide (schleiffer in German)

The descending slide (schleiffer in German) starts on an upper auxiliary note, two scale steps above the principal note. The second note is an upper auxiliary note, one scale step above the principal note. The third note of the slide is the principal note itself. The distance from note to note will usually be a half-step or whole-step. Usually, there is a slur connecting the auxiliary notes to the principal note.

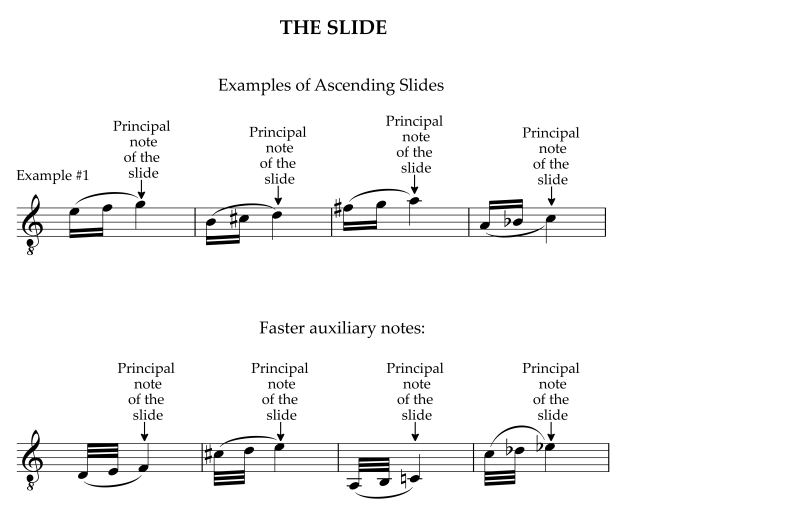

Therefore, on the guitar, if the principal note is the 2nd-string open B, the slide would be 3rd-fret D on the 2nd string, 1st-fret C, and finally, the open B (all on the 2nd string). Example #2:

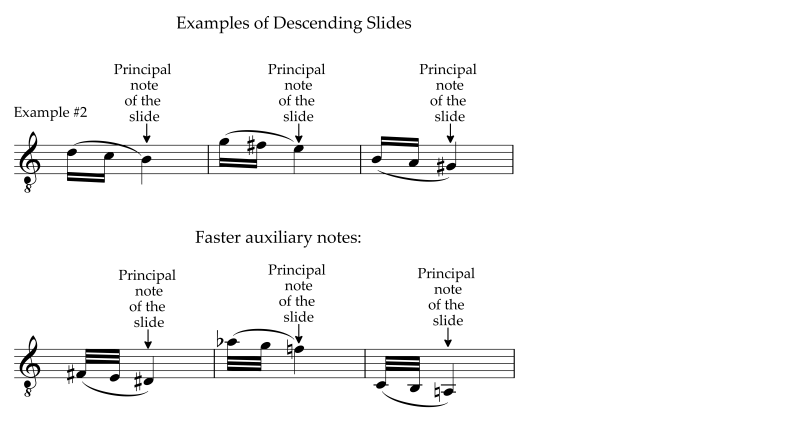

Composers occasionally write slides of more than three notes. Multitone patterns were called tirata by Italians, coulade by Frenchmen, and Pfeil by Germans. In measure 2 of the "Aria" from J. S. Bach's Cantata BWV 92 (I have given over to God's heart and mind) is an example of a four-note and five-note tirata. Example #3:

What is the Notation for the Slide Ornament?

In the Renaissance and Baroque periods, composers used several different symbols for slides. Some used a line starting and ending on a specific line or space of the staff to indicate the desired auxiliary notes. Example #4:

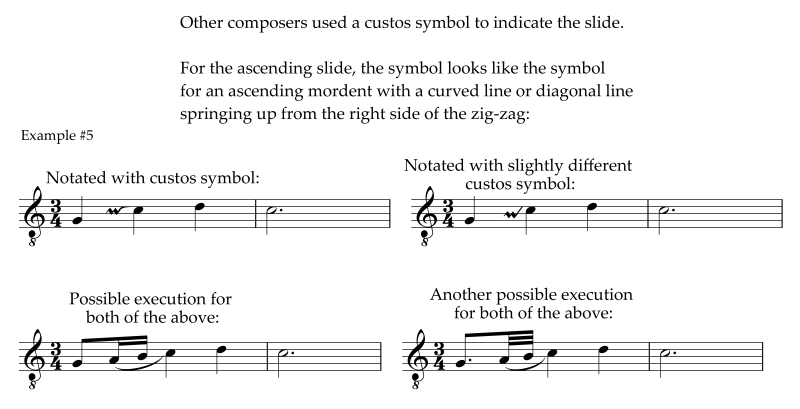

For an ascending slide, other composers, such as Johann Kuhnau, Johann Gottfried Walther (a cousin of J. S. Bach), and J. S. Bach, used a horizontal zig-zag line (like an ascending mordent or trill) with an upward diagonal or curved line springing up from the right side of the zigzag. Example #5:

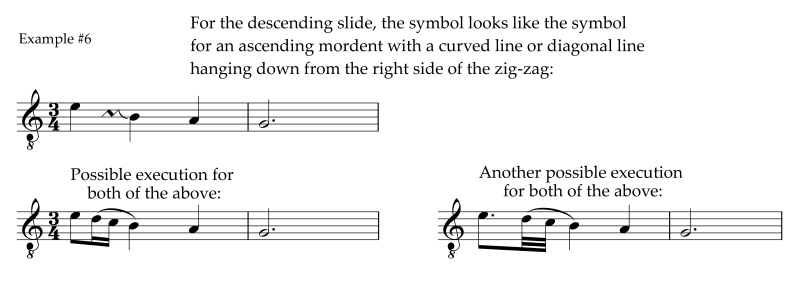

For a descending slide, Kuhnau and Walter used a horizontal zig-zag line (like an ascending mordent or trill) with a curved line hanging down from the right side of the zigzag. Example #6:

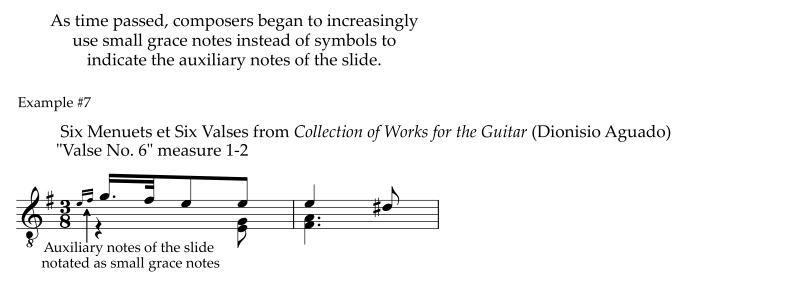

As time passed, composers began to increasingly use small grace notes instead of symbols to indicate the auxiliary notes of the slide as shown in this example from measures 1-2 of Aguado’s “Valse No. 6.” Example #7:

There are Three Ways to Accent the Notes and Execute the Rhythm of the Slide Ornament

As with most ornaments, there is no one answer to whether the Slide Ornament should start on a strong beat or before. It all depends on the date of the composition, the musical context, the composer, and the country. Sometimes, the ease of execution will offer a hint. For example, playing a slide on the beat may be technically awkward or impossible. Playing the slide ahead of the beat may sound odd. Ultimately, the individual performer must choose what sounds best to him. But here is some information to help you decide.

Slide Ornaments fall into three categories of accentuation and rhythmic execution:

- Anapestic

- Lombard

- Dactylic

The Anapestic Slide

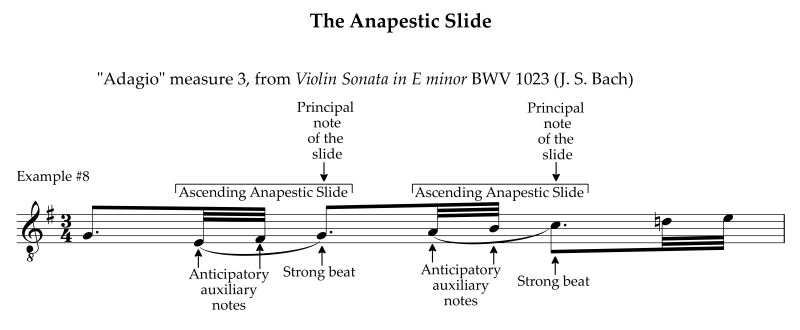

The Anapestic Slide is anticipatory. We play the auxiliary notes BEFORE a strong beat. We play the grace notes quietly and emphasize the principal note. It implies a buildup or crescendo.

The slides shown from Saint-Lambert's Les principes du clavecin in example #4 are anapestic slides. Here is an example of Anapestic Anticipatory Ascending Slides from J. S. Bach's Violin Sonata in E minor BWV 1023. Note that Bach wrote these slides in regular notation (no grace notes or symbols), so there is no doubt as to the execution. Example #8:

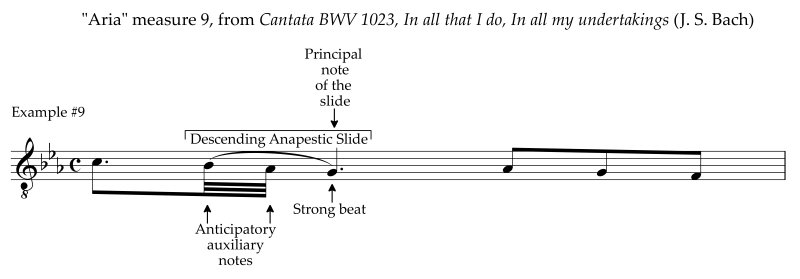

Next, here is an example of a descending Anapestic Anticipatory Slide from J. S. Bach's Cantata BWV 97 (In all that I do, In all my undertakings). Example #9:

The Lombard Slide

We execute the Lombard slide ON a strong beat. We play the first auxiliary note of the slide with a distinct accent, again, ON the strong beat. However, historical evidence shows that performers sometimes shifted the Lombard Slide slightly before or after the strong beat. But it retains its on-the-beat feel because the first auxiliary note receives the strongest accent of the ornament.

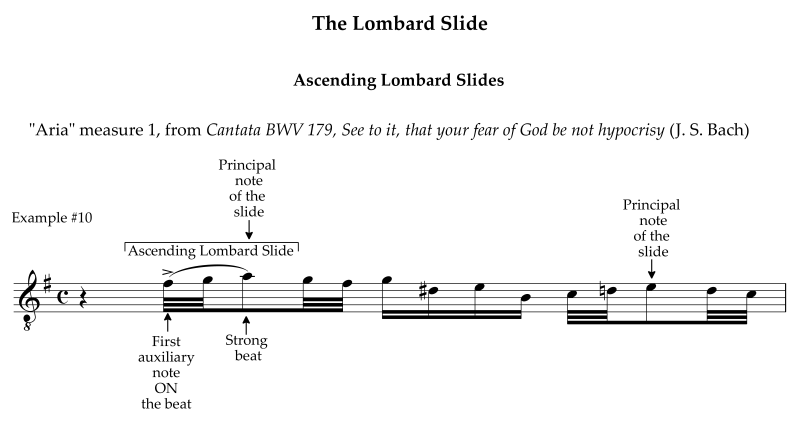

Here is an example of two Ascending Lombard Slides in J. S. Bach's Cantata BWV 179. Example #10:

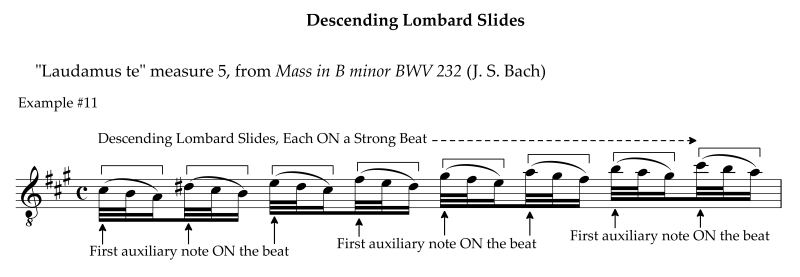

Next, here is an example of Descending Lombard Slides in the violin solo of the "Laudamus te" from J. S. Bach's Mass in B minor. Example #11:

The Dactylic Slide

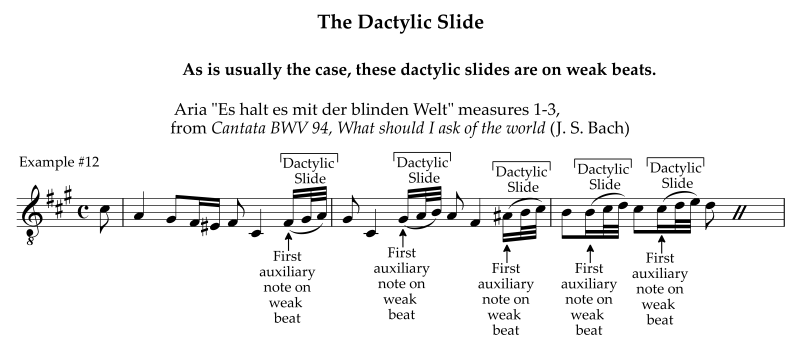

Its long-short-short rhythm sets the Dactylic Slide apart from the Anapestic and Lombard slides. The Dactylic Slide is usually anticipatory and falls most naturally on weak beats. The Dactylic Slide is unaccented, and the first auxiliary note only receives a slight emphasis. It was one of J. S. Bach's favorite melodic figures.

Here is an example of several Dactylic Slides in the oboe d'amore part in measures 1-3 of the aria "Es halt es mit der blinden Welt" from J. S. Bach's Cantata BWV 94. Example #12:

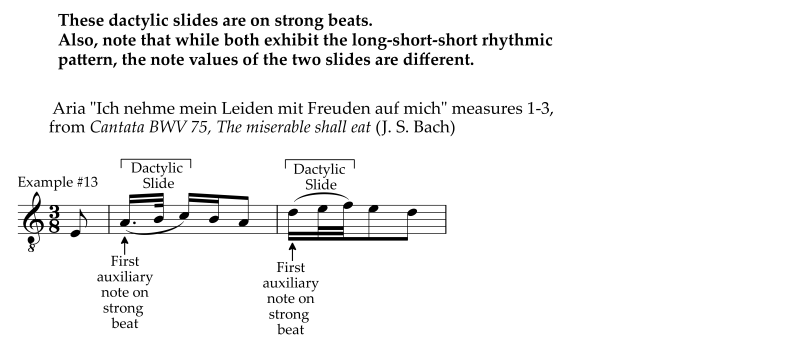

Although the Dactylic Slide usually falls on weak beats, there are exceptions. Here are two Dactylic Slides that fall on the strong beats in the oboe d'amore part in measure 1-2 of the aria "Ich nehme mein Leiden mit Freuden auf mich" from J. S. Bach's Cantata BWV 75. Also, note that while both display the characteristic long-short-short rhythm of the Dactylic Slide, the rhythmic values of the two slides are slightly different. Example #13:

How Do We Play Slides on the Guitar?

Unlike many other ornaments, guitarists only play slides using slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs). They are usually not suitable for cross-string fingerings.

Examples of Slide Ornaments in the Guitar Repertoire

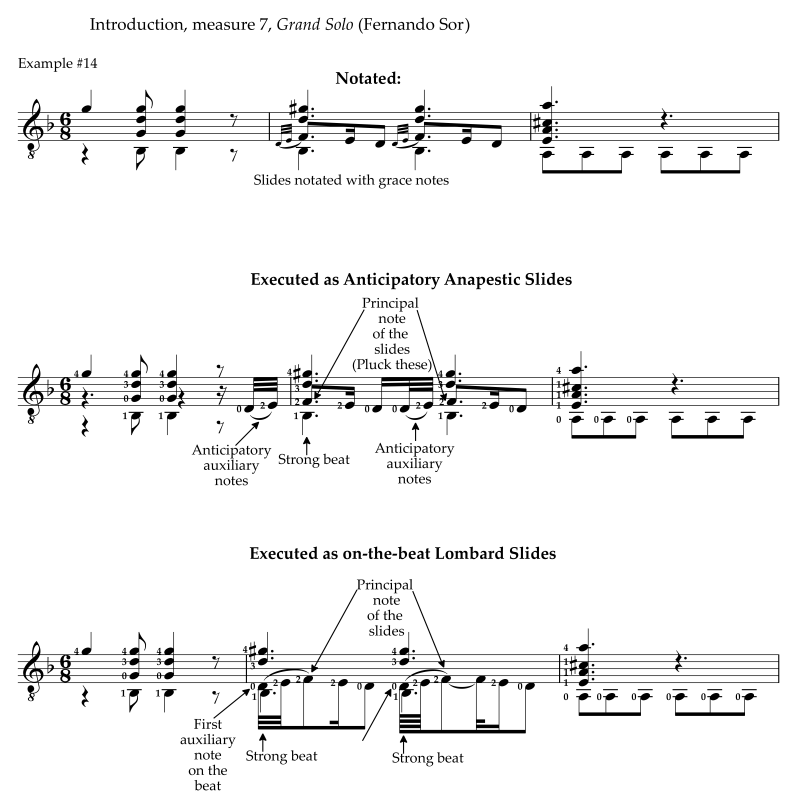

In measure 7 of the "Introduction" to Fernando Sor's Grand Solo Op. 14 (Meissonnier edition), Sor notates two ornamental slides as grace notes. We could start the slides BEFORE the strong beats as Anticipatory Anapestic Slides or ON the strong beats as Lombard Slides. Both are difficult to play. Example #14:

I prefer the Anticipatory Anapestic Slides because they emphasize the 4th-string Fs, the slides' principal note. Plus, the 4th-string Fs are the active melody note in the chords.

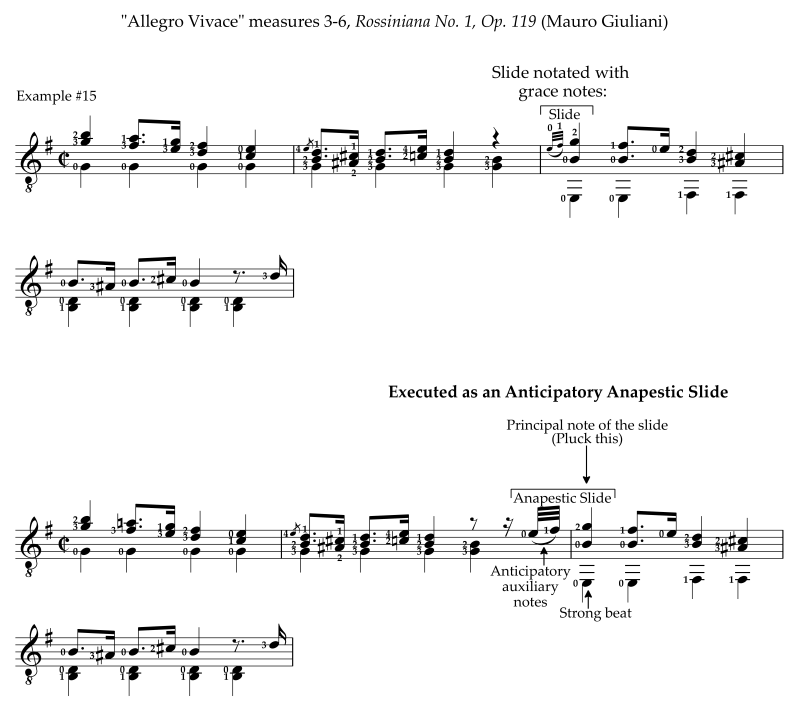

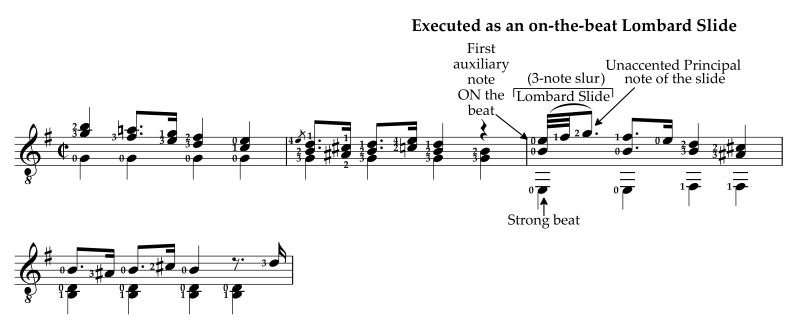

We also find examples of the slide ornament in the Rossiniana No. 1, Op. 119 by Mauro Giuliani. In measures 3-6 of the "Allegro Vivace" section, Giuliani writes a slide ornament in grace notes. Example #15:

Here again, we can play the slide ornament BEFORE the downbeat as an Anticipatory Anapestic Slide or ON the downbeat as a Lombard Slide. Italian composers favored the Lombard Slide, but in this instance, I prefer the Anticipatory Anapestic Slide. Remember, one of the qualities of the Anapestic Slide is that it implies a building up or crescendo, which fits nicely with building into and emphasizing the melodic G.

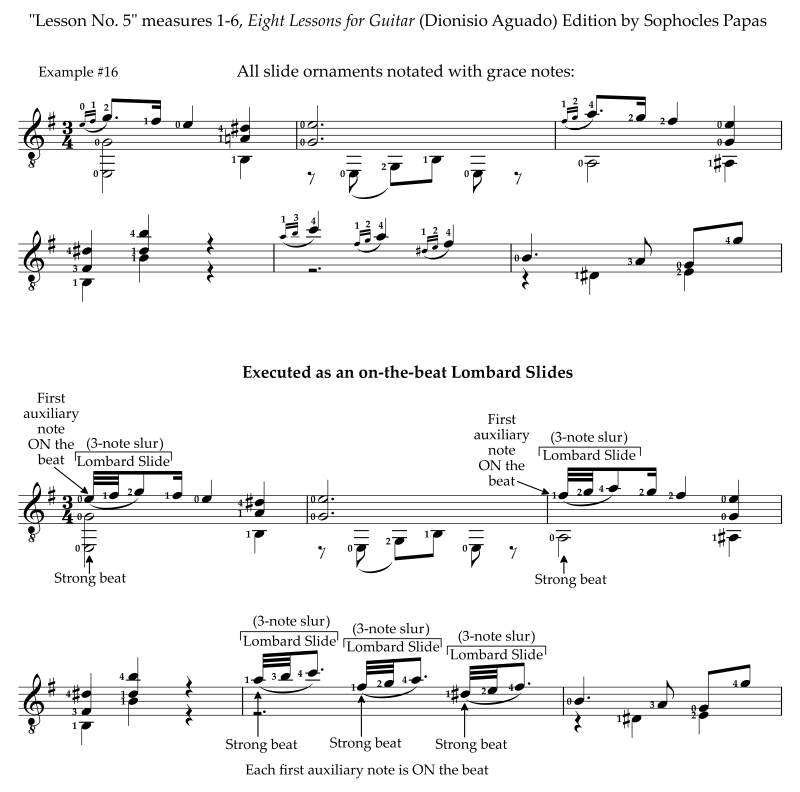

Finally, we find examples of the slide ornament in guitar composer Dionisio Aguado's works. Slide ornaments are notated in grace notes throughout his "Lesson No. 5" from Eight Lessons for Guitar. These slide ornaments sound best as on-the-beat Lombard Slides. Lombard Slides give the entrances of the ornaments a punchiness that fits the piece very well. Example #16:

Further Reading

If you want to explore any of these topics in-depth (630 pages), I highly recommend one of my favorite books, Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-Baroque Music With Special Emphasis on J.S. Bach by Frederick Neumann.

DOWNLOAD THE PDF

Download the PDF here: ORNAMENTS: THE SLIDE