THE MORDENT:

Its notation, execution, and the challenges of historical interpretation

"Douglas who?"

Douglas Niedt is a successful concert and recording artist and highly respected master classical guitar teacher with 50 years of teaching experience. He is Associate Professor of Music (retired), at the Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City and a Fellow of the Henry W. Bloch School of Management—Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

Doug studied with such diverse masters as Andrés Segovia, Pepe Romero, Christopher Parkening, Narciso Yepes, Oscar Ghiglia, and Jorge Morel. Therefore, Doug provides solutions for you from a variety of perspectives and schools of thought.

He gives accurate, reliable advice that has been tested in performance on the concert stage that will work for you at home.

PURCHASE AN ALL-ACCESS PASS

TO THE VAULT OF CLASSICAL GUITAR TECHNIQUE TIPS

"Hello Mr Niedt,

My name's Gretchen, and I'm so happy I purchased an All-Access Pass to the Vault. I love your awesome technique tips. I'm amazed how much I have improved my playing.

Thank you!"

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR PROVEN STRATEGIES

THAT WILL MAKE YOU A BETTER GUITARIST?

Check out the game-changing tips in my Vault—I promise they will kick your playing up to the next level.

Purchase an All-Access Pass to the Vault.

It's a one-time purchase of only $36!

You receive full access to:

- Over 180 technique tips in The Vault.

- Special arrangements of Christmas music

- Arrangement of the beautiful Celtic song, Skellig

- Comprehensive guide, How to Master the Classical Guitar Tremolo

All that for a one-time payment of only $36. Take me to the page to Purchase an All-Access Pass

THE MORDENT:

Its notation, execution, and the challenges of historical interpretation

By Douglas Niedt

Copyright Douglas Niedt. All Rights Reserved.

This article may be reprinted, but please be considerate and give credit to Douglas Niedt.

PREFACE

The first thing you need to know when deciding how to play any ornament in pre-20th-century music is that there was no "common practice." The notation and execution of ornaments varied from country to country and composer to composer.

Written instructions from long ago or ornament tables (even by J.S. Bach) cannot overcome the general shortcomings of musical notation. Rigid rules, no matter where they come from, go against the very nature of ornaments—they were often improvised and, therefore, are too free to be tamed into regularity or taught by the book.

Descriptions of ornaments are only rough outlines, and many are contradictory. It's a jungle and very frustrating to try to figure out. There is simply no definitive solution to any ornament in a given situation. Therefore, be skeptical of everything I write from here on!

If you want a short answer to how to play an ornament, I say, "Do whatever you want. Do what makes the music sound best, and do what sounds best to you. In the end, that's what counts."

The Mordent

The mordent (Italian, Mordente; German, Mordant; French, Pincé) is an ornament commonly found in classical guitar music.

IMPORTANT KEY POINTS ABOUT MORDENTS

- There are lower mordents and upper mordents. It is best to avoid the term "inverted" mordent because writers apply it contradictorily to both the upper and lower mordent.

- To execute the lower mordent, play the written note (the principal note), then an auxiliary note 1/2 or a whole step BELOW the principal note, and finally return to the principal note.

- To execute the upper mordent, play the written note (the principal note), then an auxiliary note 1/2 or a whole step ABOVE the principal note, and finally return to the principal note.

- We usually play mordents quickly and aggressively.

- In the Baroque period, musicians played mordents on the beat. After the Baroque period, musicians (except guitarists) began playing them before the beat.

The terminology and notation of mordents are very contradictory.

In modern times, we can accurately refer to two types of mordents: the lower mordent and the upper mordent. Example #1:

Although many writers call the lower mordent an inverted mordent, others (including the Sibelius music notation program) call the upper mordent the inverted mordent. So, it is probably best to avoid using the term "inverted" for either type of mordent. Stick with lower mordent and upper mordent.

In Bach's time, the mordent was always a lower mordent. He didn't call it a lower mordent; it was simply a mordent. Example #2:

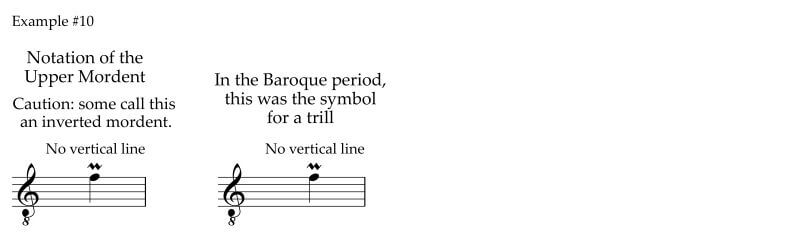

The upper mordent was out of fashion during the 17th and first half of the 18th century. Nor was there a symbol for an upper mordent. Example #3:

Bach used today's symbol for an upper mordent (a short horizontal zig-zag line placed above a note) to indicate a trill, not an upper mordent. Example #4:

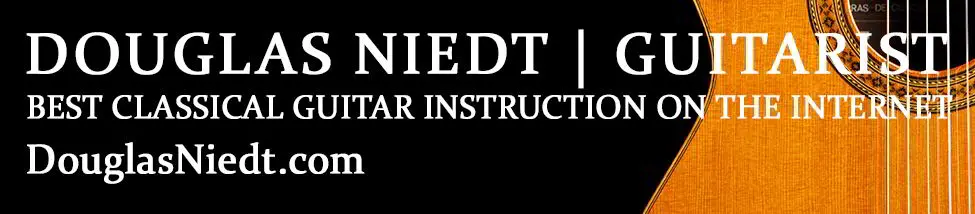

Eminent musicologist Frederick Neumann favors using the term "Schneller" for what, in modern times, we call the upper mordent. Some think of it as a miniature main-note trill (principal note, auxiliary a scale step above, principal note). Example #5:

The Difference Between the Upper Mordent and the Pralltriller

In the late Baroque period and transition to the Classical period, writers called the upper mordent either a “Schneller” or a “Pralltriller.” They used the same symbol for both, but there was a distinct difference between the two ornaments depending on context.

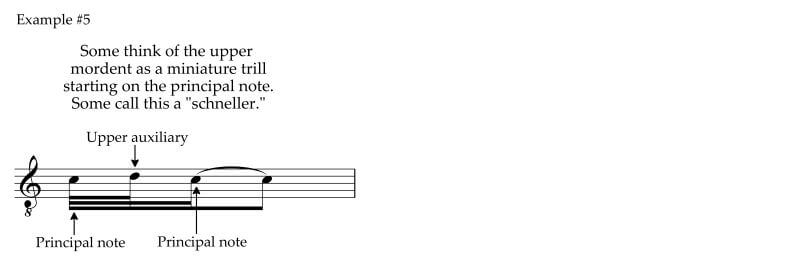

According to theorists of that time, the Pralltriller is a short, rapid, trill-like ornament of four notes, beginning on the upper auxiliary. However, it is very different from a basic trill. First of all, it occurs only on the second or lower note of a descending second. Second, it must have a tie from the note before it (the upper or first note of the descending second). Composers notated it with the same symbol used for the trill (a short horizontal zig-zag line with two "waggles." They placed the symbol above the second note of the descending second. The fact that it occurs on a descending second and that it is tied to the previous principal note makes it a pralltriller rather than a trill. Example #6:

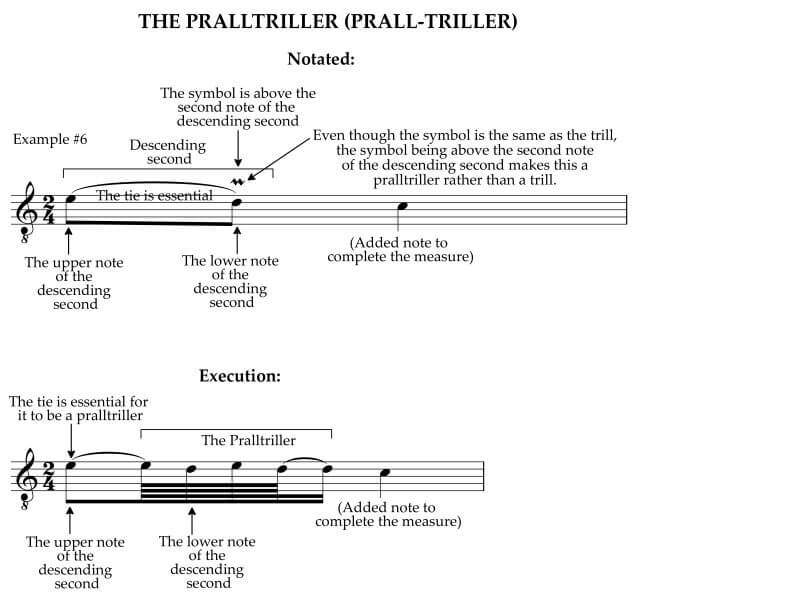

The notation of the mordent was the same, except they placed the symbol above the first note of the descending second, no tie or slur connected the notes, and the performer started the ornament on the FIRST or upper note of the descending second. For more information and musical examples, see my article about the Pralltriller. Example #7:

In the music of J. S. Bach, guitarists sometimes use the Upper Mordent or Schneller as a substitute for a standard trill in fast or technically difficult passages.

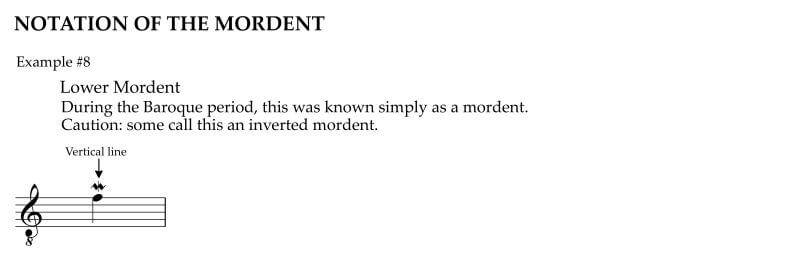

Notation of the Mordent

Composers in the Baroque period notated the mordent (later called the lower mordent) as a short horizontal zig-zag line with a vertical line through it. They placed the sign above the note. Example #8:

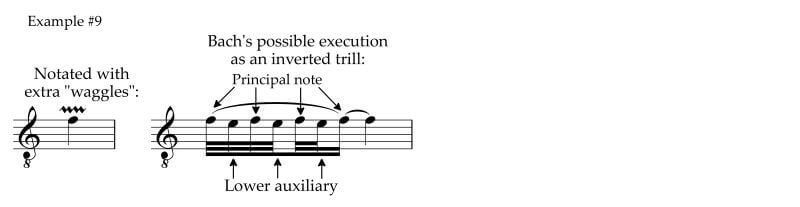

Bach tended to use two waggles, but some of his mordents had three or more, implying multiple note alternations, turning it into an inverted trill (starting on the principal note and alternating with the auxiliary one-half to a whole step below). Example #9:

Today, composers notate the upper mordent as the short horizontal zigzag with NO vertical line. Again, note that during the Baroque period, this short zig-zag horizontal line was one of the symbols for a trill, not a mordent. Example #10:

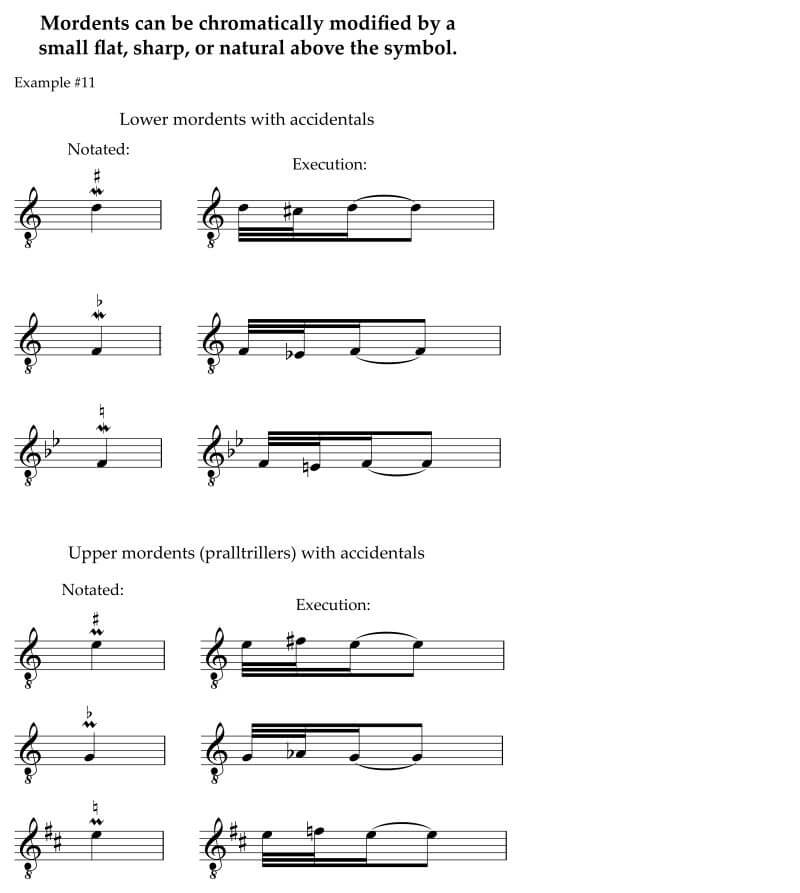

Like trills, lower and upper mordents can be chromatically modified by a small flat, sharp, or natural. Example #11:

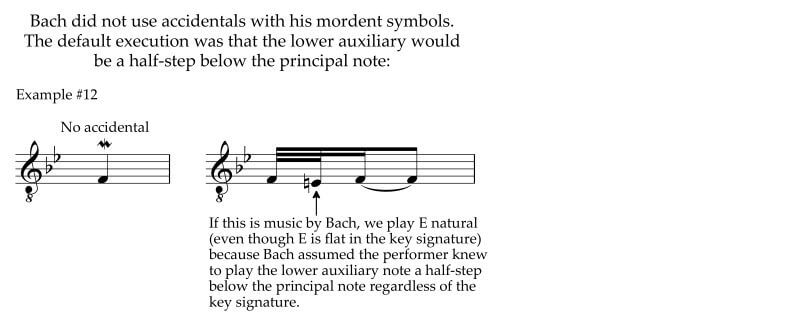

Note that J. S. Bach did not use chromatic signs on his mordent (or trill) symbols, which implies he tended to favor an auxiliary note a half-step below the principal note. Example #12:

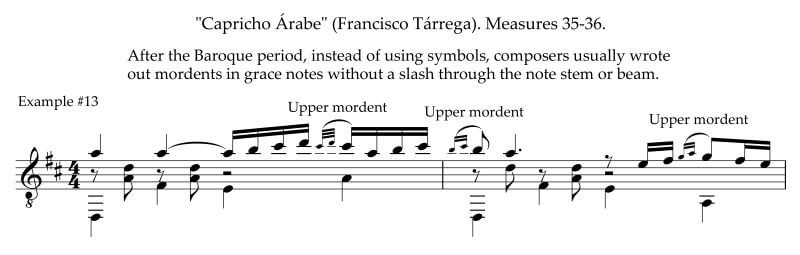

After the Baroque period, instead of using symbols, composers usually wrote out lower and upper mordents in grace notes without a slash through the note stem or beam. Example #13:

How Do We Play a Mordent on the Guitar?

The Lower Mordent

A mordent is an ornament consisting of three notes.

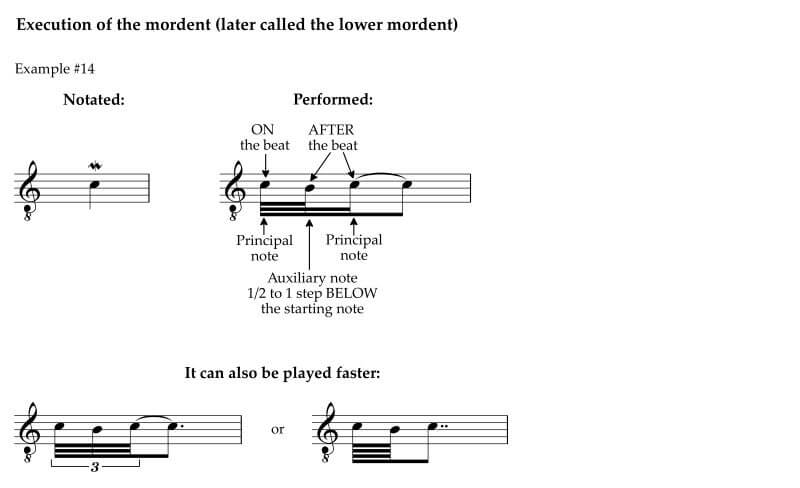

To execute the mordent, which became known as the lower mordent from the 19th century on, we play the written note (the principal note), then an auxiliary note 1/2 or a whole step BELOW the principal note, and finally return to the principal note. In Baroque music, we play the mordent ON the beat. Example #14:

However, eminent musicologist Frederick Neumann suggests that while on-the-beat execution was most common, anticipatory before-the-beat execution could be used, especially in fast passages where on-the-beat execution could be awkward or difficult.

How Fast Do We Play the Lower Mordent?

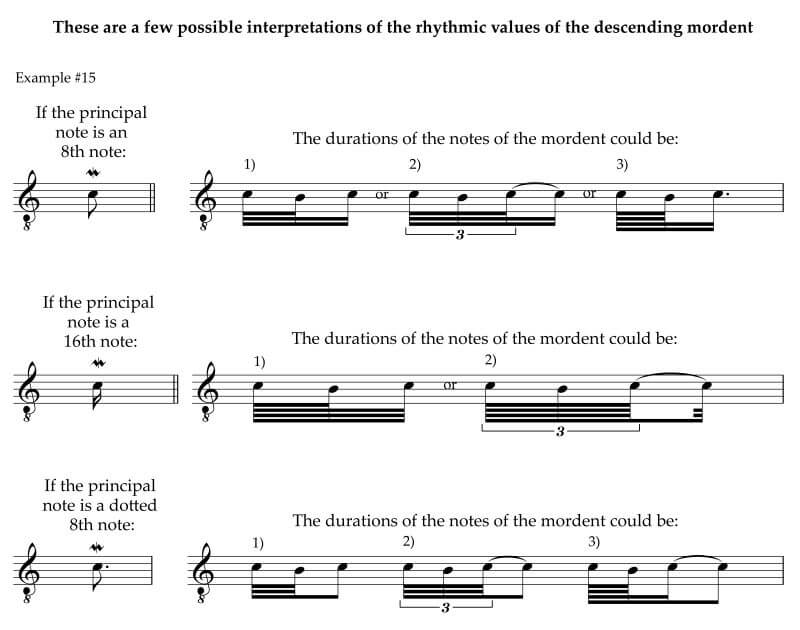

The word mordent (from the Italian mordere, to bite) implies that we should play it quickly and aggressively. But, as with other ornaments, the speed of the mordent can vary according to the tempo of the passage. Here are some sample durations for the descending mordent. Example #15:

How Do Guitarists Play the Lower Mordent?

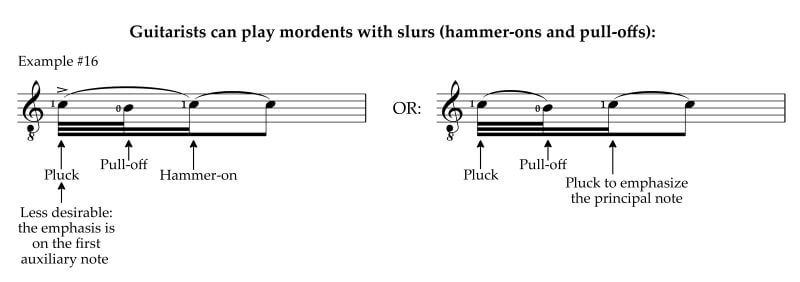

On the guitar, guitarists usually execute the lower mordent with slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs). The advantage of this method is that it is easy to do. However, it places the emphasis on the first note instead of the final principal note. To remedy that, the guitarist can slur only the first two notes and then pluck the third note for the correct emphasis. Example #16:

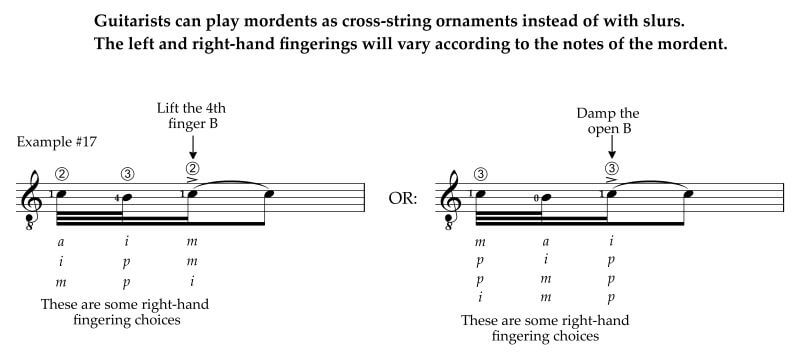

For a more aggressive “bite,” guitarists can play the lower mordent with cross-string fingerings. The cross-string fingering also gives the guitarist the ability to correctly accent or emphasize the third note. Example #17:

The Upper Mordent

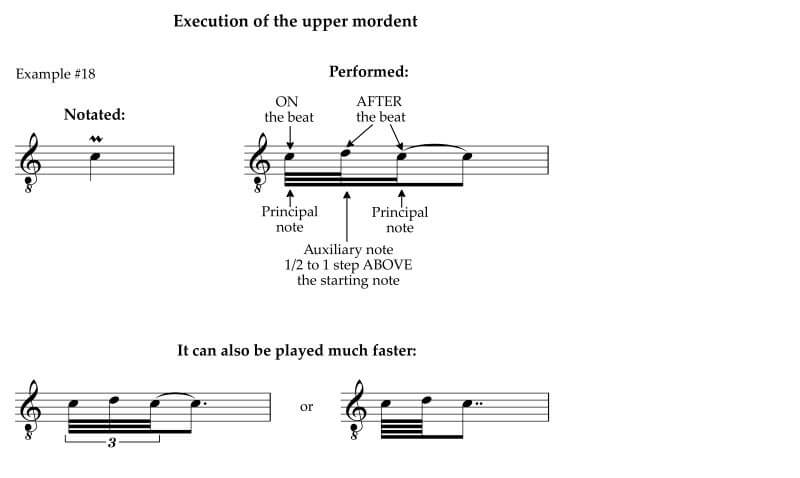

To execute the upper mordent, we play the written note (the principal note), then an auxiliary note 1/2 or a whole step ABOVE the principal note, and finally return to the principal note. Example #18:

How Fast Do We Play the Upper Mordent?

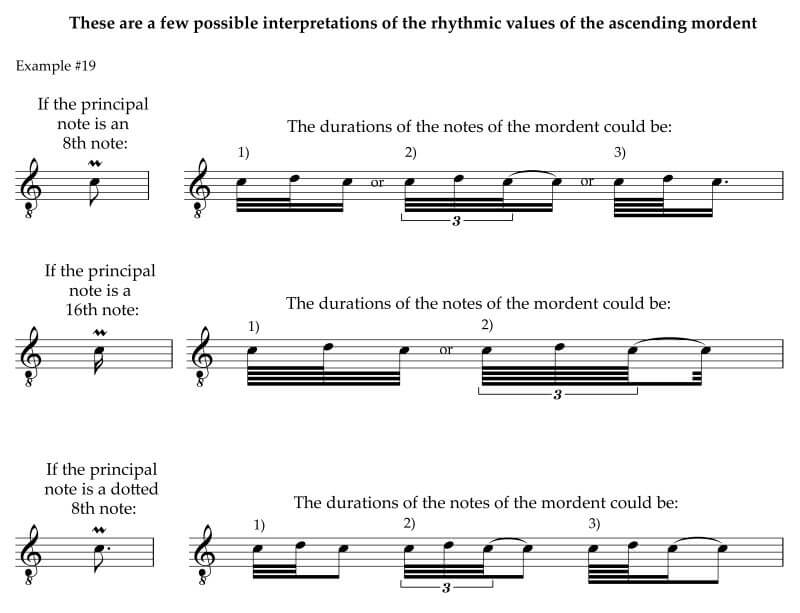

The word mordent (from the Italian mordere, to bite) implies that we should play it quickly and aggressively. But, as with other ornaments, the speed of the mordent can vary according to the tempo of the passage. Here are some sample durations for the ascending mordent. Example #19:

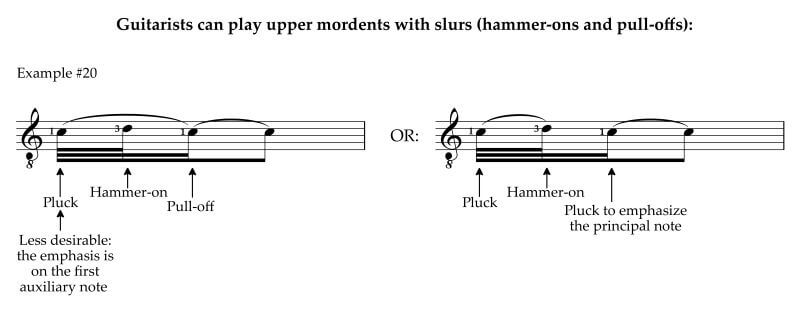

How Do Guitarists Play the Upper Mordent?

Guitarists usually execute the upper mordent with slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs). The advantage of this method is that it is easy to do. However, it places the emphasis on the first note instead of the final principal note. To remedy that, the guitarist can slur only the first two notes and then pluck the third note for the correct emphasis. Example #20:

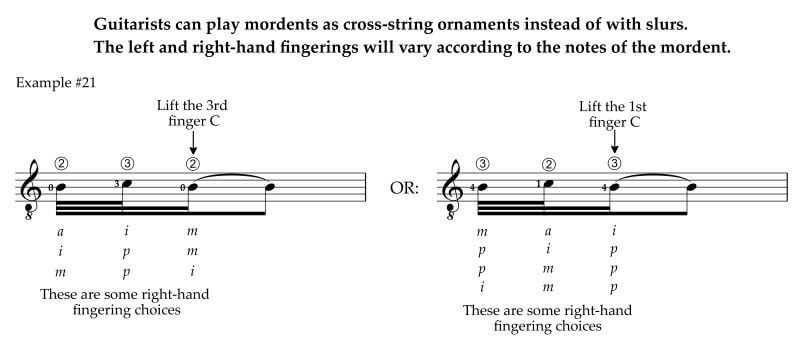

For a more aggressive “bite,” guitarists can play the upper mordent with cross-string fingerings. The cross-string fingering also gives the guitarist the ability to correctly accent or emphasize the third note. Example #21:

Mordents After the Baroque Period

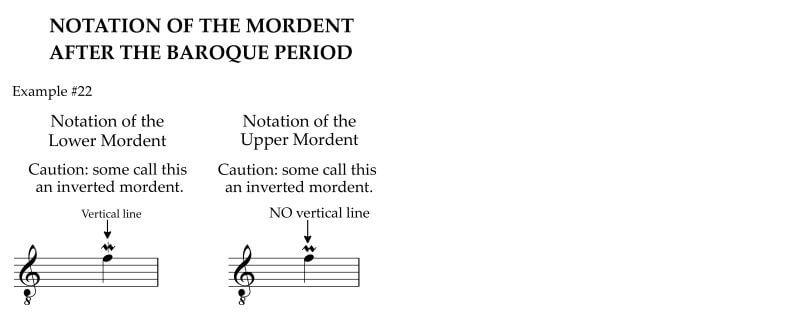

As mentioned above, after the Baroque period, the upper mordent returned to fashion. The symbol for the lower mordent remained the same (a short horizontal zig-zag line with a short vertical line through the center). However, composers adopted the short horizontal zig-zag line with NO vertical line through the center for the upper mordent. Example #22:

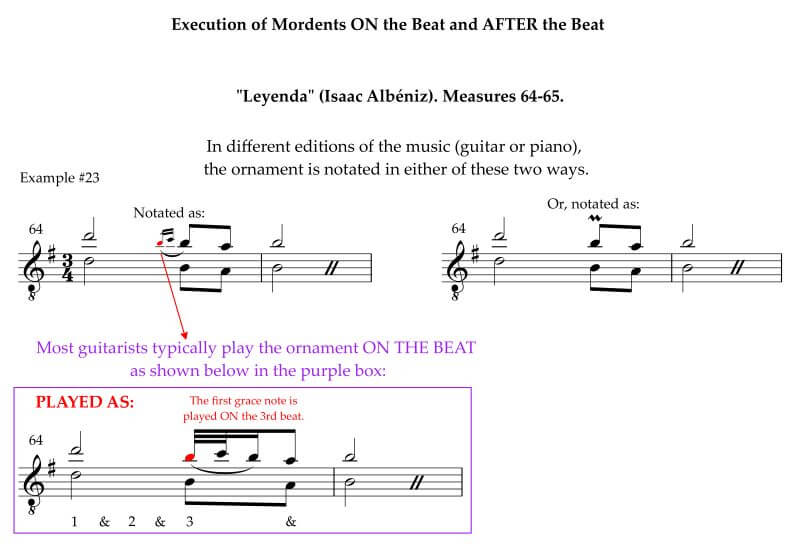

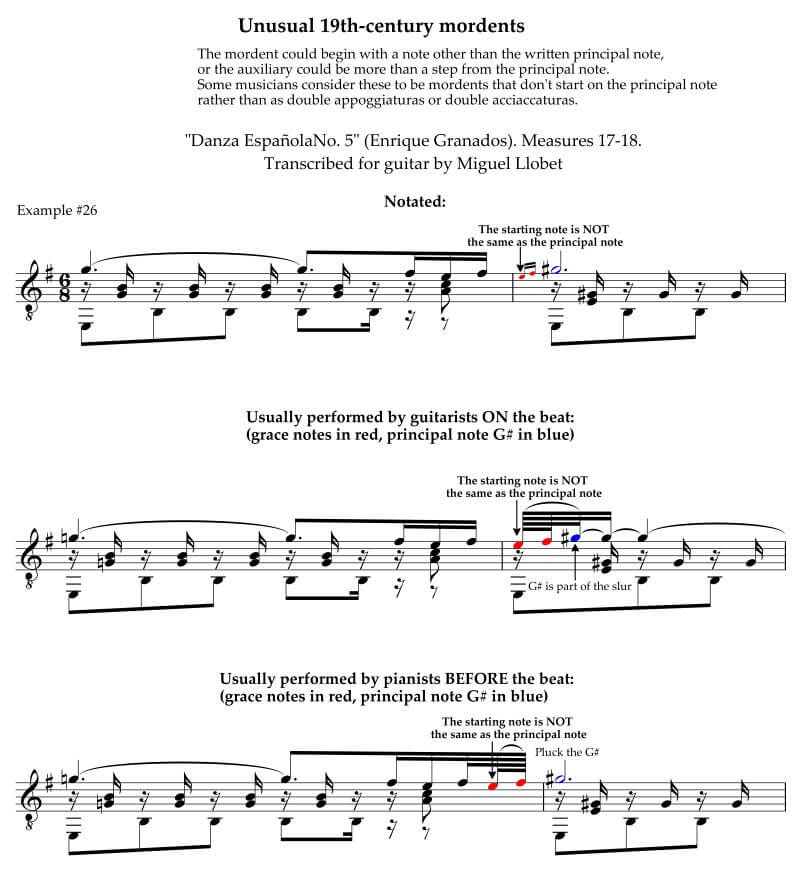

To complicate things further, beginning about 1830, instrumentalists, especially pianists, began consistently playing the first two notes of the mordent BEFORE the beat. Let's look at the middle section of "Leyenda" by Isaac Albéniz, a piece guitarists frequently perform. The next example shows two methods of notation for the mordent (from various editions) in measure 64 and the typical ON-the-beat execution guitarists use. Example #23:

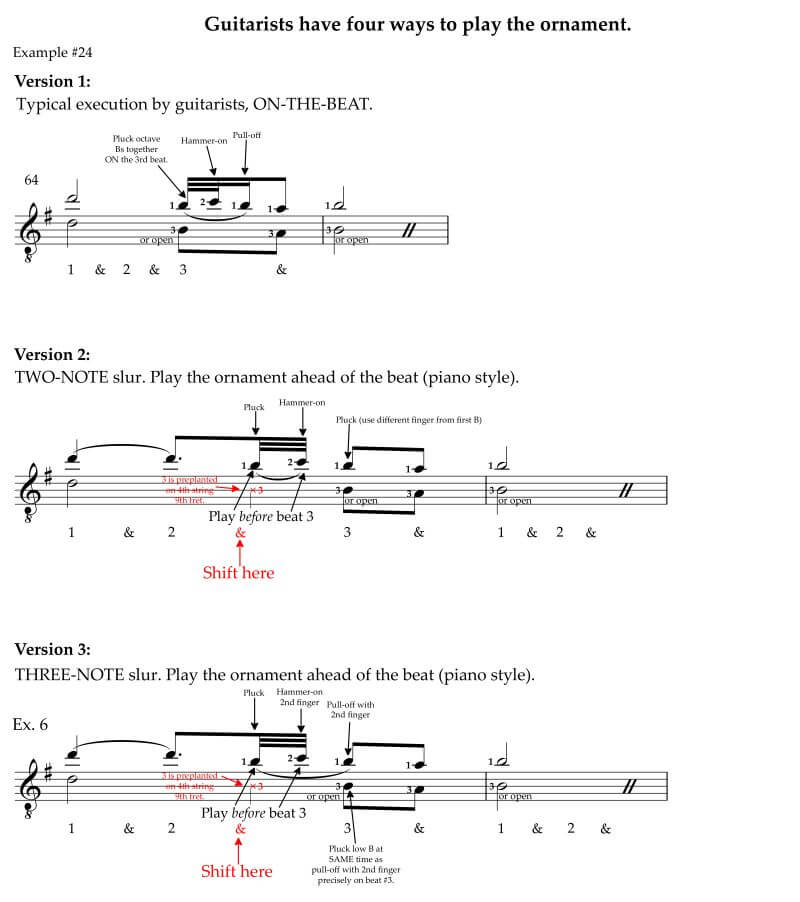

However, guitarists can play the ornament ON-the-beat, BEFORE-the-beat with a two-note slur, BEFORE-the-beat with a three-note slur, or BEFORE-the-beat with a cross-string fingering. Example #24:

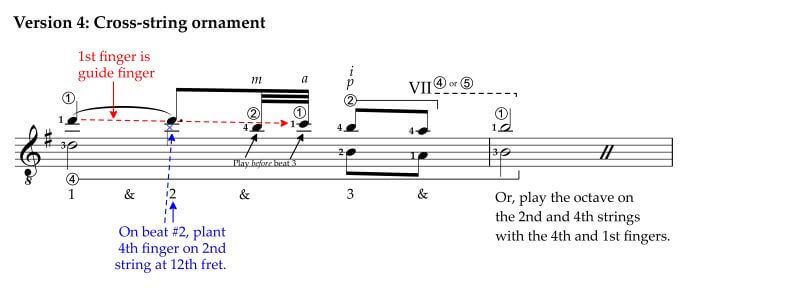

However, even as late as Chopin's music, examples abound in which the tradition of playing mordents ON the beat is still in fashion. For example, guitarists like Francisco Tárrega continued playing mordents ON the beat. Example #25:

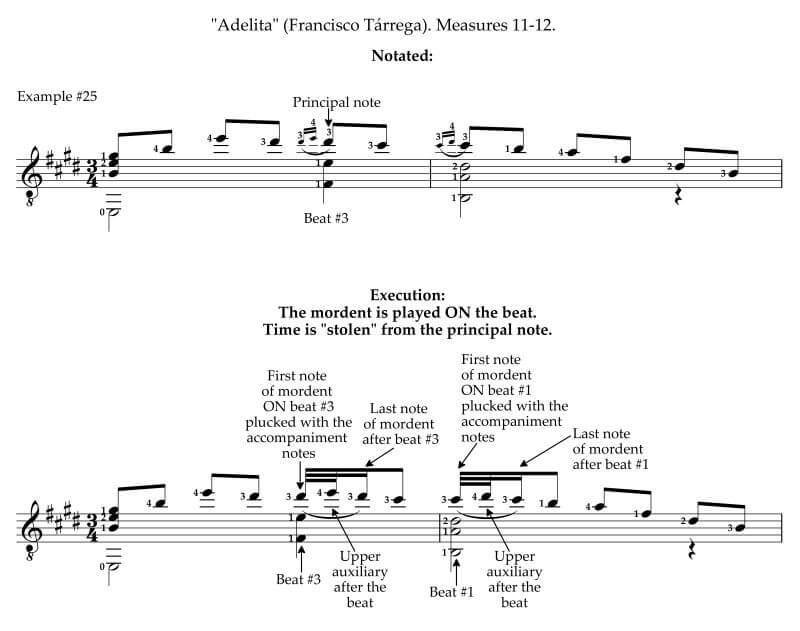

Finally, in later periods, the mordent could begin with a note other than the written principal note. However, some musicians prefer to call these instances a double appoggiatura or double acciaccatura rather than a mordent.

For example, in measure 18 of Enrique Granados’ "Spanish Dance No. 5," we have an instance of a mordent beginning a third below the principal note, followed by an auxiliary note a whole step below the principal note, and finally, the principal note. Pianists prefer to play the first two notes of this mordent BEFORE the beat, playing them in the previous measure 17, and then playing the principal note (G#) with the bass note E on beat #1 of measure 18.

Guitarists tend to play the mordent ON the first beat of measure 18 with a slur. However, guitarists also have the option of playing it piano style BEFORE the beat as pianists do. Example #26.

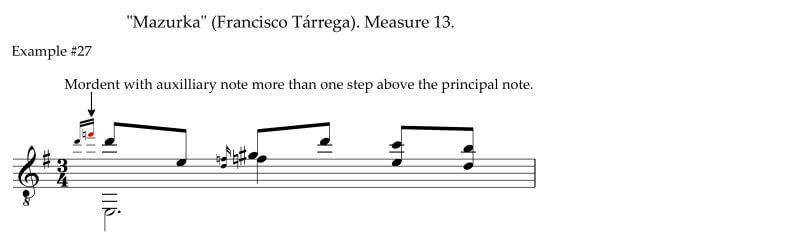

Another unusual 19th-century mordent is when the auxiliary note is more than a step from the principal note. We find an example of one of these mordents in measure 13 of Francisco Tárrega’s “Mazurka.” Example #27:

Double or Long Mordents (or pincé double)

Although we usually think of a mordent as just a single alternation between notes, in the Baroque period it was sometimes executed with more than one alternation between the indicated note and the note below, making it a sort of inverted trill. This ornament is the double mordent, long mordent, or pincé double.

Notation of the Double or Long Mordent

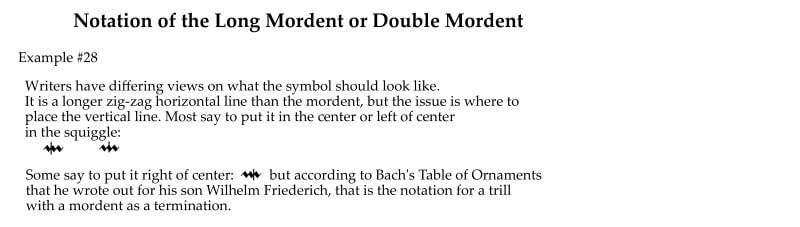

Writers have differing views on what the symbol for the double or long mordent should look like. It is a longer horizontal zig-zag line than the mordent, but the issue is where to place the vertical line. Most say to put it in the center or left of center in the zig-zag line. Some say to put it right of center. But, according to Bach's Table of Ornaments ("Explanation of various signs, intimating the way of gracefully rendering certain ornaments") that he wrote out for his son Wilhelm Friederich, right of center is the notation for a trill with a mordent as a termination. Example #28:

How to Execute the Double or Long Mordent

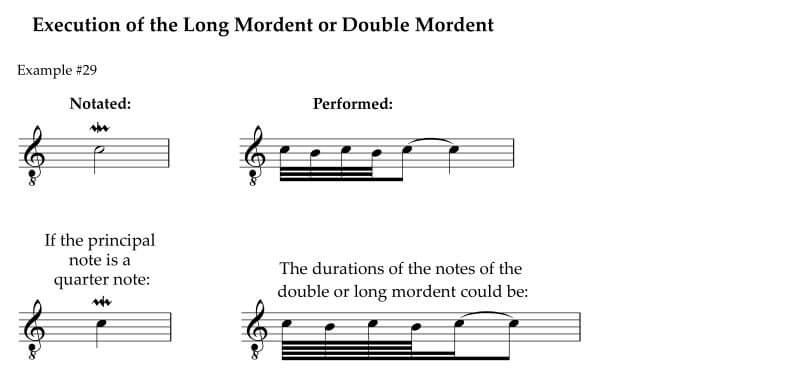

The double or long mordent (pincé double) usually consists of five notes played very quickly: the principal note, then an auxiliary note 1/2 to a whole step below the principal note, back to the principal note, the auxiliary note again, and finally, the principal note. Example #29:

The Extended Double or Long Mordent

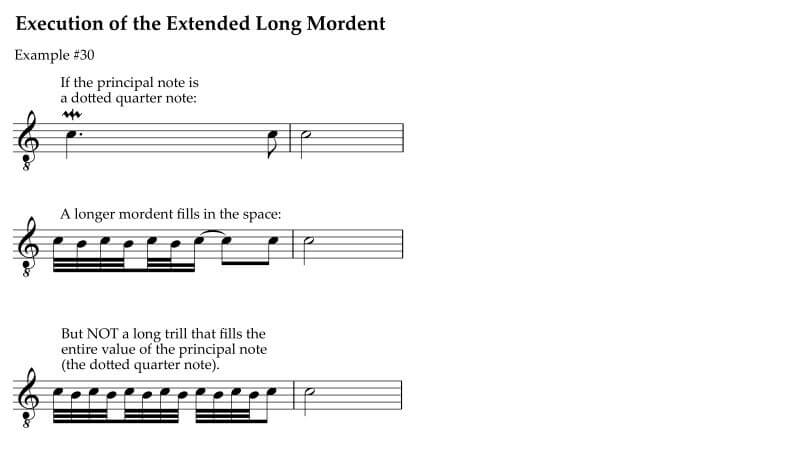

As noted above, the double or long mordent (pincé double) usually consists of five notes. However, C. P. E. Bach tells us that if we apply a mordent to a note of great length, it may contain more than five notes. In other words, we can add notes to make it an extended double or extended long mordent. In addition, C. P. E. Bach tells us that the extended double mordent must never fill up the entire value of the note, as the trill does. There must be time for a sustained principal note at the end. Example #30:

Further Reading

If you want to explore any of these topics in-depth (630 pages), I highly recommend one of my favorite books, Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-Baroque Music With Special Emphasis on J.S. Bach by Frederick Neumann.

Cross-String Ornaments

Mordents (and many other ornaments) may be executed with slurs (hammer-ons and pull-offs) or as cross-string ornaments. For detailed information on cross-string ornaments, see the following:

Cross-String Ornaments Part 1

Cross-String Ornaments Part 2

Cross-String Ornaments Part 3

DOWNLOAD THE PDF

Download the PDF here: ORNAMENTS: MORDENTS