Guitar Technique Tip of the Month

Your Personal Guitar Lesson

Thinking about buying a new guitar? What better gift to give yourself than a new guitar! Or maybe you want a get a guitar for your son or daughter. How do you choose a guitar? What do you look for? My article this month will help you out.

Contact Me

Do you have a question?

Comment?

Suggestion for the website?

HOW TO BUY A CLASSICAL GUITAR

By Douglas Niedt

Copyright Douglas Niedt. All Rights Reserved. This article may be reprinted, but please be considerate and give credit to Douglas Niedt.

Thinking about buying a new guitar? After all, Christmas is coming. What better gift to give yourself than a new guitar! Or maybe you want to get a guitar for your son or daughter. But how do you choose a guitar? What do you look for? What do you listen for? It’s a huge subject, but I will take a stab at it.

Factory-made vs. Luthier-made

What is the difference between a hand-made guitar, factory-made guitar and luthier-made guitar? To me, the words “hand-made” mean nothing. Every guitar is significantly handmade to a certain extent.

The factory-made guitar is made by hand but produced on an assembly-line basis. One person may make the box. Another may carve the neck. Another may place and dress the frets. Another may do the finishing. Depending on the brand, the division of labor may be greater.

The luthier-made guitar is made by one person beginning to end. A luthier-made guitar is not always better than a high-quality factory-made guitar. It depends on the luthier. However, a luthier who has been making guitars a number of years and has built a solid reputation (and today there are many of them) will turn out guitars of superior quality to any factory-made instrument.

Some guitarists like to work with a luthier because the luthier will often offer construction options. For example, Paul Jacobson, an excellent luthier here in Kansas City where I live, offers choices of soundboard woods, rosette, wood for back and sides, finish of the back and sides, finish of the neck, scale length, fingerboard width at the nut, fingerboard extensions, frets, fingerboard dots, string spacing at the nut, string spacing at the bridge, tuners, and case.

The luthier-made guitar will be significantly more expensive than a factory-made guitar. Prices will start at $3000. Most will be $5000 plus. If you want to save money, I highly recommend purchasing a used luthier-made guitar. I will talk more about that later. Factory-made instruments will usually cost less than $3000.

The difference in sound between a luthier-made guitar and a factory-made guitar is that the luthier-made instruments have greater volume, resonance, and projection and have a wider tonal and dynamic range. The best have a sound that grabs the heart and soul. As far as construction quality goes, factory-made guitars cost less because cheaper materials are used and workmanship is not as meticulous. Frets may not be finished or polished as carefully, glue joints might be messy, interior bracing may not be sanded, and small defects may be present in the finish.

Within the realm of the factory-made guitar one can find two classes of instruments—entry-level and mid-price guitars. Entry-level guitars with solid tops can be found for under $400. These are great for beginners. But even if you are a beginner, a better buy might be the mid-price category. The mid-price guitar will have better quality woods and other materials with better workmanship than the entry-level instrument. Therefore it will sound much better. You also won’t feel the need to upgrade to a better guitar as quickly as if you bought an entry-level guitar.

If you can afford a luthier-made guitar new or used, go for it. Sometimes a student will tell me, “I don’t really play well enough to deserve a fine guitar.” Baloney! True, a fine guitar won’t necessarily make you play better but you certainly, absolutely will enjoy playing and learning on a fine luthier-made guitar more than a factory-made instrument. A quality instrument inspires you to practice and excel as a musician. The downside is that you won’t be able to blame bad playing on your guitar! From now on, it’s your entire fault, not the guitar’s.

THE MOST IMPORTANT THING:

If you are an experienced player, the most important thing in choosing a guitar is to know your ideal sound.

First, educate your ear by listening to many recordings and live concerts. Your goal is to formulate in your head and imagination the sound you would like to have in the perfect guitar you would like to someday own. It is important to have that ideal sound clearly in your head. Get that ideal sound firmly implanted in your mind, body, and soul.

Then, when you shop for a guitar (or if you are shopping over a long period of time), you do NOT make A-B comparisons of this guitar to that guitar. Instead, hear that ideal sound in your head and then listen to the guitar you are testing out. You will immediately hear whether that guitar measures up to your standard, and its deficiencies will be readily apparent. When a guitar comes close to your ideal, you will know it immediately.

Whether you are experienced or inexperienced, keep these things in mind.

Ear Education

Take your time. Before doing any serious shopping, take a few months or years to listen to and play as many different guitars (in and above your price range) as possible. This is the stage of educating your ear. It takes time.

The Woods

Guitars are built with solid tops or laminated (plywood) tops. Plywood guitars sell at a very low price but they have a duller tone than guitars made of solid wood. Plywood is made with three thin layers of wood glued together like a sandwich. The top veneer might be a fine-grained wood but the lower layers will be poorer quality wood. That produces a top that is very strong and stable but not very resonant. Although a laminated top is okay for a beginner’s guitar, if possible purchase a guitar with a solid top. The solid top guitar will almost always have the superior sound quality. The best classical guitars have tops made of spruce or cedar. You can read many articles about which woods are best for various parts of the guitar. Guitarists especially argue about whether a spruce or cedar top is best. I once participated in a blind listening test of cedar vs. spruce top guitars made by the same luthier. Our group was unable to definitively distinguish between them. Again, these were made by the same luthier. Apparently there was a multitude of other variables that affected the sound of the guitars more than just the choice of wood for the top. Other than the necessity of the top being solid, not plywood, if it has the sound I am looking for, it doesn’t really matter much what woods the luthier or manufacturer used to construct it. My bottom line is how the instrument sounds.

Cosmetic Defects

Examine every inch, nook, and cranny of the guitar for cosmetic defects. If you are looking at a new guitar that has minor cosmetic defects, you can use those defects as a price-bargaining tool. Ask for a reduced price. Warning: if you buy a guitar with cosmetic defects be sure to bring them to the attention of the salesman and have him make a list of the defects. If you decide to return the instrument later, if the defects were not documented, the store could say you damaged the guitar. The store may not take the instrument back or only offer you a reduced refund. Small cosmetic defects are no reason to reject an otherwise good instrument. They don’t affect the sound of the instrument.

On the other hand, larger cosmetic defects may be indicative of poor workmanship or other problems. For example, if you are looking at a new guitar with a crack, I would pass. Chances are the woods were not aged properly and more cracking will occur.

An older, used guitar is another matter. Dings are to be expected on a used guitar. Minor dings and even significant dings do not usually affect the sound quality of the instrument. Even cracks (on the back) are not necessarily a reason to reject an older guitar. In fact, depending on when the cracks appeared, they can be indicative that the wood has settled and no further cracking is likely to occur. However, excessive wear will certainly be a price-bargaining chip in your favor.

SHOPPING

Old Is Good

As I mentioned before, luthier-made guitars are expensive. But even so, you can find good deals on used luthier-made instruments. An older guitar also has the advantage of having been broken in. The woods have settled, greatly reducing the possibility of further cracking, neck problems, and other ailments. An older guitar may need some fret work or minor repairs. But if it’s a great instrument with character, the refurbishing costs could be well worth it.

I even tend to prefer older, used factory-made guitars. The woods on old Alvarez-Yairi’s from the 1970’s and 1980’s for example tend to be of far better quality than the woods available today.

Ordering from a Luthier

To me, ordering a new guitar from a luthier is problematical and somewhat risky. Sure, it’s wonderful to have a luthier make a guitar especially for you. As I mentioned earlier, you will probably be able to customize many details to your taste. But let’s face it, you have no idea what that guitar will be like when it’s delivered. Different guitars made by the same luthier (or even a factory) will all sound different and feel different. Of course a top luthier in general produces great instruments. But guitars are made of trees! Every piece of wood is different. Many variables are at work during the construction process. Yes, a great luthier will produce great guitars. But he will also produce some mediocre guitars. Occasionally he will produce a lemon. Few want to admit this, but it’s the truth. What if the guitar you ordered turns out to be mediocre? Some luthiers won’t agree to it, but I would ask for a signed document that gives you the right of refusal and to have any deposit or payments paid back to you in full if you don’t like the guitar for any reason. I wouldn’t want to spend $8000 for a mediocre guitar. Buying my Ramirez guitars from Sherry-Brener in Chicago was fantastic because I was able to play 20-30 instruments and select the one I liked best. I knew exactly what I was getting.

Regardless of whether you are buying factory-made, luthier-made, old or new, if you don’t know what you’re doing, you can easily purchase a guitar unsuitable for your needs. Have your teacher or a friend who is an experienced classical guitarist advise you or go with you to help you choose a guitar. It might be a nice gesture to pay your teacher his hourly rate for the shopping trip.

In a retail store, sales people can sometimes be intimidating, particularly when you are a beginner. Sales pressure can ultimately result in your buying a guitar promoted by the store, but not the most suitable instrument for you. Never buy a guitar that you aren’t fully comfortable with, even if someone else tells you that it is the world’s greatest guitar. Never rush your decision. Allow yourself the time to make a choice you feel good about.

At a music store, you might luck out and get a knowledgeable salesperson who can help you. In the United States, the chances are far greater you will get a salesperson more familiar with electric guitars and steel-string guitars who has zero knowledge about classical guitars. That’s why it’s a good idea to have your teacher or trusted friend go with you. Learn the store’s return policy. Many music stores have an exchange policy rather than a full money-back return policy. That can be a problem. Also, some stores will only take a guitar back or allow an exchange under certain conditions. Be careful.

If you are shopping for a factory-made guitar, stay away from “cool” looking instruments such as odd colors or shapes. Stay away from cutaway classical guitars. A normal-shaped instrument will sound better than a cutaway 99% of the time. If the cutaway is amplified it might be okay when played amplified. But without amplification cutaways as a rule sound terrible. Buying an amplified classical is beyond the scope of this article.

If you are buying a luthier-made instrument from a dealer or from the luthier direct, again if you are inexperienced, have your teacher or an experienced classical guitarist friend advise you or go with you.

Buying on the Internet can be iffy. But the positive thing about Internet shopping is selection and availability. In many medium and small-sized cities the selection of classical guitars will be very limited or non-existent. The only way to shop will be to travel to another city or hit the Internet. When you buy on the Internet, the number one thing to do is to establish that if you don’t like the guitar, you have the right of refusal and can return the instrument with a 100% refund (not some kind of credit) with no restocking fee. If the merchant doesn’t agree to that, forget it. Free shipping on the return would also be desirable.

TESTING THE GUITAR

If you are a beginner it is a good idea to have your teacher or a friend who is an accomplished guitarist play the instrument so you can hear it and get their trusted opinion. If you are an intermediate or advanced player it is of questionable value for you to listen to someone else play the instrument, because it will sound very different in their hands than yours. If you are a good player, an instrument must be judged according to how it sounds under your fingers, your fingernails, and your touch--not someone else’s.

The Strings

A big problem in testing guitars is the strings. If you are looking at used guitars or guitars in a retail music store, the strings may be cheap or old. How in the world can you judge a guitar with worn-out strings? They will sound dead, uneven, and have intonation problems. They will definitely affect your perception of the guitar. I would strongly recommend taking some sets of a good basic string like D’Addario EJ45’s (and a string winder) with you on your shopping trip. Put the new strings on the guitars you want to test. It’s a lot of trouble, but if you are going to spend thousands of dollars on a guitar it is certainly worth the time, expense, and trouble.

The Action of the Guitar

The action and feel of the guitar is relatively unimportant. You will get used to any guitar fairly quickly. Of course this is assuming the guitar is the right size for you in terms of overall size and scale length and that the action is within standard, accepted norms. However, it’s a good idea to make sure there is enough space between the top of the guitar’s saddle and the wood enclosing it to lower the action if needed. I will explain more about action in a moment. Just remember, when choosing a guitar, ITS SOUND IS THE NUMBER ONE DETERMINING FACTOR, not its action or feel.

Check that the neck of the guitar is straight. You can check the neck’s straightness with either of these two methods:

1. Hold the guitar in a vertical position with the tail of the guitar on the ground and the soundboard facing out at your “audience”. Starting at the nut, sight along the edge of the neck on the 6th-string side. The neck should look straight.

2. Hold the guitar in normal playing position. Hold the 6th string down at the 1st fret with the left-hand first finger and at the 19th fret with the right-hand 1st finger. In the range of the 7th to 12th fret, the string should be barely above the frets, not touching them. Do the same for the 1st string.

Quality classical guitars don’t have truss rods for neck adjustment. If the neck isn’t straight, don’t buy the guitar unless you’re prepared to spend a substantial amount of money for repairs.

Whether a guitar has low or soft action or high or hard action is primarily determined by the distance of the strings above the frets. If the action is too high, the guitar will be difficult to play and will play out of tune. If the action is too low, the strings will buzz and rattle.

Most guitarists prefer the action to be as low as possible. The lower the action, the easier it will be to play. How low the action should be adjusted will depend on how forcefully the guitarist plays the instrument. In other words, the virtuoso guitarist who plays strongly to produce loads of volume will require a higher action than a beginner who plays relatively lightly.

If the guitar’s neck is straight the action can be adjusted by raising or lowering the bridge saddle, the nut, or both. Don’t try to do this yourself unless you know what you’re doing!

In his book Learning the Classic Guitar Part 1, Aaron Shearer provides the following specifications on action:

Step One: Checking the Bridge Saddle Height

1. With the first string held firmly against the 1st fret, the string should be no less than 3/32” above the top of the 12th fret.

2. With the sixth string held firmly against the 1st fret, the string should be no less than 1/8” above the top of the 12th fret.

Step Two: Checking the Head Nut Height

Use a standard automotive gap gauge to measure the distance between the strings and the 1st fret.

1. In open position (no strings held down), the distance between the top of the first fret and the first two strings should be .025”.

2. The 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th strings should be .030” above the 1st fret.

Shearer goes on to explain, these specifications produce a medium-low action suitable for the average student. As you gain experience and confidence and play with a stronger touch (you pluck the strings more aggressively), you may need a slightly higher action:

First string: 1/8” (instead of 3/32”)

Sixth string: 5/32” (instead of 1/8”)

Again, I want to emphasize that as long as the instrument’s action is within the norms, the action is a relatively unimportant element of choosing a guitar. The sound of the instrument is the most important attribute for choosing the instrument you want.

Play every note

Play every single note on the guitar rest stroke and free stroke. Fret/neck problems will sometimes only show up with one stroke or the other. When played at a reasonable volume level, no notes should buzz or have extraneous noise. As you play up each string fret by fret, the volume and fullness of each note should be as even as possible. Ideally there should be no dead notes or notes that stand out. I say ideally because it is rare for a guitar to be perfect. My Ramirez has a dead A on the 5th string 12th fret. But be particular about the 1st string. My experience is that if the notes on the 1st string are very even, the rest of the guitar is probably exceptional. In general, factory-made instruments will not be as even as luthier-made guitars.

Check the treble register

The basses on almost any luthier-made guitar are going to sound good. The trebles are the most difficult thing for a guitar maker to get right. I see expensive luthier-made guitars with poor treble-register quality. A guitar may have trebles that lack sustain, have dead or muffled notes, or have a thin bright tone with no body.

It will be difficult for the inexperienced player to judge the quality of the treble register of a guitar. But for the more advanced player or if you are purchasing a guitar costing more than $500, it is very important to check out the instrument’s treble register. I test out both factory-made and luthier-made guitars with the high-note passages from the second half of Villa-Lobos' Prelude No. 3. It really separates the good from the mediocre. I look for the singing, full, straight-to-the-soul live-concert sound of Segovia when he played slow passages in the upper register (7th-12th fret) of the 1st and 2nd strings. That sound literally captured the hearts of music listeners around the world during his long career. That is very significant. This sound is difficult to find on a factory-made instrument. The “Segovia sound” can be heard very clearly on many of Christopher Parkening’s recordings.

Volume and Projection

If you are a performer, don't be fooled by the volume of sound you hear when you are playing the instrument. This often has nothing to do with the amount of sound the audience is hearing out front. Have someone you trust listen to you play and give you feedback on the volume. Try to have them listen from a distance of at least 50 feet.

Intonation

Intonation problems may be difficult to detect. I find that most intonation problems are caused by defective strings. If a factory-made guitar seems to have poor intonation, don’t buy it. To learn how to check your guitar’s intonation, read my technique tip about How to Tune the Guitar (the first section, “First Things First”) and the accompanying video. If a used luthier-made guitar’s intonation is off but everything else about it is outstanding, you might want to consider having the intonation corrected. It can be expensive. Luthier Paul Jacobson has an excellent article about it.

WHAT IS SCALE LENGTH

The simplistic definition of scale length is the distance between a guitar’s nut and its bridge saddle or what some call its vibrating string length. But in the case of the guitar, that is not exactly correct.

For example, if the nominal scale length is 650 mm, guitar makers increase the distance from the nut to the bridge saddle by a small amount to more than 650 mm. Increasing the distance lengthens the vibrating length of the strings to improve the intonation of the fretted notes. When pressing a string down to the fret, the guitarist bends the string towards the fretboard, which slightly raises or sharpens its pitch. Lengthening the string slightly flattens the pitches, compensating for the sharpening of the notes that occurs when pressing the string down to the fret wire. The amount of compensation also varies from string to string depending on each string’s gauge and weight.

Therefore, guitars have “bridge saddle compensation,” and the compensation varies from string to string. Furthermore, some luthiers add a slight amount of compensation to the nut end of the string length. The commonplace nut-to-bridge-saddle-compensation and sometimes nut compensation are why you cannot correctly define the scale length as the distance between the nut and the bridge saddle. The vibrating length of each string is different due to the compensation.

Instead, we can properly define scale length as the distance from the nut (where it butts against the end of the fretboard) to the center of the 12th fret wire multiplied by two.

HOW DO I DETERMINE THE SCALE LENGTH OF A GUITAR?

To determine the scale length of a modern guitar (without nut compensation), measure the distance from the front edge of the nut (where it butts against the end of the fretboard) to the center of the 12th fret wire. Double the measurement, and that is the scale length of the guitar. This method negates the effects of nut-to-bridge-saddle compensation.

HOW LONG IS THE SCALE LENGTH OF A CLASSICAL GUITAR?

In the classical guitar world today, a scale length of 650 mm is the norm. Luthiers also make short-scale guitars with a 640 mm scale length. In the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, many Spanish guitars had a 660 mm string length. Ramirez guitars had a 664 mm or 665 mm string length. Some guitar makers, such as José Ramirez, thought that a longer scale length combined with other innovations would make the guitar louder and more powerful. There are many beautiful-sounding guitars with long scale lengths, but many guitarists find them hard to play.

DOES SCALE LENGTH MATTER?

Scale length is only one of many factors to consider when shopping for a guitar.

Playability and Guitar Scale Length

Scale length influences the overall feel and playability of a guitar.

- A longer scale length means a longer string, and the longer the string, the more it weighs.

- A shorter scale length uses a shorter string, which will not weigh as much as the longer string.

- A longer, heavier string requires more tension to bring it up to pitch than a shorter, lighter string.

Some players can feel the difference between a long-scale guitar’s stiffer tension and a short-scale guitar’s looser tension. They feel a difference in pressing the strings down with the left hand and also how hard they can play with the right hand (the right hand can play more aggressively on a long-scale guitar).

However, the choice of string (whether low, medium, or high tension) also affects what we perceive as playability and may supersede the effect of scale length.

As scale length increases, so does the distance between the frets. Players will feel the difference between a standard 650 mm scale length and the 664 mm or 665 mm scale length of a long-scale guitar such as a Ramirez guitar from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

On a shorter scale, the frets are closer together, making stretches and complex chord shapes potentially easier to execute for many players. Longer scales increase the distance between frets, requiring more significant hand movement and stretch to cover the same musical intervals. Therefore, shorter-scale guitars might lessen the chance of left-hand injury. If stretches are easier, navigating the fretboard will generally feel more effortless, and the player will feel more relaxed and comfortable overall.

Differences in the Sound of Different Guitar Scale Lengths

Some guitarists maintain that longer scale lengths deliver a richer low end due to the increased mass and energy of the lower frequency waves produced by the larger vibrating area of the strings.

They may also exhibit enhanced clarity and separation between notes, especially in the treble range. Guitars with shorter scale lengths often provide warmth and sweetness in the midrange frequencies but may lack some of the depth in the bass register found in longer-scaled models.

While some luthiers discount it, some players find a relationship between scale length and string sustain:

- String tension: Longer scale lengths increase string tension. Higher tension typically results in longer sustain, as the strings have more potential energy to continue vibrating.

- Bridge pressure: The increased tension of longer scales creates more downward pressure on the bridge. This pressure can improve the transfer of string vibrations to the guitar body, potentially enhancing sustain.

- Harmonic content: Longer scales produce more complex overtones, contributing to a perception of longer sustain. These harmonics decay at different rates, creating a more layered and prolonged sound.

However, others say factors such as choice of woods, bracing, design elements, and construction methods far outweigh scale length in determining the guitar’s sound quality, sustain, and volume.

Guitar Body Size and Guitar Scale Length

Many luthiers construct a smaller body for their 640 mm short-scale guitars. Some players say the smaller body or box size feels better in their arms, the right hand can reach its playing position more easily, and their legs do not need to spread apart as much as on a large-body guitar. However, other luthiers make their short-scale 640 mm guitars with normal body sizes. In other words, the size of the guitar body does not have to correlate with the scale length.

SHOULD I BUY A STANDARD SIZE, SHORT SCALE, OR LONG SCALE GUITAR?

When buying a guitar, The SOUND of the guitar should be the number one determining factor, not its action, feel, or scale length. Compared to sound, scale length is relatively unimportant. You will get used to any guitar fairly quickly, assuming the guitar is right for you in terms of general overall size (if you have small hands, do not buy a guitar with a scale length of more than 650 mm) and that the action is within standard, accepted norms.

Standard-Scale Guitars

Note that the 650 mm scale length is standard, so you will find more guitars to choose from in this category.

Long-Scale Guitars

Although long-scale guitars of 660 mm, 664 mm, and 665 mm seem to be out of fashion, this writer believes that many of the long-scale guitars from the great Spanish luthiers of the 1960s and 1970s are outstanding instruments, second to none if you have large hands and can handle them.

Players with large hands may prefer a long-scale guitar with its wider fret spacing.

More About Short-Scale Guitars (640 mm)

Some believe that short-scale length reduces power, volume, and projection. This loss can occur, in theory, because of reduced string tension or reduced body size. However, we can easily increase the string tension by using higher-tension strings. For example, a 640 mm scale guitar strung with hard tension D’addario strings will feel similar to a 650 scale strung with medium tension D’addario strings.

And again, a bigger body size does not necessarily mean more volume. Every design for whatever scale length will have an optimum body size and shape to maximize volume and sound quality.

Luthier Kenny Hill points out, “A shorter string reduces the overall tension of the instrument because, with the shorter length, the string doesn’t have to be pulled as tight to reach pitch. Maybe this is counterintuitive, but this lower tension can allow the top of the guitar to move more freely and produce more sound.”

Hill is a strong advocate of short-scale guitars. He remarks: “There may be a general perception that a 640 is a ‘little’ guitar, or underpowered and weak, but this isn’t necessarily so. Before trying it, I was skeptical, but over the years, some of the best guitars I’ve made have been 640 scale. There tends to be an added warmth, malleability of tone, and cooperative feeling in both right-hand tone production and left-hand facility. And there is no sacrifice of volume. I’ve never had anyone, including outstanding players, comment about any inadequacies in a 640 scale. They just don’t notice. In fact, I’ve seen them in ‘blind tests’ chosen above 650 scales many times.”

As far as sound goes (which is the most crucial element in choosing a guitar), the overall character of the woods, bracing, and other design elements are far more critical to creating a guitar with beautiful tone and volume than scale length. A 650 mm, 660 mm, 664 mm, or 665 mm scale length will not automatically produce more volume or better bass response than a 640 mm scale length.

Will a shorter-scale guitar make you play better? Well, you will not suddenly play like John Williams or Ana Vidovic, but if the guitar is easier to play and you can do stretches more easily, your hands and body will generally be more relaxed. They will be less subject to muscular fatigue, which may improve accuracy.

Another factor many prospective guitar shoppers forget is the distance between the strings at the nut. This distance can be an important factor that players with small hands and thin fingers should consider. Luthier Gregory Byers says, “The normal string spacing at the nut is about 43-44 mm, E to E, center to center. A person with very small hands might benefit from spacing as close as 37 mm. It is usually best to keep string spacing at the saddle unchanged since no matter how small the hands, free-stroke playing requires about the same amount of space between the strings.”

All guitarists, especially guitarists with small hands, should check out 640 mm guitars. Be sure to choose luthiers who are experienced in building shorter-scale guitars. Choose a guitar based on all of its merits, not just scale length or playability.

Do professional guitarists play short-scale guitars?

Many professional classical guitar players play a 640 mm scale guitar:

David Russell plays a 640mm scale guitar made by Matthias Dammann, a German luthier who pioneered the double-top construction.

Sharon Isbin plays a 640mm scale guitar made by Thomas Humphrey, an American luthier who invented the Millennium bracing system and the elevated fingerboard.

Ana Vidovic plays a 640mm scale guitar made by Jim Redgate, an Australian luthier specializing in lattice-braced and double-top guitars.

Pepe Romero and Xuefei Yang also lean towards the shorter 640 mm scale lengths.

A CHART TO MATCH HAND SIZE WITH GUITAR SCALE LENGTH

You can use this chart as a starting point, but you must play guitars of different scale lengths and string-spacing widths to determine the scale length that is most comfortable for you.

To measure the span of your hand, place a ruler on a flat surface. Place your little finger and thumb on the ruler. Place the rest of your hand flat on the surface. Spread the fingers apart as far as you can. Your hand span is the measurement from the tip of the little finger to the tip of the thumb.

Find your hand span measurement in the left column. The recommended scale length is in the middle column. In the right column, 4/4 refers to a full-size guitar. 7/8 refers to the largest child-sized guitar. See the second chart below for recommendations for children.

ADULT HAND SPAN | SCALE LENGTH | GUITAR SIZE |

|---|---|---|

250 mm or greater |

664 mm |

4/4 |

230-250 mm |

656 mm |

4/4 |

210-230 mm |

650 mm |

4/4 |

190-210 mm |

640 mm |

4/4 |

170-190 mm |

630 mm |

4/4 |

Less than 170 mm |

615 mm |

7/8 |

Buying a Guitar for a Child

Most people reading this article know that a child beginning to learn the guitar must have a good instrument. “We’ll start little Suzy on this Walmart guitar and if she sticks with it, we’ll get her a better one” is a terrible idea. Children usually quit the guitar not because of loss of interest or lack of discipline, but because the instrument they have is too large, too difficult to play, or sounds bad. If the child perseveres, the low-quality or too-large instrument will slow their progress dramatically. Hand injury is also likely. If that weren’t enough, the compensations their hands have to make in their formative years on such an instrument will result in bad habits that will continue into adulthood and will be difficult to correct.

The size of the guitar must fit the size of the child. Don’t buy an adult size guitar for an 8-year-old and expect them to “grow into it”. Guitars are available in ¼ size, ½ size, ¾ size, and 7/8 size. Hands down, one of the best buys in guitars for children are the ½ size Yamaha classical guitar and the ¾ size Yamaha classical. They can be purchased on Amazon.com for $120-130. They are also available through music stores. For the price, they sound amazingly good, play in tune, and are very well made. Some teachers highly recommend the Cordoba (based in California) children’s guitars. I have no experience with them so I can’t offer an opinion. They are also available on Amazon.com and music stores. Some teachers also recommend Strunal Guitars (Czech Republic). They can be purchased through Kirkpatrick Guitar Studio in Maryland.

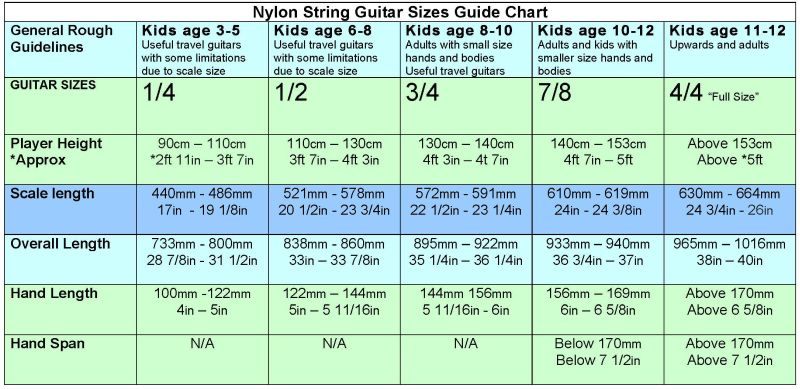

A GUIDE FOR CHILDREN: CLASSICAL GUITAR SIZES

This chart is from playableguitar.com

Buy a Case

Be sure to have a case for your guitar. Some guitars sold on the Internet and at stores are priced without the case. A good hardshell case can be purchased for $50. Prices go up quickly with the quality of the case. Some cases actually cost more than $1000! Cardboard cases and bags are the cheapest but don’t offer any real protection for the instrument. Usually a case is included with a luthier-made guitar but be sure to ask. Be sure the guitar fits in the case. If the fit is loose you can always add a towel or two so it fits snugly.

Conclusion: Choosing a Guitar is Like Choosing a Husband or Wife

Buying the perfect guitar can be like looking for that special person to be your husband or wife. When you find the right one, you will know it! In buying a guitar, your plan is to educate your ear first. Listen to recordings, go to concerts. Formulate in your head and imagination the sound you would like to have in the perfect guitar you would like to someday own. Get that ideal sound firmly implanted in your mind, body, and soul. Then when you come across THE guitar, you will know it immediately.