4. Practice the Right Hand Alone to Master Passages with Difficult String Crossings.

As you learn a new piece, it can be challenging to keep track of what your right hand is doing when you are focusing on the difficulties of the left hand. For example, learning or correcting string crossings is particularly tricky.

Here is a scale passage from Capricho Árabe by Francisco Tárrega. There are many ways to finger the scale. I like the sound of this fingering because it stays on the bass strings and only has one bad string cross, but the practice strategy I will describe applies to any fingering you choose. Example #71:

It is a fast scale. Some guitarists play it as fast as they possibly can. Others begin tentatively and make a dramatic accelerando to the end. Either way, the scale will crash and burn if we repeat a finger or make an unintended bad string cross.

To master the string crossings, first, we extract the open strings. Example #72:

Now, we can practice on the open strings. We can focus on following our right-hand fingering, so we don't repeat any fingers and play the string crosses correctly, including the bad string cross. Example #73:

Of course, practice very slowly at first. As you play the open strings, try to hear the music in your head. Sing the scale out loud.

On a problematic passage such as this, it is probably not a good idea to try to learn the complete scale at first. Instead, begin with a narrow focus.

The following steps use practice strategies called chunking, chaining, and speed bursts, which we have not studied. I will discuss these tools in detail later, but this discussion is an excellent introduction to those techniques as well. You will understand them better when you watch the video demonstration of how to practice this passage.

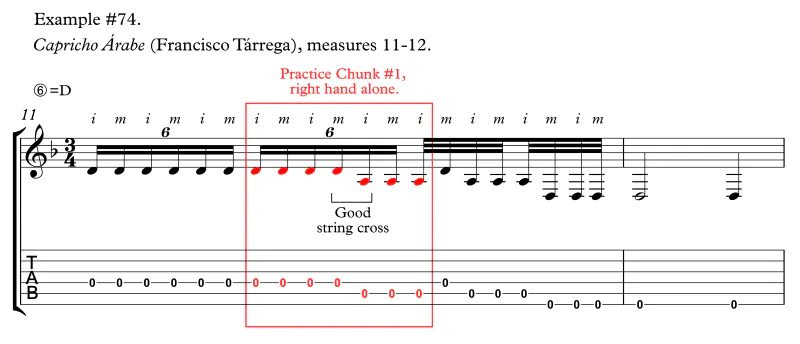

First, you might want to practice the second sextuplet to the first 32nd note of beat #3 with the right hand alone. We will call this Chunk #1. Example #74:

Play it slowly until it feels secure. Then play it very fast as a speed burst. Alternate between playing slowly and playing it as a fast speed burst.

Once that feels secure, practice Chunk #1 with both hands together. Example 75:

Play Chunk #1 slowly with both hands until it feels secure. Play it slowly enough that you don't make any mistakes. Then play it very fast as a speed burst. Alternate between playing slowly and playing it as a fast speed burst.

Then, alternate between practicing Chunk #1 with the right hand alone and both hands together. Practice slowly and with speed bursts.

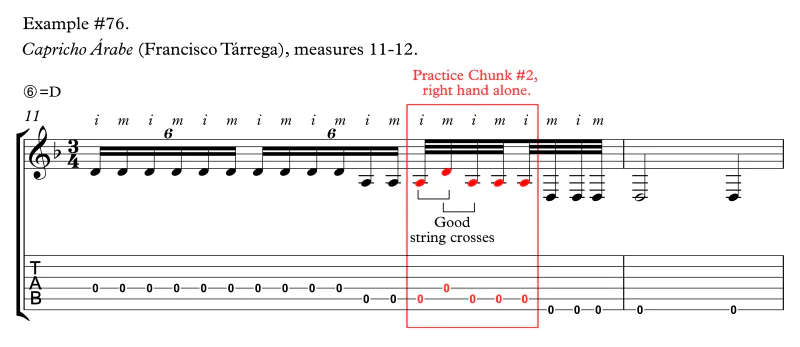

Next, practice the first five 32nd notes as Chunk #2 with the right hand alone. Example 76:

Play Chunk #2 slowly until it feels secure. Play it slowly enough that you always play it correctly. No mistakes! Then play it very fast as a speed burst. Alternate between playing slowly and playing it as a fast speed burst.

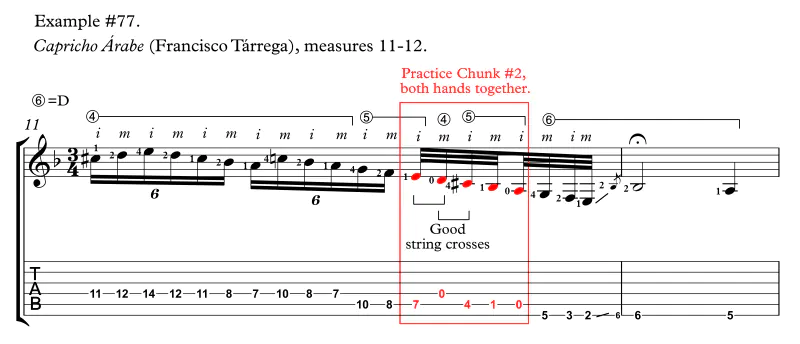

Once that feels secure, practice Chunk #2 with both hands together. Example 77:

Play Chunk #2 slowly with both hands until it feels secure. Play it slowly enough that you don't make any mistakes. Then play it very fast as a speed burst. Alternate between playing slowly and playing it as a fast speed burst.

Then, alternate between practicing Chunk #2 with the right hand alone and both hands together. Practice slowly and with speed bursts.

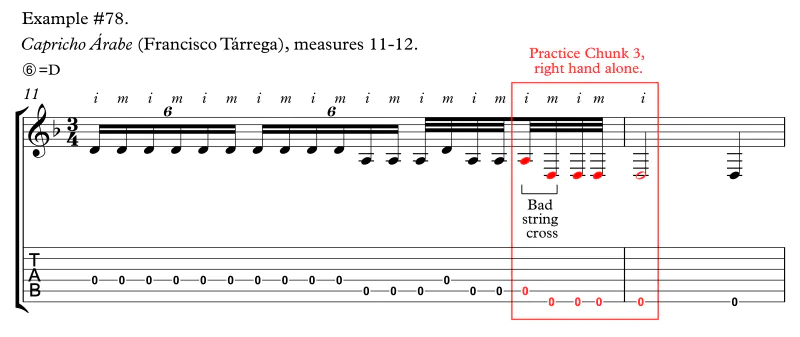

Next, practice the last four 32nd notes and the first note of measure #12 as Chunk #3 on open strings with the right hand alone. This chunk contains a bad string cross, so it will probably require extra practice. Example 78:

Play Chunk #3 slowly until it feels secure. Play it slowly enough that you make no mistakes. Then play it very fast as a speed burst. Alternate between playing slowly and playing it as a fast speed burst.

Once that feels secure, practice Chunk #3 with both hands together. Example 79:

Play Chunk #3 slowly with both hands until it feels secure. Practice it slowly enough that you play it flawlessly. Don't practice mistakes! Then play it very fast as a speed burst. Alternate between playing slowly and playing it as a fast speed burst.

Then, alternate between practicing Chunk #3 with the right hand alone and both hands together. Practice slowly and with speed bursts.

Then, combine chunks #2 and #3 together. First, practice with the right hand alone. Example #80:

Play the combined Chunk #2 + Chuck #3 slowly until it feels secure. Remember, play it slowly enough that you don't make mistakes. Then play it very fast as a speed burst. Alternate between playing slowly and playing it as a fast speed burst.

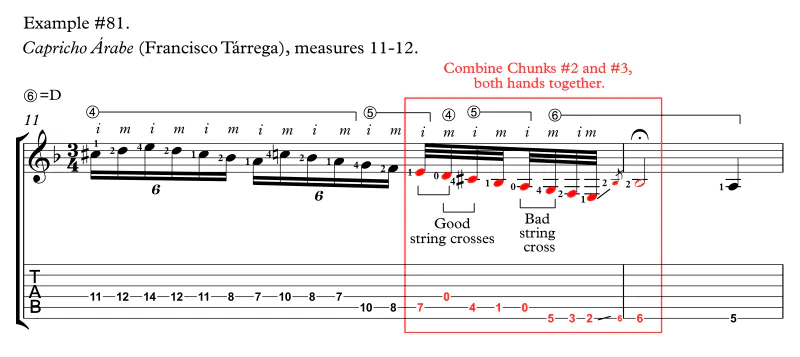

Once that feels secure, practice Chunk #2 + Chunk #3 with both hands together. Example 81:

Play the combined Chunk #2 + Chunk #3 slowly with both hands until it feels secure. Play it slowly enough that you play it correctly. Do not practice mistakes. Then play it very fast as a speed burst. Alternate between playing slowly and playing it as a fast speed burst.

Next, alternate between practicing Chunk #2 + Chunk #3 with the right hand alone and both hands together. Practice slowly and with speed bursts.

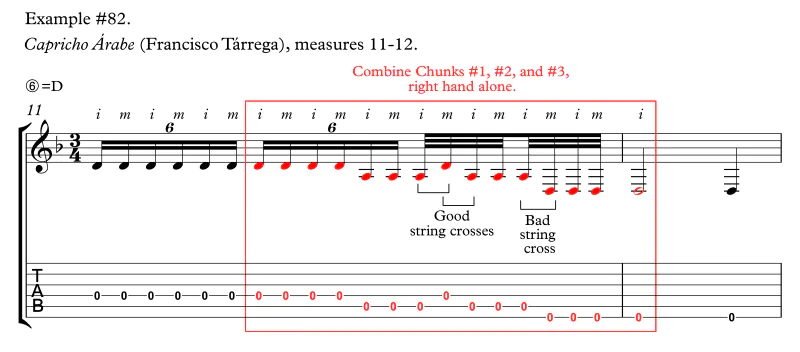

Then add Chunk #1, so you are playing Chunks #1-3 combined. Example #82:

Play the combined Chunk #1 + Chunk #2 + Chuck #3 slowly until it feels secure. Remember, play it slowly enough that you play it flawlessly. Then play it very fast as a speed burst. Alternate between playing slowly and playing it as a fast speed burst.

Once that feels secure, practice Chunk #1 + Chunk #2 + Chunk #3 with both hands together. Example 83:

Play the combined Chunks #1-3 slowly with both hands until this chunk feels secure. Do not practice mistakes! Play it slowly enough so that you play it flawlessly. Then play it very fast as a speed burst. Alternate between playing slowly and playing it as a fast speed burst.

Then, alternate between practicing the combined Chunks #1-3 with the right hand alone and both hands together. Practice slowly and with speed bursts.

Finally, add the first sextuplet, which gives you the complete scale. Practice the entire scale going back and forth between right hand alone and both hands together. Learn to switch your mental focus from hand to hand as desired. Occasionally, you may need to review specific chunks if you stumble. Break the scale down into smaller chunks and then reassemble it.

Mix it up:

- Practice some chunks right hand alone, slow.

- Practice some chunks right hand alone, fast.

- Practice the chunks both hands together, slow.

- Practice the chunks both hands together, fast.

- Tie a couple of chunks together right hand alone, hands together, slow then fast.

- Play the entire scale right hand alone, hands together, slow then fast.

- Break it back down into chunks. Practice hands separately, hands together, fast, and slow.

- Put it back together. Practice hands separately, hands together, fast, and slow.

With this practice strategy, you can master the scale in one to two weeks.

Watch me demonstrate in Video #26.

★ BE SURE TO WATCH ON FULL SCREEN. Click on the icon at the bottom on the right: