this is a blank placeholder

this is a blank placeholder

How to Learn a Piece

On the Classical Guitar

"Douglas who?"

Douglas Niedt is a successful concert and recording artist and highly respected master classical guitar teacher with 50 years of teaching experience. He is Associate Professor of Music (retired), at the Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City and a Fellow of the Henry W. Bloch School of Management—Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

Doug studied with such diverse masters as Andrés Segovia, Pepe Romero, Christopher Parkening, Narciso Yepes, Oscar Ghiglia, and Jorge Morel. Therefore, Doug provides solutions for you from a variety of perspectives and schools of thought.

He gives accurate, reliable advice that has been tested in performance on the concert stage that will work for you at home.

PURCHASE AN ALL-ACCESS PASS

TO THE VAULT OF CLASSICAL GUITAR TECHNIQUE TIPS

"Hello Mr Niedt,

My name's Gretchen, and I'm so happy I purchased an All-Access Pass to the Vault. I love your awesome technique tips. I'm amazed how much I have improved my playing.

Thank you!"

ARE YOU LOOKING FOR PROVEN STRATEGIES

THAT WILL MAKE YOU A BETTER GUITARIST?

Check out the game-changing tips in my Vault—I promise they will kick your playing up to the next level.

Purchase an All-Access Pass to the Vault.

It's a one-time purchase of only $36!

You receive full access to:

- Over 180 technique tips in The Vault.

- Special arrangements of Christmas music

- Arrangement of the beautiful Celtic song, Skellig

- Comprehensive guide, How to Master the Classical Guitar Tremolo

All that for a one-time payment of only $36. Take me to the page to Purchase an All-Access Pass

HOW TO LEARN A PIECE (SONG)

ON THE CLASSICAL GUITAR, Part 11-C

By Douglas Niedt

Copyright Douglas Niedt. All Rights Reserved.

This article may be reprinted, but please be considerate and give credit to Douglas Niedt.

*Estimated minimum time to read this article, watch the videos, and listen to the audio clips: 55 minutes.

*Estimated minimum time to read the article, watch the videos, listen to the audio clips, and understand the musical examples: 1.5-3 hours.

NOTE: You can click the navigation links on the left (not visible on phones) to review specific topics.

In Part 1, we laid the groundwork for learning a new song:

- We set up our practice space.

- We learned to choose reliable editions of the piece we are going to learn.

- We learned that it is essential to listen to dozens of recordings and watch dozens of videos to hear the big picture as we learn a new piece.

- We learned that it is important to study and analyze our score(s).

- We learned how to make a game plan for practicing our new piece.

- We learned why it is so vital NEVER to practice mistakes and the neuroscience behind it.

- We learned practice strategies to master small elements, including "The 10 Levels of Misery," which ensures we don't practice mistakes.

- We learned where to start practicing in a new piece.

- We learned that it is vital to master small elements first.

- We learned the two most fundamental practice tools—The Feedback Loop and S-L-O-W Practice.

In Part 4, we learned how to use the "Slam on the Brakes" and "STOP—Then Go" practice strategies to:

In Part 5, we learned how to practice with the right hand alone to:

- Apply planting or double-check the precision of your planting technique

- Correct or improve the balance between the melody, bass, and accompaniment

- Apply or improve string damping

- Master passages with difficult string crossings

In Part 6, we learned how to practice with the left hand alone to learn, improve, and master:

- The "lag behind" technique

- How to lift fingers to avoid string squeaks

- Left-hand finger preparation

- Synchronization of left-hand finger movements

In Part 7, we learned more on how to practice with the left hand alone to learn, improve, and master:

- Shifts

- Pre-planting the left-hand fingers

- Collapsing (hyperextending) the tip of the first finger going into and out of a bar chord

- Difficult chord changes without tiring, injuring, or "locking up" the left hand by practicing with light finger pressure

In Part 8, we began learning how to practice with Altered Rhythms. We learned the benefits and six specific strategies:

- How to practice the most common altered rhythms: dotted rhythms

- How to lengthen a particular note within each beat to alter the rhythm

- How to use extended pauses in altered rhythms to reduce tension in the hands

- How to lengthen a particular beat in each measure to alter the rhythm

- How to insert a very long pause (fermata) and play the following notes as grace notes to alter the rhythm

- How to change the accents to alter the rhythm

In Part 9, we concluded our discussion of practicing with Altered Rhythms. We learned:

- How to apply altered rhythms in divisions of 2 to a scale

- How to apply altered rhythms in divisions of 2 to a passage from a piece (not a scale)

- How to apply altered rhythms in divisions of 3 to a scale

- How to apply altered rhythms in divisions of 3 to a passage from a piece (not a scale)

In Part 10, we concluded our discussion of practicing with Altered Rhythms. We learned:

- Four-part harmony, the notation of choral music, and how that applies to the notation of voicing in guitar music

- The multi-dimensionality of music moving vertically and horizontally

- The limitations of guitar notation

- The notation of voices in guitar music

In Part 11-A, we began to learn how to practice the individual voices in a piece to:

- Learn to play the melody as the prominent part.

- Learn to find and fix flaws in the accompaniment.

- Learn to adjust the balance between the voices.

In Part 11-B, we continued our exploration of how to practice the individual voices in a piece to:

- Separate the music into its component voices so that you can examine the independent rhythms of each part and hold the notes for their correct duration.

- Practice the individual voices to learn to eliminate choppy playing and detect bad fingering.

- Practice the individual voices to help you choose whether to play a voice as a pure line (only one note ringing at a given moment) or to allow notes to ring together.

- Practice the individual voices to improve your tone quality.

- Practice the individual voices to improve the clarity of the notes within the voice (eliminate buzzes and muted notes).

HOW TO PRACTICE THE VOICES OF YOUR MUSIC

Part 11-C

In Part 11-C, we will focus on contrapuntal music and explore three more huge benefits of practicing the individual voices of your music.

Above: Autograph manuscript of the Fugue from Prelude, Fugue, And Allegro (BWV 998) by J.S. Bach

9. Practicing the individual voices is perhaps the most powerful tool you can use to improve the execution of contrapuntal passages and contrapuntal pieces such as fugues.

Many songs consist of a single melody or voice supported by a chordal accompaniment (the harmony). However, some songs, especially those from the Renaissance and Baroque periods, replace the chords with additional melodies (voices) with independent rhythms that overlap, interrupt, and support each other. Sometimes these melodies (voices) are complimentary, and other times they are not, but they still work together. Music written this way is called contrapuntal or counterpoint. The term originates from the Latin punctus contra punctum meaning "point against point," or in the case of music, "note against note." It's a fascinating, attractive sound.

At its most basic, contrapuntal music is that which contains nearly independent melodies or voices that are of equal importance. Rather than a single melody (voice) that has more weight than the chordal accompaniment (the harmony), contrapuntal music introduces two or more voices in independent rhythms that are equally important. Thus, the piece's texture is not created by supportive harmonies but by the interaction between the sometimes competing and sometimes complementary voices.

In the most basic terms, think of contrapuntal music as two or more separate tunes we play or sing simultaneously, such as "Row, row, row, your boat" or "Frères Jacques" in staggered entrances as a round.

Or, watch the "Blob Opera" sing a version by Jean-Philippe Rameau. Be patient, the second voice doesn't enter until the 26-second mark. It's a machine learning experiment from Google.

For those who wish to split hairs, and I know you are out there, the word "counterpoint" is frequently used interchangeably with "polyphony." However, polyphony generally refers to music consisting of two or more distinct melodic lines or voices. But counterpoint refers to the compositional technique involved in handling these melodic lines or voices.

Good counterpoint requires two qualities: (1) a meaningful or harmonious relationship between the lines (a "vertical" consideration—the harmony) and (2) some degree of independence or individuality within the lines themselves (a "horizontal" consideration—the melody).

Composers, especially the great ones, focus on three horizontal aspects:

- The movement of the individual melodic lines

- The long-range or overall relationships of musical design and texture (the form or structure of the piece)

- The balance between vertical and horizontal forces that exist between these lines.

The complexity can vary from two people singing "Row, row, row your boat…" or "Fréres Jacques" in staggered entrances to the grandest four-voice fugues of J.S. Bach in The Art of the Fugue.

When you play a piece containing two or more distinct parts, especially one in counterpoint, it can be difficult to hear how well you are playing voices other than the upper one. We tend to focus on what we are familiar with, usually that upper voice. Many guitarists pay scant attention to the other voices and have no idea how well or poorly they are playing them. For instance, are you playing the middle or lower voice smoothly or chopping off notes that should connect? Are the inner rhythms correct? Are you rushing some of the notes in a voice? Are you cutting off notes that should ring or letting notes ring that you should damp? When you practice a contrapuntal piece, you must be aware of all these items.

The best way to do this is to practice each voice by itself. In the case of pieces in three or four voices, we can also practice pairs of voices. Finally, we can apply the practice tools we have already learned about to make the interactions of the voices crystal clear.

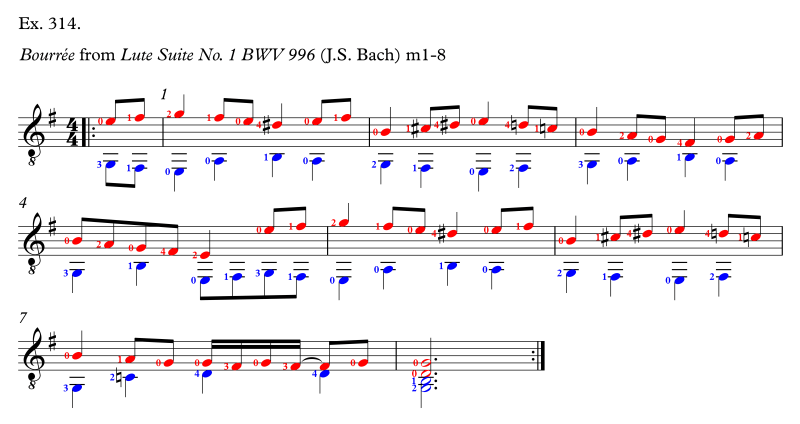

We will begin with an example most guitarists play or are familiar with—the Bourrée from Lute Suite No. 1 BWV 996. By the way, I notated the ornament in measure seven as a cross-string trill. Example #302:

A conventional left-hand fingering might look like this. Example 303:

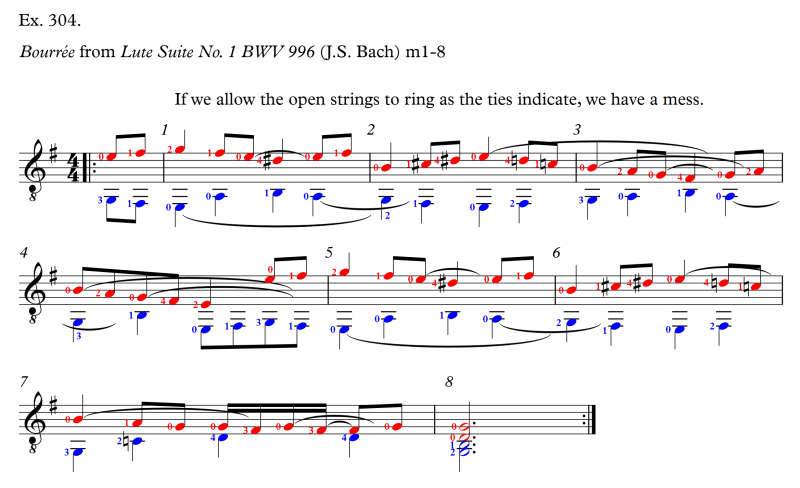

Remember that counterpoint consists of two or more LINES moving independently. You will recall our discussion that when we play a melody, we have a choice of playing it as a pure line (only one note rings at any given moment), a campanella where all the notes ring together as much as possible, or anything in between. In a contrapuntal piece, it is essential that the melody or voice be a pure line. When we allow notes to ring past other notes in the same voice, it implies a new voice. We don't want that to happen. In this conventional fingering, if we allow the open strings to ring, we end up with a mess. Example #304:

Listen to the confusion when I play both voices and allow the open strings to ring in Video #60.

Video #60: Voices ringing together, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

The most efficient way to zero in on the problems (and hear them) is to practice each voice separately. First, let's fret both voices but pluck only the soprano (upper) voice. Without any string damping, the open strings ring across the other notes in the soprano voice. This destroys the linear or horizontal dimension of the music. Example #305:

Listen to the mess I create in the passage by allowing the open strings in the soprano voice to ring in Video #61.

Video #61: Allowing open strings to ring in the soprano voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

But, I can make the upper voice a pure line if I apply string damping. Example #306:

Now listen to how clean the upper line sounds when I damp the open strings in Video #62.

Video #62: Damping the open strings in the soprano-voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Now let's follow the same process with the bass voice. Fret both voices but pluck only the bass (lower) voice. Without any string damping, the open strings ring across the other notes in the bass voice. Again, this destroys the linear or horizontal dimension of the music. Example #307:

Listen to the mess I create in the passage by allowing the open bass strings to ring in Video #63.

Video #63: Allowing open strings to ring in the bass voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

But, I can make the lower voice a pure line if I apply string damping. Example #308:

Now listen to how clean the bassline sounds when I damp the open strings in Video #64.

Video #64: Damping the open strings in the bass voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

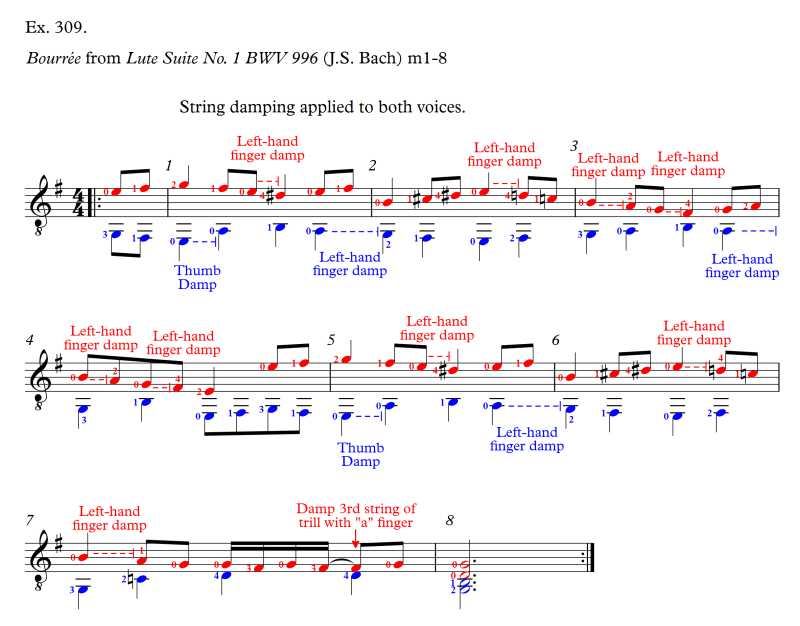

Once I master the string damping in each voice, I can put the two voices together and apply the damping. Now, I'm playing two pure lines, and the counterpoint is clear. Example #309:

On a side note, if you can avoid open strings, you can eliminate some string damping. That may be a good choice for intermediate players to make a passage easier to play. However, for advanced players, the sound should always come first. If a note sounds better open, play it open and use damping. Don't play it closed just to make it easier.

In Video #65, listen to me apply string damping to the open strings in both voices of the Bach Bourrée.

Video #65: Damping the open strings on both voices, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

10. Practice the individual voices to learn to hear each voice and how the voices interact with one another.

The goal is to increase your awareness of the voices in your music so you can hear and appreciate the intricacies, uniqueness, creativity, and wonder of the composer or arranger's work. That awareness will permeate your playing, and your listeners will also sense and hear it.

I think one of the best ways to do this is to play one voice and sing another. Let's begin with a straightforward example. In Fernando Sor's Study No. 2 (as numbered by Segovia in his Twenty Studies by Fernando Sor), we have a distinct melody in the upper soprano voice. The accompaniment, which is called an "Alberti Bass" pattern, consists of the alto and bass voices. Example #310:

A great way to hear the interaction between the melody and accompaniment is to play the accompaniment only and SING THE MELODY. Example #311:

As I point out in the next video, you are free to fret all the parts as you sing the melody or fret only the accompaniment and sing the melody. I prefer the latter because it emphasizes the independence of the two parts in my mind, hands, and fingers.

Watch me demonstrate the passage and why I'm strictly a guitarist and not a singer in Video #66.

Video #66: Play the accompaniment but sing the melody, Study No. 2 (Fernando Sor)

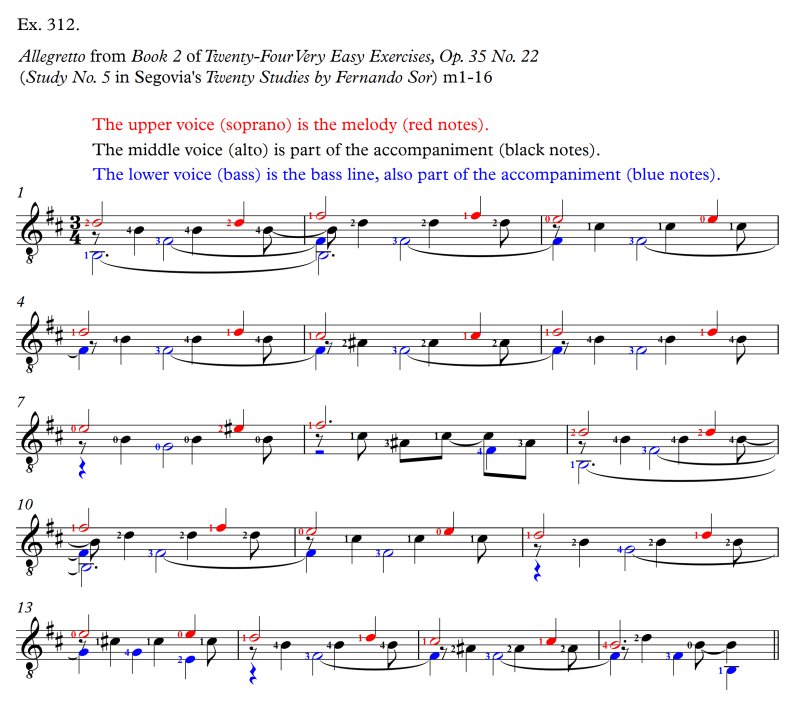

Applying the practice technique to Sor's Study No. 5 (as numbered by Segovia in his Twenty Studies by Fernando Sor) is more challenging but even more instructive. Here are the first 16 measures. Again, I separated and color-coded the three voices. Note that the alto and bass voices combine to form the accompaniment (the notes with their stems pointing down). Example #312:

Once again, we can best hear the interaction between the melody and accompaniment by playing the accompaniment only and SINGING THE MELODY. If I separate the melody from the accompaniment, it looks like this. We have the melody to sing and an arpeggio accompaniment to play on the guitar. Example #313:

Not all passages or pieces naturally lend themselves to this type of practice, but it is always worth trying.

Watch me demonstrate the passage in Video #67.

Video #67: Play the accompaniment but sing the melody, Study No. 5 (Fernando Sor)

Crank it up a notch: sing the counterpoint

Once you get the hang of it, singing the melody of a song while playing the accompaniment is very doable. But in a contrapuntal piece, singing one line while playing another can be pretty challenging. And, to play contrapuntal music well, we must learn to hear both the individual voices and how they interact. Of course, playing the individual voices is helpful, but playing one voice and singing the other is a wonderful way to hear that interaction. So let's have another look at the Bourrée from Lute Suite No. 1 BWV 996. Example #314:

I mentioned earlier that our ears tend to focus on what we know. Guitarists who play this piece or have heard it can probably sing the upper voice of the first eight measures from memory. But what about the lower voice? Can they sing it from memory? Probably not. Can they sing it while looking at the music? Doubtful. When they play the piece, they probably aren't listening to the lower voice and have no clue how well or poorly they are playing it. That is unacceptable.

Let's start the easy way. We extract the upper voice. Play and sing this voice. Example #315:

After several repetitions, try singing the line without the guitar. Wherever your singing falters, play the uncertain note on the guitar to get back on track. Keep practicing until you can sing the correct pitches in rhythm without help from the guitar.

Now comes the hard part. Sing the upper voice but play the lower voice on the guitar. You will probably need to play slowly. You have two options. Do whichever is easiest. Option #1 is to fret both parts but pluck only the lower voice as you sing the upper voice. Try to apply the string damping to the lower voice. Example #316:

Option #2 is to play only the lower voice on the guitar (don't fret the upper voice at all) as you sing the upper voice. Example #317:

Once you cease to struggle with the coordination issue, you will become more aware of the lower voice, hear it better, and become more aware of the feel and sound of the interaction between the two parts.

Watch me demonstrate the process in Video #68.

Video #68: Sing the upper voice while playing the lower voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Then we begin the challenging part of the process, which is learning to sing and hear the bass line. We extract the lower voice. Play and sing this voice. Example #318:

After several repetitions, try singing the bassline without the guitar. Wherever your singing falters, play the uncertain note on the guitar to get back on track. Keep practicing until you can sing the correct pitches in rhythm without help from the guitar.

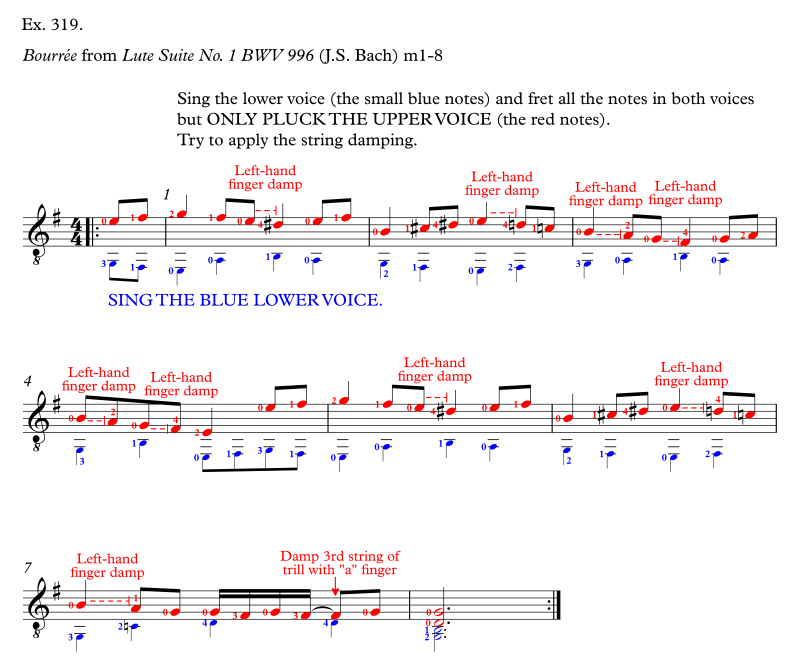

Now comes the hard part. Sing the lower voice but pluck only the upper voice on the guitar. You will probably need to play slowly. You have two options. Do whichever is easiest. Option #1 is to fret both parts but pluck only the upper voice as you sing the lower voice. Try to apply the string damping to the upper voice. Example #319:

Option #2 is to play only the upper voice on the guitar as you sing the lower voice. Example #320:

Once you cease to struggle with the coordination issue, you will become more aware of both voices, hear them better, and become more aware of the feel and sound of the interaction between the two parts.

Watch me demonstrate the process in Video #69.

Video #69: Sing the bass voice while playing the upper voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Now that you genuinely know both voices (and can sing and hear the lower voice as confidently as the upper voice), play both parts together again.

- Focus on listening to the bassline.

- Then, play it again and focus on listening to the upper voice.

- Finally, play both parts and sing. Switch back and forth from singing the upper part to singing the lower part until you feel totally comfortable with the process.

This practice procedure will enable you to hear your piece in a new light. You will now be able to hear and appreciate the intricacies, uniqueness, creativity, and wonder of the composer's work. That awareness will permeate your playing, and your listeners will also sense and hear it.

Video #70: Prelude from Cello Suite No. 1 (J.S. Bach), m1-4, played in three voices

Measures 1 through 4 are a clear example of how a passage can contain implied or hidden voices. But look at measures 22-24 from the same Prelude, where it looks like some scales and nothing more. Example #326:

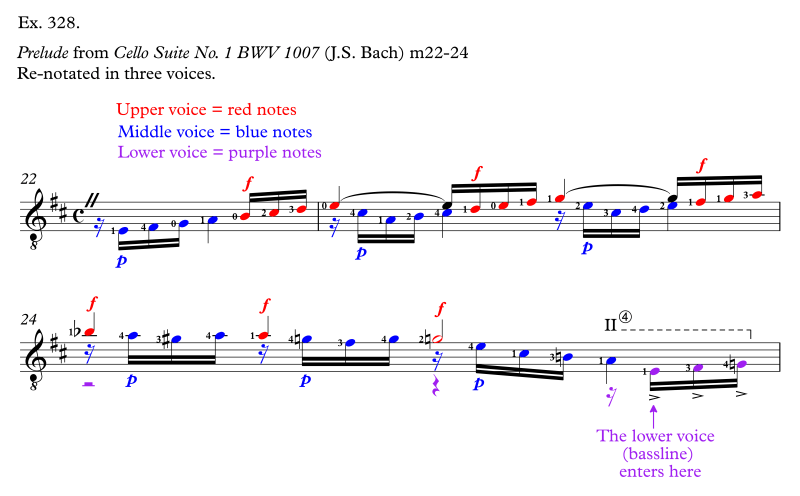

But in reality, as in the opening four measures of the piece, we have three voices, although the bassline does not enter until the last three notes of measure #24. So we can re-notate it in three voices like this. Example #327:

If we carefully re-finger the passage and add some fundamental dynamics, we can differentiate the voices more clearly. Example #328:

Listen to me play the passage as three voices in Video #71.

Video #71: Prelude from Cello Suite No. 1 (J.S. Bach), m22-24, played in three voices

The bottom line is that this entire Prelude is in three voices. Even though the cello is not an obvious choice to perform a contrapuntal work, with Bach's genius and the cellist's choice of bowing, phrasing, and dynamics, a cellist can give a strong impression that the piece is indeed in three voices. For us guitarists, it is much easier. Finding the implied or hidden voices and carefully fingering them as independent lines makes the piece sound obviously as Bach intended—a composition in three-voice counterpoint.

Hidden and implied voices occur throughout Bach's and other composers' works. An excellent example of a guitar (lute) piece with hidden or implied voices is Bach's Prelude from Prelude, Fugue, and Allegro BWV 998.

Video #72: Variations on a Theme by Handel (Mauro Giuliani), m10-17, one-dimensional interpretation

But even as you listen to me play all the notes as equals, you can hear that there is more going on than just bass notes and arpeggios. If I rewrite the passage in advanced guitar notation (stemming the notes of each voice independently), you can easily see the three voices. I color-coded them to make them even easier to see. Example #330:

Now, listen to me play the passage again, this time playing it in three voices by differentiating the relative volume of each part in Video #73.

Video #73: Variations on a Theme by Handel (Mauro Giuliani), m10-17, played as three voices

I think those measures are straightforward. Most players would catch on that the melody is embedded in the arpeggio. However, the following four measures, 18-21, are not so obvious. Here is the original notation. Example #331:

The first time I studied the passage, it looked like more arpeggios and a scale. But after playing it for a while, I began to hear three voices. Example #332:

Listen to me play the passage using some simple dynamics to bring out the three voices in Video #74.

Video #74: Variations on a Theme by Handel (Mauro Giuliani), m18-21, played as three voices

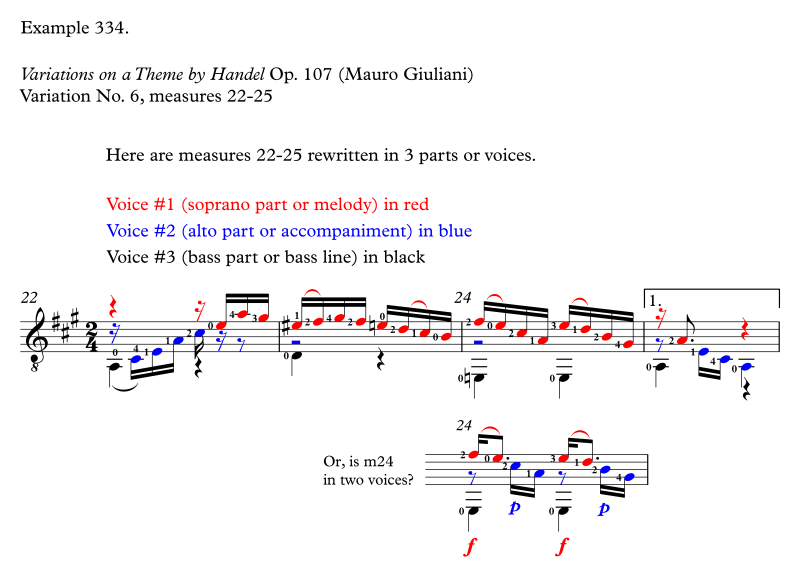

Measures 22-25 are similar to 18-21 with arpeggios and a scale. Here is the original notation. Example #333:

In my opinion, this passage is also in three voices. I say "in my opinion" because when it comes to hidden and implied voices, the answer is "in the ear of the beholder." Another guitarist may interpret the passage differently. For example, here are two interpretations of this passage. Example #334:

Listen to me play both versions in Video #75.

Video #75: Variations on a Theme by Handel (Mauro Giuliani), m22-25, played as three voices, two versions

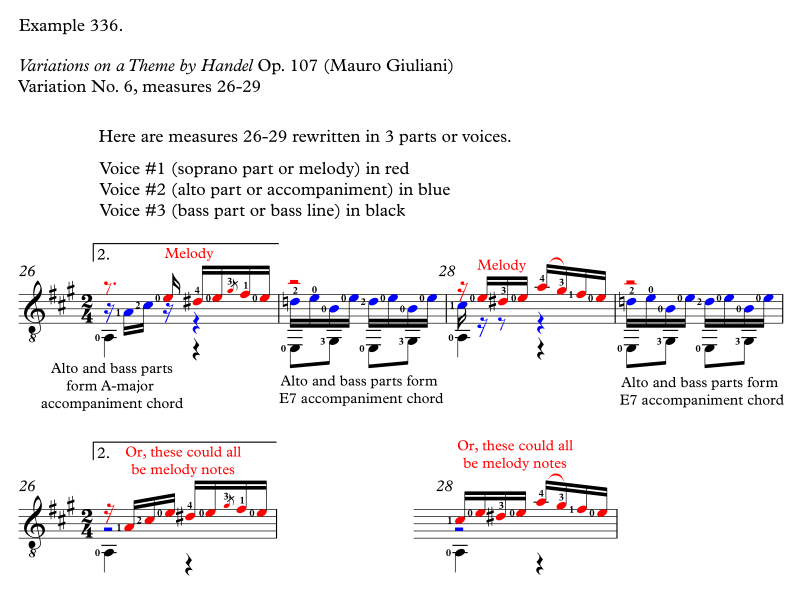

Going on, here is the original notation for measures 26-29. Example #335:

And here it is, as I hear it in three voices with two options for measures 26 and 28. Example #336:

Listen to me demonstrate the options in Video #76.

Video #76: Variations on a Theme by Handel (Mauro Giuliani), m26-29, played as three voices, two versions

It takes experience, critical listening, and sometimes some guesswork to find hidden or implied voices, whether in contrapuntal or non-contrapuntal music. But once you discover the multi-dimensionality of a passage, you can bring an otherwise mundane phrase to life.

It is essential to be aware of the voices in a passage and which notes belong to which voices in the early stages of learning a piece. Then, you can practice it with the correct balance between the parts and use dynamics, tone colors, and articulation to communicate that magic to your listeners.

SUMMARY

You learned that finding and practicing the individual voices of your music has these benefits:

- The most obvious benefit is that knowing which notes form the melody will help you practice playing those notes more prominently than those in subordinate voices. Usually, making the melody prominent is key to making a piece sound its best.

- If you can identify the voices in your music, you can use some advanced practice strategies in which you practice the voices separately to improve several elements of your playing.

- You can learn which notes form the accompaniment and practice it independently. That way, you can easily hear any flaws in your playing of the accompaniment and fix them. Practicing the accompaniment alone also increases your awareness of what the accompaniment sounds like by itself.

- If you know which voice is which, you can adjust the relative balance between two or more parts with great precision.

- Separating the music into its component voices allows you to see the independent rhythms of each part so that you hold the notes for their correct duration.

- Practicing the individual voices of a passage shines a spotlight on flaws in fingering and execution.

- Practicing the individual voices helps you choose whether to play a voice as a pure line (only one note ringing at a given moment) or allow notes to ring together.

- You can improve the tone quality of a voice.

- You can improve the clarity of the voices (eliminate buzzes and muted notes).

- In contrapuntal music, you can learn to hear the individual voices and how they interact. Then, you can apply practice tools to make those interactions crystal clear.

- An awareness of the voices of the music enables you to hear and appreciate the intricacies, uniqueness, creativity, and wonder of the composer or arranger's work. That awareness will permeate your playing, and your listeners will also sense and hear it.

- You can go even further by finding hidden or implied voices in both contrapuntal and non-contrapuntal music. When you differentiate these voices, you will give the piece the lifelike multi-dimensionality the composer intends it to have rather than a dull, colorless, one-dimensional sound.

DOWNLOADS

1. Download a PDF of the article with links to the videos and audio clips. Depending on your browser, it will download the PDF (but not open it), open it in a separate tab in your browser (you can save it from there), or open it immediately in your PDF app.

Download the PDF: HOW TO LEARN A PIECE (SONG) ON THE CLASSICAL GUITAR Part 11-C (with links to the videos and audio clips)

2. Download the videos. Click on the video link. After the video page opens, click on the three dots on the bottom right. Select "Download."

Video 60: Voices ringing together, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Video 61: Allowing open strings to ring in the soprano voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Video 62: Damping the open strings in the soprano-voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Video 63: Allowing open strings to ring in the bass voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Video 64: Damping the open strings in the bass voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Video 65: Damping the open strings on both voices, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Video 66: Play the accompaniment but sing the melody, Study No. 2 (Fernando Sor)

Video 67: Play the accompaniment but sing the melody, Study No. 5 (Fernando Sor)

Video 68: Sing the upper voice while playing the lower voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Video 69: Sing the bass voice while playing the upper voice, Bourrée (J.S. Bach), m1-8

Video 70: Prelude from Cello Suite No. 1 (J.S. Bach), m1-4, played in three voices

Video 71: Prelude from Cello Suite No. 1 (J.S. Bach), m22-24, played in three voices

Video 72: Variations on a Theme by Handel (Mauro Giuliani), m10-17, one-dimensional interpretation

Video 73: Variations on a Theme by Handel (Mauro Giuliani), m10-17, played as three voices

Video 74: Variations on a Theme by Handel (Mauro Giuliani), m18-21, played as three voices

Video 75: Variations on a Theme by Handel (Mauro Giuliani), m22-25, played as three voices, two versions

Video 76: Variations on a Theme by Handel (Mauro Giuliani), m26-29, played as three voices, two versions